Post No. 428. In France, the 2009 reform of the judicial map profoundly reshaped the territorial distribution of commercial courts. Despite initial fears, court mergers have not undermined the commercial justice system; on the contrary, we show that they have improved the quality of decisions by reducing certain errors of judgment in the handling of insolvencies for companies with fewer than 10 employees.

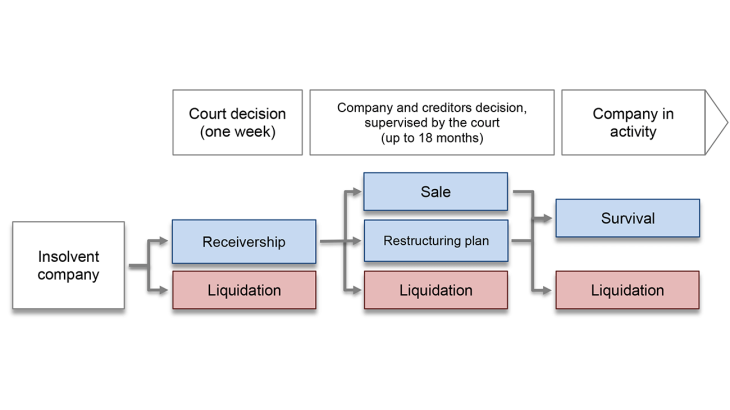

Chart 1: French bankruptcy process

In 2008-09, France's judicial map underwent a major overhaul with court mergers. Like other European countries (Italy, the Netherlands, etc.), France was seeking to modernise its commercial justice system, reduce costs, and improve the quality of decisions rendered.

The number of commercial courts in metropolitan France has dropped from 185 to 134. Some were merged with courts in the same department, while others were newly created. The decision to merge courts was not based on their performance: the smallest courts were closed almost automatically, and their jurisdiction was transferred to larger courts. This reform raised many concerns: geographical distance for litigants, overloading of the absorbing courts and, ultimately, a risk of undermining commercial justice.

French commercial courts are special courts: they are composed of non-professional judges, elected from among business leaders, who serve on a part-time basis. This composition, which is deeply rooted in the local community, can lead to decision-making biases (due to the lack of anonymity, the proximity between the elected judges and the business leaders who elect them, and local social pressure to avoid business closures). However, it has the advantage of having judges with a good understanding of the local context. In collective proceedings, the court decides whether to liquidate the company or attempt to restructure it (Chart 1). Epaulard and Zapha (2022) showed that the court plays a major role in choosing the proceedings, a decision which has a significant impact on the business' survival.

Two errors of judgment are possible: (1) attempting to save a business that has little or no chance of survival – what economists call “continuation bias”; (2) liquidating a business that could have survived – the “liquidation bias.”

Epaulard and Zapha (2025) assess the impact of the 2009 reform on the effectiveness of the courts in dealing with companies in difficulty, and more specifically on the continuation and liquidation biases. The impact of the reform on the other areas of commercial justice (in particular the handling of disputes between companies) is not examined here.

The analysis is based on a near-exhaustive sample of 600,000 bankruptcy proceedings opened in France between 2000 and 2019, taken from the Banque de France's FIBEN database. The econometric method used is the “difference-in-differences” method, which compares the evolution of judgments in areas where a court has been absorbed or has absorbed another court with that of areas that have remained unchanged. The analysis takes into account the characteristics of the businesses (size, sector, local economic conditions) and the economic situation (as the reform was implemented in 2009 at the time of the financial crisis).

The reform reduced the continuation bias without changing the liquidation bias

The results are clear: the reform reduced the continuation bias, i.e., the tendency to grant non-viable companies a second chance, without increasing the liquidation bias. In other words, the merged courts are more selective: they restructure less often, but the restructurings are more successful. Overall, following the reform, the chances of survival for truly viable companies remain unchanged or slightly higher.

