The Banque de France – repository and creator of objects that bear witness to the past

As the custodian of France's gold, but also of priceless artistic treasures, the Banque de France has acquired important collections over the course of its history, which it displays to the public during the Heritage Days or as part of special exhibitions. The Banque de France strives to put its role as a curator and creator of historical objects at the service of connoisseurs, enthusiasts and the general public.

The Banque de France – a banknote specialist for over 200 years

Banknotes first appeared in the 18th century as a major financial innovation and became increasingly widespread over time. From its inception, the Banque de France supported this trend by designing, manufacturing and issuing more than 100 types of franc banknotes. Today, the Bank is the leading producer of euro banknotes in the Eurosystem and provides its expertise to other countries.

The "Saint-Exupéry" – the last FRF 50 banknote issued by the Banque de France

The “Saint-Ex” is emblematic of the last range of banknotes to be designed before the introduction of the euro. It was intended to be practical and modern, featuring the famous aviator and writer in a predominantly blue colour.

The "Foch" – a FRF 100,000 banknote that was never issued

Faced with the risk of inflationary pressures, in 1955 the Banque de France decided to produce a banknote with an exceptional value of FRF 100,000. The project was ultimately abandoned due to the decision at the end of 1958 to change over to the new franc.

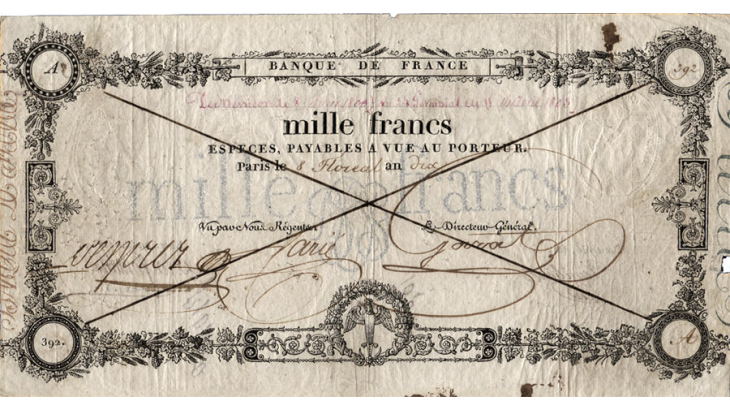

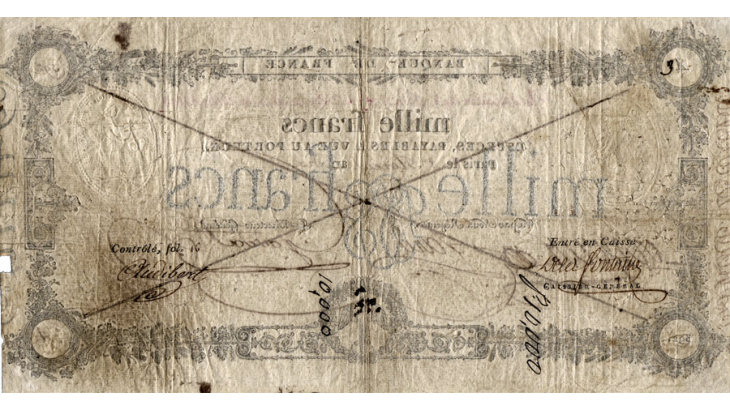

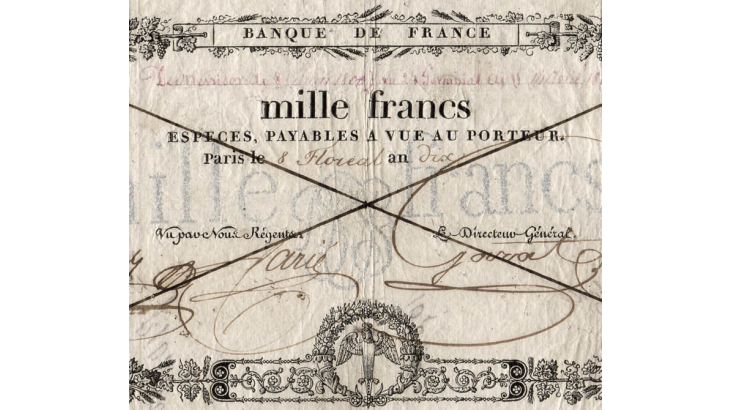

First banknotes for commercial and industrial payments

The first Banque de France banknotes were issued in June-July 1800, in two denominations: FRF 500 and FRF 1,000. Their high values meant that were used only by major merchants and industrialists.

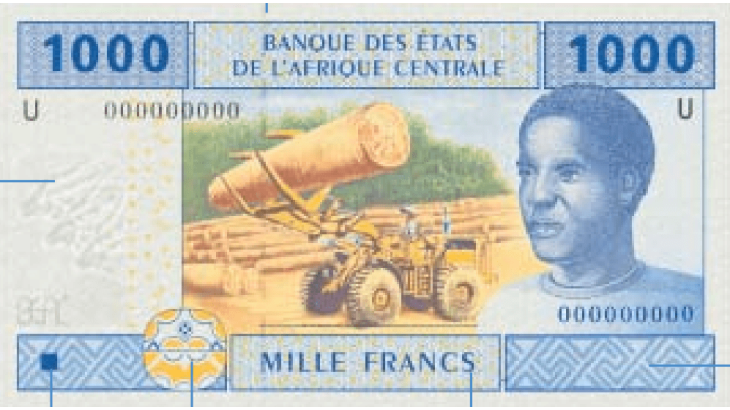

Banknotes – the Banque de France exports its know-how

The Banque de France designs banknotes for other central banks. Depending on requirements, its involvement ranges from the production of mock-ups to the actual printing of the final banknotes. It notably supplies the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) and the Bank of Central African States (BEAC).

