Post No. 435. Europe’s venture capital market is growing but remains much smaller than in the United States, holding back innovation. The gap is partly due to a lack of appetite among private European investors. A more integrated ecosystem, pan-European funds and measures to facilitate institutional investors’ access to venture capital are all key to boosting start-up financing.

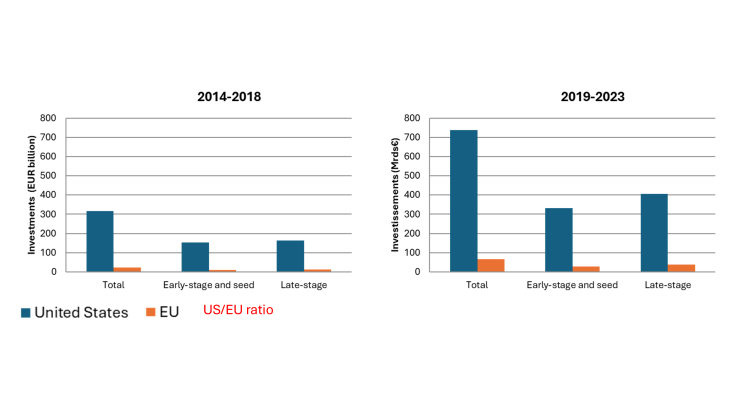

Chart 1. Amounts invested in venture capital in the European Union and the United States

The European venture capital market remains insufficiently developed despite recent progress

Although the market has slowed in the past two years – after expanding sharply from 2020 to 2022 – annual venture capital (VC) investment has grown significantly in the European Union (EU) since 2010, from EUR 2.5 billion to over EUR 10 billion in 2023.

However, Europe’s VC market still lags behind that of the United States. Between 2014 and 2023, VC investment amounted to EUR 89 billion in the EU, compared with over EUR 1,000 billion in the United States, and the gap has since only narrowed marginally. The disparity is affecting all stages of start-up financing. The shortage of large-scale European funds is limiting access to late-stage financing (see Julien-Vauzelle et al., 2022), while there are also persistent difficulties in early-stage financing and especially seed financing (Chart 1).

Yet the VC industry plays a crucial role in fostering innovation as it supports the emergence and growth of promising young firms. VC investors are more willing to accept risks and commit to a long-term investment horizon, making them particularly suited to financing start-ups. Indeed, the Draghi report (2024) identified Europe’s lag in the VC segment as one of the reasons for its growing technology and productivity gap with the United States.

The key role of the public sector and lack of appetite among European institutional investors

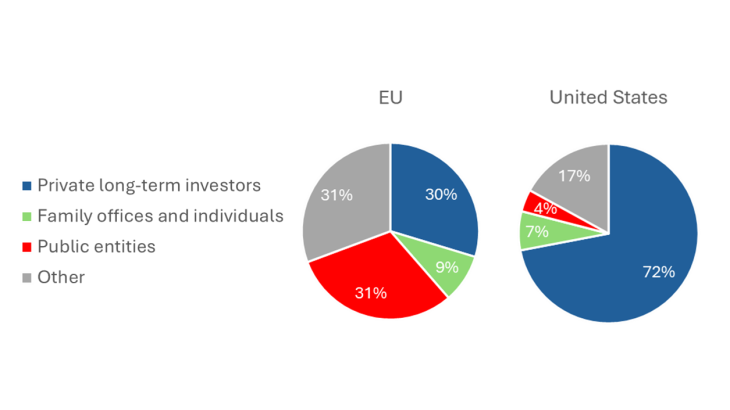

Public intervention is useful for addressing market failures, notably when private investors have a shorter investment horizon than the time needed for firms to mature. In Europe, a mix of national and European public instruments (such as Bpifrance, or KfW in Germany, alongside the European Investment Fund or EIF, and the European Tech Champions Initiative or ETCI) are helping to expand the VC ecosystem by increasing the supply of financing. Between 2013 and 2023, public entities in Europe and the United States invested comparable amounts in VC – around EUR 40 billion respectively (Arnold et al., 2024); however, in Europe they accounted for 30% of investors, while in the United States they accounted for 4%. Thus, the relative weakness of European VC financing can mainly be explained by a lack of long-term private financial investors, as they contribute 17 times less than in the United States (Chart 2).

