Non-Technical Summary

Our understanding of how monetary policy affects the economy hinges on the accurate measurement of exogenous monetary policy shocks and their impact on GDP and inflation. This generated a whole literature to identify exogenous monetary policy shocks, through different methods, either quantitative or qualitative, e.g. Romer and Romer (2004) based on Federal Reserve's internal forecasts and narrative records from the reading of transcripts of FOMC meetings.

These shocks are a cornerstone of empirical research in macroeconomics. They underpin studies of how central banks influence the economy, guide policy evaluation, and inform the design of economic models. The usefulness of these shocks rests on a simple but critical requirement: they must capture only unexpected and exogenous changes in policy, free from other macroeconomic influences.

This paper shows that a key assumption behind conventional identification strategies—the idea that systematic monetary policy, or the policy rule, is constant over time—is problematic. If, in reality, the rule changes—due to shifts in policymakers’ preferences or other factors—these systematic changes are embedded in the estimated shocks. As a result, the shocks are contaminated by other macroeconomic influences, biasing the estimated impulse responses of how monetary policy shocks affects the economy.

Our theoretical framework shows that in the presence of time-varying systematic policy, conventional shocks are predictable from interactions between the policy rule’s inputs and measures of the policy rule’s variation. Empirically, we operationalize this prediction by measuring fluctuations in U.S. systematic monetary policy using the “hawk–dove” composition of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), following Istrefi (2019). Hawks are relatively more concerned about inflation, while doves place greater emphasis on employment and growth. Our focus is the identification of monetary policy shocks as in Romer and Romer (2004) (RR). The RR shocks are the estimated residuals of a Taylor rule-type regression with constant coefficients on its inputs, such as forecasts for inflation and unemployment. We show that RR shocks are significantly predictable from the FOMC hawk–dove balance interacted with Taylor-rule inputs. Across different samples—1969–1996, 1969–2007, and the post-Volcker disinflation period 1983–2007—the explanatory power ranges from 10% to 54%.

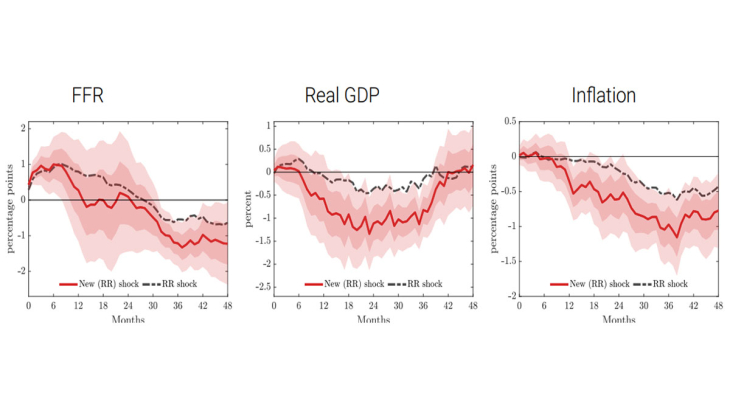

Motivated by this evidence, we propose new shock series that are orthogonal to measured fluctuations in systematic monetary policy. The new shocks differ substantially from the originals, with a correlation of 0.67 and many instances of sign reversals. They also display lower dispersion. Comparing impulse responses over the post-1983 period, we find that the new monetary policy shocks generate less persistent Federal Funds Rate (FFR) movements but substantially larger and quicker declines in real GDP and inflation (see Figure 1). The differences from the original RR shocks are statistically significant at many horizons, suggesting that removing the influence of time-varying systematic policy yields a more accurate assessment of the effects of monetary policy in the U.S.

Keywords: Monetary Policy Shocks, Systematic Monetary Policy, Identification.

Codes JEL: E32, E43, E52, E58.