Coin collection

The Banque de France’s numismatic collection is almost 150 years old and traces 25 centuries of history. It comprises nearly 30,000 coins, tokens and medals, and its remarkable pieces are regularly exhibited.

Cyrus the Great – Croeseid-type hemistater (between 554 and 529 BC)

This silver coin is one of the oldest in the Banque de France's collection. Cyrus the Great was the founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. He defeated the King of Lydia, Croesus, who had minted one of the oldest coins known to date, the Croeseid.

Aes Signatum – one of the first Roman coins (274 BC)

The first Roman coins took the form of bronze ingots. They often bore warlike motifs (shields, swords) or economic ones (pigs, oxen). At the time, there were no coins, so the ingot was split to make up for their absence.

Athens – tetradrachm (ca. 460 BC)

The Greek cities minted coins as early as the 6th century BC. These independent cities adopted a particular and varied coinage that recalled their patron deity, as illustrated by this silver coin bearing the image of Athena's owl.

Jean Le Bon (the Good) – the franc à cheval (1360)

This was the first appearance of the franc: the coin was intended to pay the ransom of the king, who had been taken prisoner by the English. The choice of the word franc was thus a political gesture responding to the need for national affirmation that arose during the Hundred Years' War.

The franc germinal (year XI)

With the creation of the franc germinal in 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte, the First Consul, assigned a fixed weight of silver and gold to the currency, thereby guaranteeing the consistency of commercial transactions. It became a European benchmark for several decades.

Art and furniture collection

Distributed among the magnificent state rooms of the Hôtel de Toulouse and the Galerie Dorée, the Banque de France's collections of paintings and furniture are the fruit of a remarkable policy of acquiring paintings, furniture, tapestries and objets d'art that has been pursued to this day. These pieces bear witness to the golden age of French decorative arts.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Fête at Saint-Cloud

A highlight of the Banque de France's collections, this painting is one of the artist's masterpieces, with its harmonies of green and gold enhanced by a few hints of red. A shroud of mystery surrounds the origin of this work, whose name does not appear anywhere before 1862.

The two paintings by Boucher (1755)

Inspired by Torquato Tasso's Aminta, these paintings are part of a set of four commissioned by Madame de Pompadour for her château at Crécy, which was bought in 1757 by the son of the Count of Toulouse.

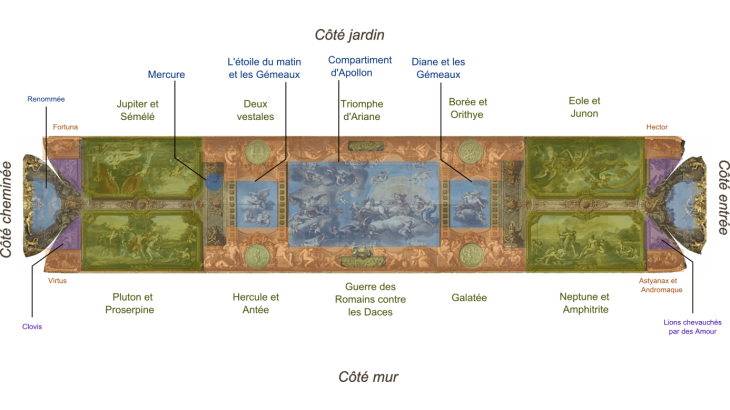

The vaulted ceiling of the Galerie Dorée

Painted as a fresco by François Perrier between 1646 and 1649, it was faithfully copied in the 19th century following its deterioration. At the centre, in all its majesty, is the chariot of Apollo preceded by the morning star and followed by the Moon crossing the sky. In the four corners are the four elements.

The 17th century Italian paintings

Bought by Louis Phélypeaux de la Vrillière to adorn the original Golden Gallery, these are masterpieces of the modern Roman school. Seized during the Revolution, the original paintings are now in the Louvre and other national museums.

The barometer and thermometer (ca. 1720)

Decorated with gilt-bronze motifs featuring lobsters, anchors and the blowing wind, these marquetry pieces are the work of the cabinetmaker André-Charles Boulle and Gilles-Marie Oppenord.

Gold wood carvings

The renovation work on the Galerie Dorée was commissioned by the Count of Toulouse in 1715 and entrusted to the King’s architect, Robert de Cotte (1656-1735). The new wood carvings were the work of the King’s sculptor, François Antoine Vassé (1681-1736), and incorporate marine and hunting imagery to reflect the Count of Toulouse’s titles of Grand Admiral and Grand Veneur. Two sculpted groups adorn the opposite ends of the gallery: Diana, goddess of hunting, is displayed above the door, while Aeneas appears at the opposite end, above the chimney, accompanied by Venus and Eurus, the wind of storm. The marine carvings were inspired by the Triomphes marins tapestries offered by Madame de Montespan to her son the Count of Toulouse. The ten paintings from the collection of Louis Phélypeaux de la Vrillière were also embedded in the wood carvings, in a slightly different order. The light from the large windows is reflected in six mirrors installed symmetrically opposite.

Updated on the 12th of January 2024