- Home

- Deputy governors' speeches

- Global imbalances: old wine in a new bot...

Global imbalances: old wine in a new bottle

Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Second Deputy Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 28th of January 2026

Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, January 2026

France has just taken over the presidency of the G7 for 2026 (from Canada in 2025).

One of the presidency's main priorities is to reduce "excessive” current account imbalances, or at least to identify policies that would enable these imbalances to be reduced in a concerted manner, while preserving growth in the countries concerned.

Meanwhile, as the United States takes over the presidency of the G20 from South Africa, which held it last year, reducing current account imbalances will also figure among its priorities.

So why all this fuss over global imbalances? Admittedly, the Trump administration is exerting strong pressure, with the excesses we are familiar with and a range of inappropriate remedies (tariffs). However, the growing global imbalances raise serious economic questions and they require a collective response.

The issue is not a new one

Current account imbalances are a natural consequence of international capital mobility. Without capital mobility, it is impossible for a country to spend more than its current income because it cannot borrow from other countries. Imbalances are a good thing if they enable better international allocation of capital. For example, an advanced, ageing country will invest its savings in younger developing countries with higher marginal productivity of capital. It’s a win-win situation for everyone: for savers, because the return on their savings increases, and borrowers, because foreign capital is cheaper than domestic savings (the latter being often limited and therefore more expensive).

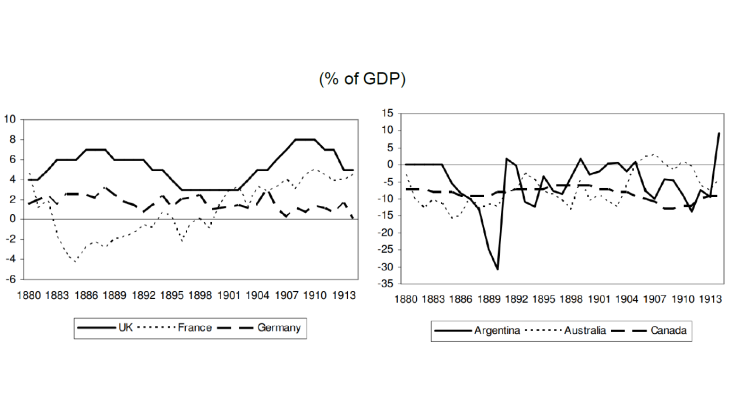

The first wave of financial globalisation (1870-1914) is a good illustration of this mechanism, with massive flows of capital from Western European countries to their colonies and former colonies, mainly to finance the construction of railways and other infrastructure. During this period, the British current account surplus fluctuated between 4% and 8% of GDP, while Canada, Australia and Argentina frequently recorded double-digit deficits as a percentage of their GDP (Chart 1). These imbalances persisted over several decades, but we can see that it was a turbulent period for Argentina, particularly in the wake of its first sovereign debt default in 1890.

Chart 1. Current account surpluses and deficits during the first wave of financial globalisation

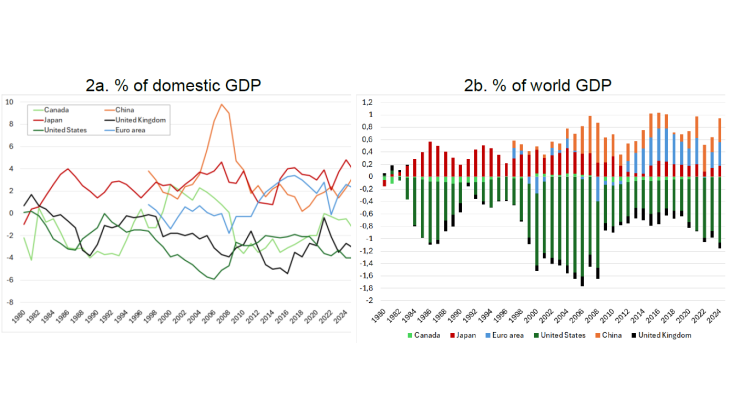

At first sight, current account imbalances in the 21st century do not appear any different from those of the 19th century: they are of the same order of magnitude and similarly persistent (Chart 2a). Nevertheless, the historian Michael Bordo (2006) highlights three differences: (i) the countries running a deficit are no longer necessarily emerging or low-income countries (and the dominant country, the United States, is in deficit, whereas the United Kingdom in the 19th century was in surplus), (ii) gross capital flows have increased exponentially relative to net flows (so there are many capital flows in both directions, with net capital flows equal to the current account balance), and (iii) floating exchange rates should theoretically allow imbalances to be corrected more rapidly, but this does not appear to be the case.

