Non-Technical Summary

Recent developments in the global economy have led to unprecedented decisions by the largest oil producing countries. In April 2020, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United States jointly cut production by 9.7 million barrels per day (bpd) to counter the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. By mid-2021, a strong recovery in global demand led the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to ease earlier cuts by 2 million bpd. But in 2022, Russia, the world's largest oil exporter to global markets, caused supply disruptions in the oil market following its invasion of Ukraine. Later that year, OPEC reversed its stance and announced oil supply cuts of 2 million bpd for all of 2023, which were increased to 3.66 million bpd in April 2023, or about 3.7% of global demand. More recently, to support prices, OPEC and its partners (OPEC+) decided to extend oil cuts through 2024, and Saudi Arabia and Russia unilaterally cut oil production by an additional 1.3 to 1.5 million bpd until the end of December. From a policy perspective, these large oil supply cuts and easings pose new challenges for stabilization policies, motivating a renewed interest in understanding the transmission of oil supply shocks to promote better-informed policy decisions.

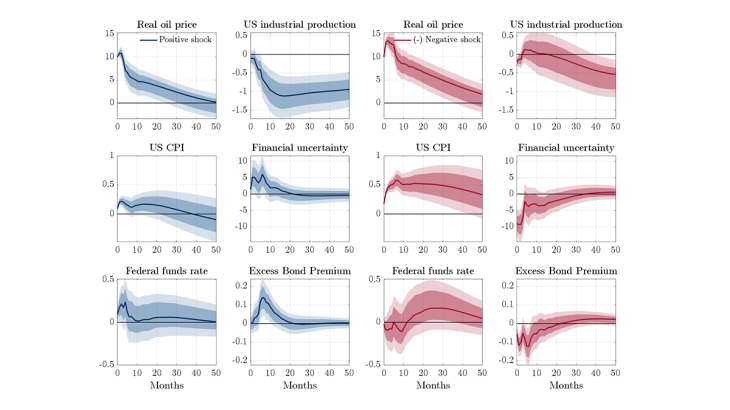

This paper explores the question of whether the impact of oil supply news shocks on U.S. output and prices depends on the sign of the shock. To investigate potential asymmetries, we use the nonlinear Proxy-SVAR approach developed by Debortoli et al. (2023) and identify an oil supply news shock using the series of surprise changes in oil future prices around OPEC announcements provided by Känzig (2021). We find that the transmission of oil supply news shocks is asymmetric. A shock raising oil prices produces a large and immediate decline in real activity and a small increase in prices. On the other hand, a shock reducing oil prices has a modest effect on real activity and a large effect on prices. We rationalize the asymmetric transmission of oil supply news shocks in view of two channels. The first is related to uncertainty, which includes a “real option” and a “risk premium” effect. According to this channel, an oil supply shock, regardless of its sign, increases uncertainty, which contributes to depress economic activity. This channel therefore operates by amplifying the negative real effects of unexpected oil price increases and dampening the positive real effects of unexpected oil price decreases. The opposite holds for prices. The second channel is related to the systematic response of monetary policy. As discussed by Bernanke, Gertler, and Watson (1997), the endogenous response of the central bank may account for a large portion of the recessionary effects of oil price shocks, and monetary policy may adopt an asymmetric reaction to such shocks. However, we find little role for this mechanism. This confirms that, in principle, monetary policy should not respond to supply shocks unless there is a risk of dis-anchoring of inflation expectations.

Keywords: Oil Supply News, Nonlinear Proxy-SVAR, Asymmetry.

Codes JEL : C32, E31, E32, Q43