Developing Europe’s VC market implies expanding and diversifying the pool of private investors. In the United States, pension funds and university endowment funds are major contributors to the segment, but their presence in Europe is more limited. European institutional investors, especially insurers, traditionally favour fixed income products. In the fourth quarter of 2024, European insurers held just 1.45% of their investments in private equity (which is a broader category than venture capital as it includes equity investments in unlisted firms to finance their growth, transformation and expansion). Yet their ability to invest over the long term and spread their risk means they are well-placed to play a bigger role in VC financing. The revision of the Solvency II directive has removed some barriers to VC investment insurers by facilitating access to the Long-Term Equity Investment (LTEI) mechanism.

Chart 2. Breakdown of investors from 2013 to 2023 (% of total venture capital raised)

Developing the European VC ecosystem will require combined efforts

On the supply side, Europe’s smaller VC investor base mainly reflects savers’ preference for liquid and secure investments. In line with this, institutional investors prefer to offer their clients diversified funds with a strong performance track record, and that are capable of absorbing large investments without breaching concentration limits. However, the fragmentation of European financial markets can limit the emergence of sufficiently large and diversified funds.

VC funds also have difficulty exiting their positions, especially their stakes in start-ups. They can either sell them to other funds or firms, or carry out an initial public offering (IPO) – although the latter option is less common in the EU (Chart 3). This lack of exit strategies weighs on VC funds’ performances, thereby reducing the incentive to finance innovation. Yet IPOs increase firms’ profitability, employment levels and capacity for innovation (Böninghausen et al., 2025). Consequently, it is essential to foster the emergence of pan-European funds capable of scaling up innovative start-ups, and to develop a unified and liquid listed market over the long term that includes SMEs. Such a market would be a powerful, albeit ambitious, tool for removing barriers to innovation financing.

On the demand side, the situation is affecting European start-ups as they frequently choose to raise financing from foreign and especially American VC funds. The appeal of these funds lies not just in their large financing capacity, but also in the strength of their ecosystem with its extensive network effects.

In addition to these financial levers, nurturing innovative firms also implies speeding up the journey from scientific research into entrepreneurship and financial education – both of which are essential for increasing the number of high-potential projects. Similarly, a dedicated, common regulatory and tax framework, such as the European Commission’s proposed 28th regime, would provide EU start-ups with harmonised rules and allow them to benefit fully from the single market.

Chart 3. Change in the breakdown of venture capital exits, in amount

Public initiatives to facilitate EU institutional investors’ access to venture capital

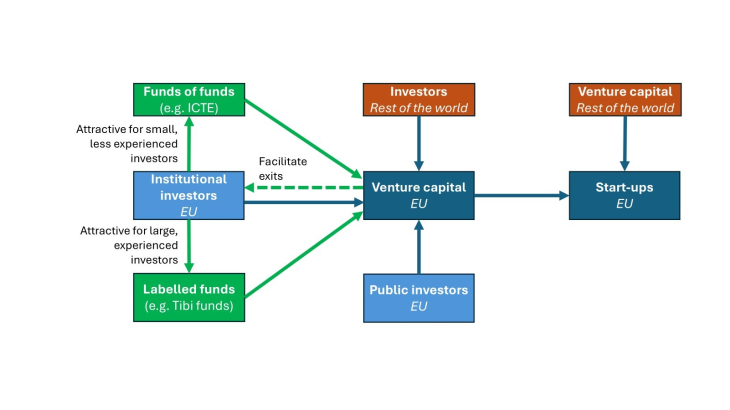

There are several avenues worth exploring to attract more private institutional investors to the VC segment. European funds of funds – such as the ETCI 2.0 to be launched in 2026 by the EIF – allow institutional investors without the necessary in-house expertise to access diversified investments at reduced management costs (see diagram below). However, they hold limited appeal for large institutions, which prefer investing directly in VC. The European Commission’s planned launch of a voluntary European Innovation Investment Pact – a European version of France’s Tibi initiative – would provide an interesting alternative: it would foster the emergence of larger, EU-wide funds and reduce the domestic bias in national initiatives, while still giving investors the freedom to choose which VC funds they invest in (see diagram below). Alongside this, the Commission is planning to revise the European Venture Capital (EuVECA) label for VC funds in 2026, which could make it easier to raise larger amounts of funds across borders by increasing the pool of eligible assets and strategies.

Diagram: Avenues for improving start-up financing in the EU

Download the full publication

Updated on the 18th of February 2026