Twenty years after Michael Bordo, we may add that (iv) imbalances have persisted, despite the efforts of the G20 to reduce them, and (v) China's surplus, which is not exceptional as a percentage of domestic GDP (although this point is debated), is growing as a share of global GDP (Chart 2b), since its GDP has increased from 3% of global GDP in 1997 to 16.6% in 2025 (in current dollars).

Chart 2. Current account balances of G7 countries and China, 1980–2025

Why worry about imbalances?

One might argue that if countries with high savings rates are willing to finance countries with low levels of savings, it is because they see benefits in doing so. These savings finance productive investments that will ultimately generate income to reward and reimburse savers. So why worry about imbalances? Let us immediately disregard imbalances that are temporary, because they are linked to the business cycle, or those that are permanent but can be explained, for example, by demographics (see the International Monetary Fund's External Sector Report). It is excessive imbalances that are cause for concern, for at least three reasons.

First, these imbalances rarely get resolved painlessly. Two recent examples illustrate this point:

- Capital flows temporarily dried up in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, forcing current account adjustments to be made: Chart 2b shows a rapid reduction in the US current account deficit from 1.1% of global GDP in 2008 to 0.6% the following year. Although 2008 was not a balance of payments crisis, the role of deficits in the increase in risks over the decade preceding the crisis was rapidly recognised: capital inflows into the United States kept market interest rates low, encouraging households and financial intermediaries to take on more and more debt, something that was also encouraged by deregulation (see Caballero and Krishnamurthy, 2009, Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2009).

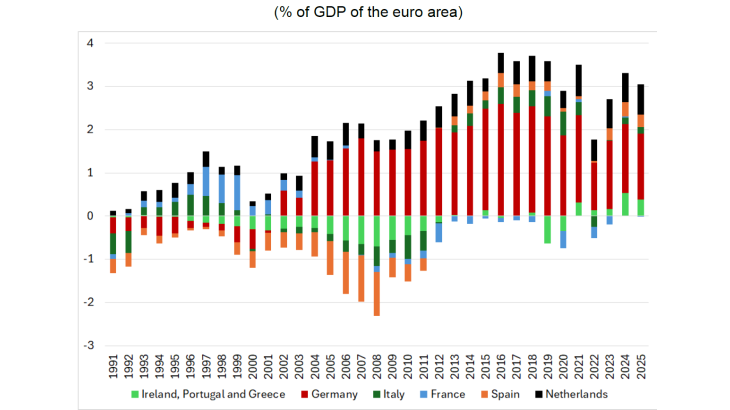

- The euro area sovereign debt crisis (2010-15) also led to sharp current account adjustments in several countries that were initially in deficit, without the countries in surplus reducing their excess of savings over investment (Chart 3). This resulted in insufficient aggregate demand in the euro area and sustained deflationary pressure.

The “sudden stop” in foreign financing is a traditional trigger for a crisis in countries running cumulative deficits. These crises can have negative repercussions in other countries through trade and, most importantly, financial interconnections. In countries running surpluses, the lack of any adjustment poses a deflationary risk. By providing financing to countries running deficits, sometimes without fully assessing the risks, countries with surpluses are also partly responsible for debt crises.

Chart 3: Current account balances of selected euro area countries, 1991–2025

Second, current account imbalances result from massive gross capital inflows and outflows that are rarely balanced in terms of currency, maturity, liquidity or credit risk. These differences in gross capital flows may pose risks to the global economy.

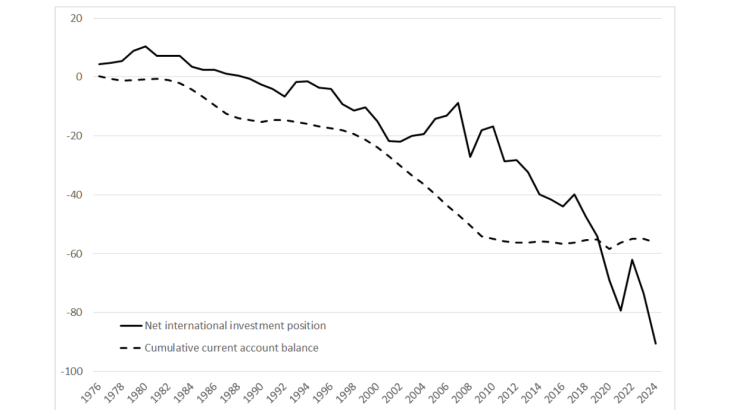

In the 2000s, the United States borrowed in the form of short-term dollar-denominated government bonds to invest in risky foreign assets denominated in foreign currencies. It therefore acted as a “global insurer”, pocketing the difference in the trend revaluation between their assets and liabilities (Gourinchas and Rey, 2014). In the 2000s, this configuration enabled the United States to avoid a trend deterioration in its net international investment position, despite accumulated deficits, while acting as a buffer during the 2008 crisis (Chart 4).

