Non-Technical Summary

Disruptions to global supply chains have become a major concern for policymakers since the Covid-19 pandemic. When deliveries are delayed or key inputs are missing, firms may slow production, lay off workers, or raise prices. Understanding how supply-chain tensions affect economic activity, employment and prices is therefore essential for the conduct of stabilization policies such as fiscal and monetary policy. This paper shows that two sources of supply-chain tensions, that are often bundled together in public debate, have distinct macroeconomic effects. The first is a transportation shock, reflecting sudden capacity losses or bottlenecks in shipping and logistics that make it harder and more expensive to move goods. The second is an input-production shock, arising from disruptions in the production of highly specific intermediate goods that firms cannot easily substitute in the short run. Both types of shocks can lengthen supplier delivery times and slow global output, but they operate through different channels.

To distinguish these shocks in the data, we use monthly global indicators of real transportation-costs, supplier delivery times, and world industrial production. The key idea is intuitive. When transportation capacity is constrained, shipping prices rise. When the production of specific inputs is disrupted, global output falls and demand for transport services declines, causing transportation prices to fall even as delivery times lengthen. We also use well-documented events – such as disasters, port closures, and maritime canal blockages – to help identify periods of severe supply chain tensions, and by bringing other information we obtain from economic theory to the empirical setup.

The estimated shocks display clear historical patterns. Transportation shocks cluster in periods of tight logistics capacity and line up with large, discrete events, such as the Suez Canal blockade in 2021 and shipping disruptions linked to the Panama Canal drought. Input-production shocks are more episodic and less clustered, with prominent spikes around major input shortage and the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Both shocks are contracting economic activity and raising prices. However, their persistence differs markedly. Transportation shocks raise shipping costs and producer prices mainly in the short run and fade within two years. Input-production shocks generate larger and more persistent output losses and a longer-lasting increase in producer prices, with a gradual pass-through to consumer prices and core inflation. This reflects the difficulty of replacing missing, highly specific inputs within complex production networks.

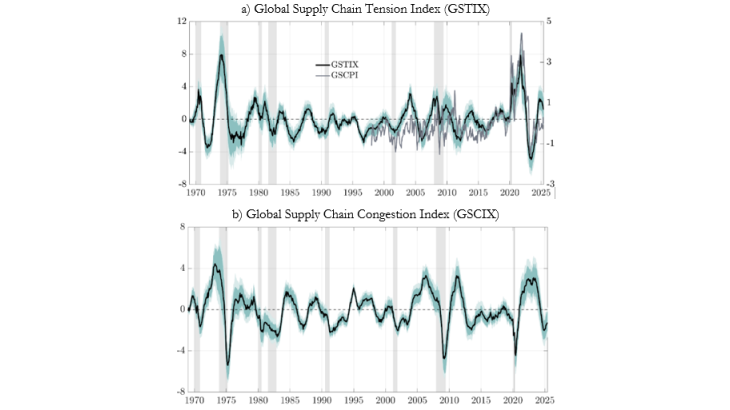

A central contribution of the paper is the development of practical monitoring tools. We construct a Global Supply Chain Tension Index (GSTIX) that summarizes, month by month, supply chain tensions stemming from transportation and input-production shocks (Figure 1a). The index can be decomposed into these two components, allowing policymakers to identify the source of supply-chain stress. We also build a separate index capturing demand-driven congestion, labeled as Global Supply Chain Congestion Index (GSCIX), helping to distinguish supply-side tensions from strong global demand (Figure 1b).

The paper also examines how these global supply shocks affect the U.S. economy and the response of monetary policy. Both shocks reduce industrial production, raise unemployment, and affect inventories. Transportation shocks lead to a sharp but temporary rise in producer prices, with limited spillovers to consumer price inflation. Input-production shocks cause a deeper and more persistent downturn and more sustained inflationary pressures. A key finding is that the U.S. interest rates respond differently across shocks. Transportation shocks are largely looked through, while input-production shocks are followed by a clearer and more persistent tightening, consistent with their longer lasting inflationary effects. Monetary policy partly accommodates the inflation response to limit the output losses.

Keywords: Supply Chains, Input Shortages, Transport Shocks, Structural Vector Autoregressions, Inflation, Monetary Policy, Demand-Induced Congestion.

Codes JEL: C32, E31, E52, F60, R40.