- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- Fit-for-55 in France: what are the mediu...

Post No. 426. Long-run benefits of transition policies are clear and well-documented in the literature, which shows huge economic losses in case of inaction. These policies also have medium-run consequences, which we study here. We use a new approach to model the impact on the French economy of a carbon tax in line with the CO2 emission reduction of Fit-for-55. Under the conservative assumption that there are no new clean technologies along the transition, we find that the long-term benefits of reducing carbon emissions implies some macro costs during the transition. In the short run, with unchanged monetary policy, inflation increases slightly due to the direct transmission of carbon taxes to prices. In the medium run, we find slower output growth, mainly driven by large real supply effects.

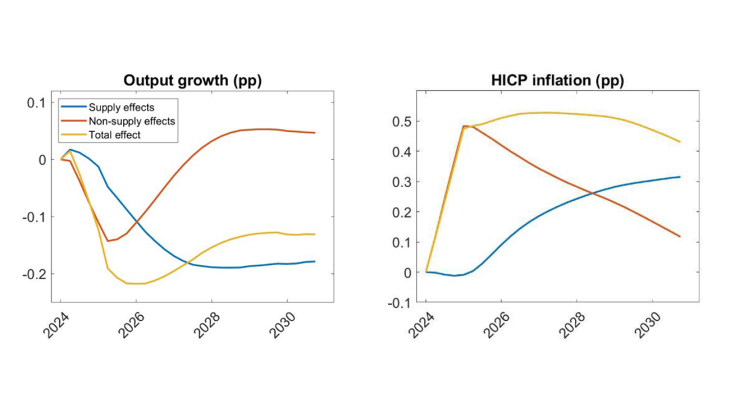

Figure 1: Output and inflation response to the Fit-for-55 carbon tax shock

Source: Henriet, Kalantzis, Lemoine, Lisack & Turunen (2025).

As the urgency of climate change grows, so does the need to understand the macroeconomic impact of ambitious decarbonization policies. The long-run motivation of these transition policies is clear and well-documented in the literature: inaction would notably imply huge economic losses in the long run. For example, according to scénarios à long terme du NGFS, under current policies, global emissions would stay around 40 Gt CO2/year, global temperature, already 1.5 °C above pre-industrial level, would reach 3 °C in 2100 and global GDP would decrease by around 30% at this horizon. Scenarios implementing transition policies, by reaching net zero emissions in 2050, would allow to keep the temperature increase around 1.5 °C by 2100 and, hence, to avoid most of the GDP loss. Moreover, we can already see the impact of physical risks in observed data: the relative price of insurance and losses due to extreme events show increasing trends in recent decades (Bénassy-Quéré, 2025).

However, as pointed out by Pisani-Ferry (2021), transition policies should also have macro costs in the short and medium run . In Henriet et al. (2025) we combine two models that capture both structural and short-term dynamics and apply them to assess the medium run macroeconomic effects of the part of the Fit-for-55 package related to carbon prices in France. The European Union’s Fit-for-55 package sets out to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. For France—where emissions have already declined by about 25%—this implies a further 30pp cut within just a few years. Such a transition would entail a major reallocation of capital, labour, and energy use that we analyse with our new approach.

Combining a pair of models for assessing short- and medium-run impacts of the Fit-for-55 package

We develop a hybrid modelling strategy to assess how the Fit-for-55 package affects the French economy by 2030. Our set-up combines two tools: (1) FR-GREEN, a new real dynamic general equilibrium model that captures the structural changes induced by the energy transition; and (2) FR-BDF, our usual nominal forecasting model that accounts for the short-term dynamics of inflation and demand. FR-GREEN models the shift from fossil-based to low-emission technologies, accounting for investment irreversibility and different production processes across sectors. This combined approach provides a more complete picture than using either model alone and seems to us better suited for policy analysis than environmental versions of large-scale structural models. In the short run, it benefits from the better empirical fit and the detailed accounting framework of FR-BDF compared to such models and in the medium run, it incorporates the key supply effects of the transition thanks to inputs from FR-GREEN.

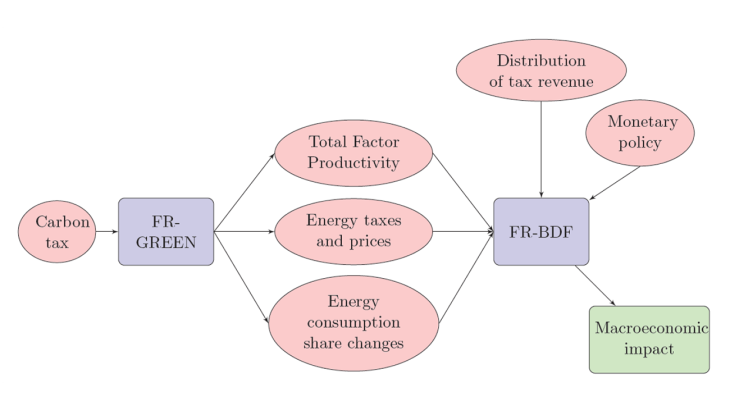

Figure 2: Interacting FR-GREEN and FR-BDF to simulate the impact of climate policy.