However, the situation reversed after the crisis, with the sharp increase in foreign investment into US corporate equities. The revaluation of the US stock market led to an increase in liabilities and therefore a deterioration in the US net international investment position, even though the cumulative current account deficit as a share of GDP remained stable (since nominal GDP growth was offsetting the additional flow of deficit). If the US equities market were to reverse, this time the impact of the loss would be felt throughout the rest of the world. It will be even greater if the dollar ceases to play its role as a safe haven and loses value, as was briefly the case in April 2025, following the Trump administration's announcement of “reciprocal” tariffs. Markets seem to be increasingly expressing doubts about the dollar's resilience in the face of the Trump administration's economic, institutional, and geopolitical choices.

Chart 4: Net international investment position and cumulative current account balance of the United States (as a % of GDP)

The problem is that these investments in the United States are often made through investment funds – sometimes with leverage. In the event of a downturn in the equity markets, these funds will lose value, scaring off subscribers and creditors. They will then have either to sell off their assets despite losses – exacerbating the fall in prices – or to draw upon bank credit lines, which could cause banks to restrict lending to non-financial companies and households.

The idea of twin crises (a combination of a balance of payments and a financial crisis) is not new (Kaminsky and Reinhart, 1999). It takes different forms over time, and the risk today could be from the rapid development of non-bank financial intermediaries, some of whom are both heavily indebted and exposed to liquidity risk (i.e. their assets are less liquid than their liabilities). The US external deficit is no longer financed primarily by the official sector (central banks and sovereign wealth funds), but by the private sector, which could prove to be more volatile.

The third reason to be concerned about large and persistent imbalances is that they may reveal economic distortions or even deliberate policies that block adjustments, generating negative externalities for partner countries. The most obvious case is intervention in the foreign exchange market, when a country blocks the appreciation of its currency by directly or indirectly increasing its foreign exchange reserves, while sterilising these interventions to also block the resulting inflation. Production subsidies in China, estimated at around 4% of GDP per annum by Garcia-Macia et al. (2025), combined with a proactive import substitution policy, are often cited as preventing a reduction in China's current account surplus. This is compounded by a persistent excess of savings in China, linked to the still insufficient coverage of the population in terms of health insurance and pensions (Lardy, 2025). Chinese businesses are encouraged to overproduce compared to domestic demand, which is failing to take off.

Companies in China's partner countries are protesting against violations of global economic rules and demand – sometimes successfully – trade protections that are suboptimal from a collective perspective. In some countries, excessive or persistent deficits (and therefore foreign capital inflows) can also contribute to misallocation of capital, particularly through excessive development of the finance, construction and real estate sectors (see Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2005 and Benigno et al., 2025 for the United States, and Giavazzi and Spaventa, 2010, and Gopinath et al., 2017, for the euro area).

A global planner would know what to do

Statistical errors aside, there cannot be a deficit in one country without a surplus in another. So countries with deficits and those with surpluses do not need to agree: one side simply needs to reduce its imbalance for the imbalance on the other side to automatically decrease.

Nevertheless, a unilateral strategy would be very risky for the global economy. Imagine, for example, that the US administration decides to rapidly reduce its budget deficit. As US households have little room for manoeuvre in reducing their savings (which are already low), this would result in a slowdown in global demand for goods and services, and thus a weakening of growth, not only in the United States but also in countries running a surplus where growth is partly export-driven. Admittedly, an improvement in the US fiscal trajectory could ease market interest rates. However, it is by no means certain that this would be sufficient to sustain global growth during the adjustment period.

Conversely, suppose that China and the euro area both find a way to rapidly reduce their savings rates or, in the case of the euro area, boost their investment rates. The impact would be favourable for global growth. However, the amount of net savings available to countries in deficit – particularly the United States – would be reduced, pushing up market interest rates. Moreover, demand would increase not just for tradable goods (which by definition can be imported), but also for non-tradables, pushing up the prices of the latter. Central banks would react by monetary tightening. Given the accumulated risks in the financial sector, a sharp rise in interest rates could lead to financial instability.

This is why a coordinated strategy is needed, based on consistent economic policy commitments. A simultaneous and gradual reduction in the US budget deficit and in the savings surpluses in China and the euro area could both preserve (or even strengthen) global growth and keep real interest rates at a relatively low level, as demonstrated by the International Monetary Fund in its World Economic Outlook of April 2025 (Box 1.2).

The French presidency of the G7 will strive to reconcile differing views on whether observed imbalances are excessive, on the policies likely to reduce them, and finally on the measures to be taken to limit the risk of an abrupt and disorderly rebalancing. The progress made by the G7 will be useful in initiating dialogue with China and, more generally, with the major emerging economies, particularly during the US presidency of the G20. This work will draw upon quantitative analyses by the International Monetary Fund and the OECD.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 28th of January 2026