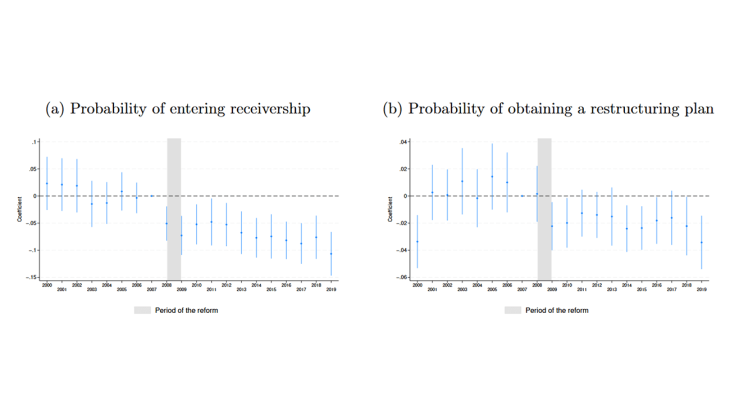

Chart 2: The reform’s impact for companies in the absorbed jurisdictions

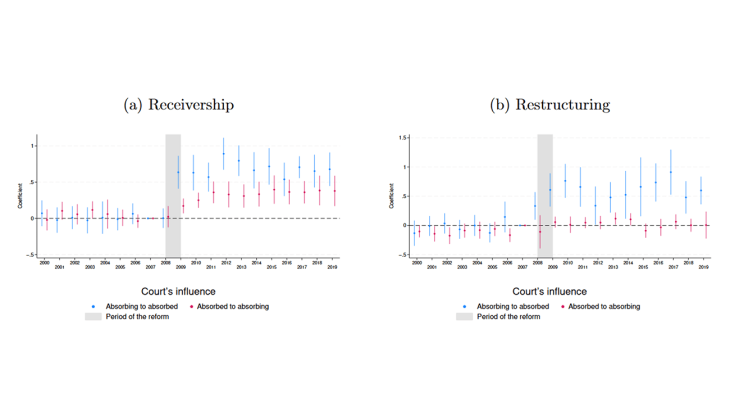

In concrete terms, in the jurisdictions absorbed, the probability of being placed in receivership by the judge fell by an average of 6 percentage points (Chart 2, left panel) and the probability of obtaining a restructuring plan within 18 months of the judge's initial decision fell by 2 percentage points (Chart 2, right panel). The survival rate of restructured companies did not deteriorate; on the contrary, the probability of survival seven years after receivership increased. The change was immediate after 2009 and has been lasting: local decision-making biases seem to have rapidly disappeared in favour of the practices of the absorbing courts. Courts’ behaviour, measured by their average receivership rate (Chart 3, left panel) and restructuring rate (Chart 3, right panel), is passed on between absorbed and absorbing courts. We observe that the influence of absorbing courts on the receivership and restructuring of companies (in blue) is much greater than that of absorbed courts (in red). Up to 75% of the chances of receivership and restructuring are attributable to the influence of absorbing courts after the reform, compared to 0% to 25% that are explained by the influence of absorbed courts.

Chart 3: The absorbing courts pass on their behaviour to the absorbed courts

The positive effect concerns almost exclusively the handling of bankruptcies of companies with fewer than ten employees (i.e., more than 90% of the bankruptcies studied). For larger companies, no impact is observed – probably because decisions concerning them were less prone to bias before the reform.

In addition, courts that absorbed another court do not appear to have been destabilised. Despite the increase in their workload (on average +50%), neither the length of procedures nor the quality of decisions deteriorated.

A successful reform that holds lessons for public authorities

From the point of view of public authorities, these results are positive. Contrary to initial fears, the merger of small commercial courts has neither impaired access to justice nor congested courts. On the contrary, it has improved the overall quality of decisions: courts are better able to distinguish between viable and non-viable companies and prevent unnecessarily prolonging non-viable activities.

The study emphasises that this success is not so much due to the size of the courts as to the efficiency of the absorbing courts: their practices have spread to companies from the absorbed courts. The key factor is therefore not consolidation per se, but the spread of best judicial practices. These results suggest that judicial rationalisation policies can produce real efficiency gains, provided that the merged courts rely on the practices of the best-performing entities rather than simply seeking to reduce costs.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 20th of January 2026