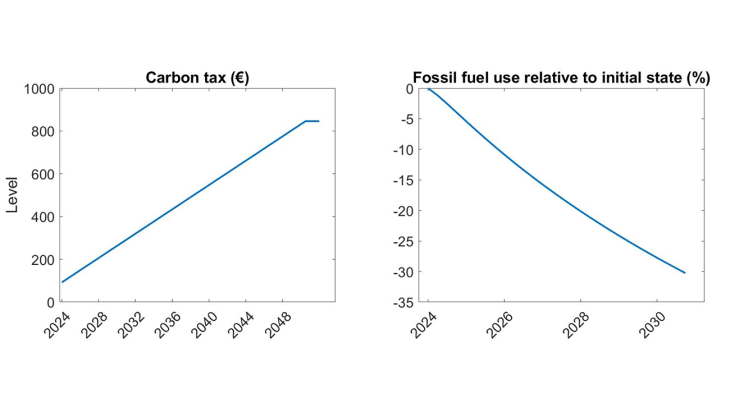

We implement this strategy in two steps (see Figure 2), under the conservative assumption that there is no green technological innovation during the transition. First, we model the Fit-for-55 package within FR-GREEN as a gradually increasing carbon tax, which induces a 30% reduction in fossil fuel use (oil and gas), and hence emissions, by 2030 (see Figure 3). The carbon tax reaches around €275 per tCO2e in 2030, which is higher than the €150 per tCO2e level roughly reached at this horizon in the “Highway to Paris” scenario of NGFS (2025), reflecting our more conservative assumption that there are no new clean technologies along the transition. We further assume that the tax increase continues linearly until 2050, to reflect the additional net zero objective of the European Commission at this extended horizon. These carbon tax policies are assumed to be identical across all euro area countries, implying a neutral impact on the competitiveness of the French economy with respect to the rest of the euro area. Second, the outputs of FR-GREEN are fed into FR-BDF as shocks to energy prices, the efficiency of labour and capital, and the share of fossil fuel energy within consumption prices. In these simulations, other economic policies remain neutral: on the fiscal side, the government budget balance is unaffected as carbon tax revenues are assumed to be fully rebated to households and firms, while on the monetary side, the nominal interest rate moves one-to-one with inflation to maintain an unchanged real interest rate.

Figure 3: Carbon tax path (left panel) and fossil fuel use (right panel) in FR-GREEN.

Source: Henriet, Kalantzis, Lemoine, Lisack & Turunen (2025)

Reaping the long-term benefits of decarbonation requires paying macroeconomic transition costs

Our main finding is that the transition to a low-carbon economy implies macroeconomic costs in the medium run. Relative to a no-transition baseline scenario, we estimate that output growth would be 0.2 percentage point (pp) lower at the trough and obtain a peak inflationary effect of 0.5pp (see Figure 1). These effects are primarily due to the shift from efficient but polluting to less efficient but clean technologies, which entails a substantial loss in the average efficiency of capital and labour. The direct effect of the tax and the induced productivity decline drive price increases, despite some downward pressure from the recessionary effect of the implied loss in real income. In the short run, consumer prices increase because of the carbon tax, with an adverse impact on demand despite the redistribution of tax receipts, while the medium-run inflationary effect as well as the output losses arise mainly from supply-side effects. While FR-BDF would be sufficient on its own in the short run for capturing effects stemming mainly from non-supply effects, most of the total medium-run impact on output and inflation is due to the supply effects extracted from FR-GREEN.

Which monetary policy to stabilize inflation in the medium run?

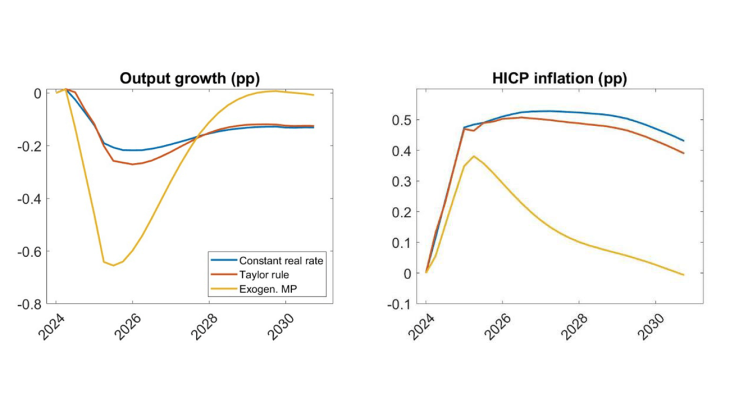

Monetary policy plays a critical role in shaping how the economy responds to any shock, and this is also true for the energy transition. The baseline scenario assumes a constant stance of monetary policy: the nominal interest rate is adjusted to keep the real rate constant, allowing inflation to rise temporarily. Alternative policies reveal a trade-off. Increasing interest rate according to a standard Taylor-rule reduces inflation somewhat but leads to deeper output losses. A more aggressive policy—raising interest rates by 200 basis points—brings inflation back to the 2% target in the medium term, corresponding to the ECB’s primary mandate of price stability, but amplifies the slowdown of GDP growth (see Figure 4). Note that the size of the required monetary policy tightening could be smaller in other macro models, which show a stronger sensitivity of inflation to to interest rates.We should also keep in mind that a surplus of inflation by 0.5pp should be manageable, as it was the case in the early 2000s: over 1999-2007, energy contributed by 0.4pp to an average HICP inflation of 2.1% in the euro area.

Figure 4: Output and inflation response to carbon tax shocks, under different monetary policy assumptions

Source: Henriet, Kalantzis, Lemoine, Lisack & Turunen (2025).

Caveats

Since the two models combined in this analysis do not include technological innovation, the results shown here should be considered an upper bound of the effect on inflation and output loss. However, additional inflationary effects could also stem from increased shortages in critical materials for electrification (e.g. rare earths or metals used for batteries). The absence of assessment of climate damages also prevents an analysis of the trade-offs between the medium-run costs of transition policies and their long-run benefits, which arise from the reduction of physical risks.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 29th of January 2026