Post No. 427. Since 2021, the gap between the Chinese trade surplus as measured by customs and the figure published in the balance of payments has widened markedly, raising questions over the reliability of the data. The divergence can be attributed to a change in the data sources used in the balance of payments, to take better account of international production arrangements. However, the change does not appear to have been applied to the years prior to 2021.

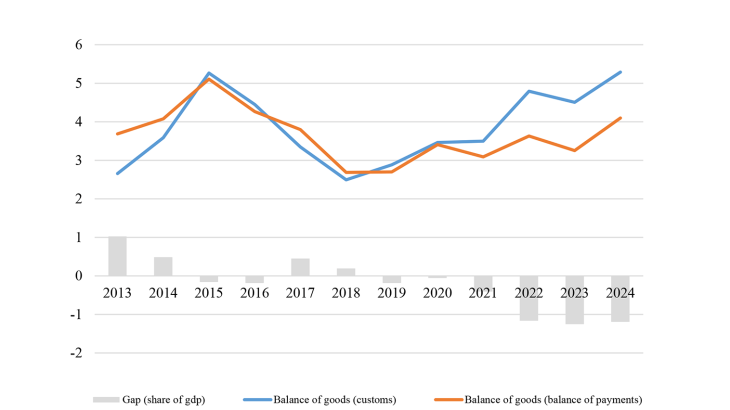

Chart 1: China, balance of trade in goods (percentage points of GDP)

In China's balance of payments, the balance of trade in goods has increased moderately in recent years, from 2.8% of GDP in 2019 to 3.3% in 2023. At the same time, the balance as measured by Chinese customs has increased much more sharply, from 2.9% to 4.6% (Chart 1). More specifically, in 2022 and 2023, China's trade surplus was significantly higher according to customs data than according to the balance of payments. Against a backdrop of heightened trade tensions, the widening gap between customs data and balance of payments data for China has attracted staunch criticism, particularly from the economist Brad Setser (China’s Imaginary Trade Data). It notably raises questions over how to accurately measure global imbalances. How does the gap compare with that in other countries and how should it be interpreted?

The gap between customs and balance of payments data reflects methodological differences

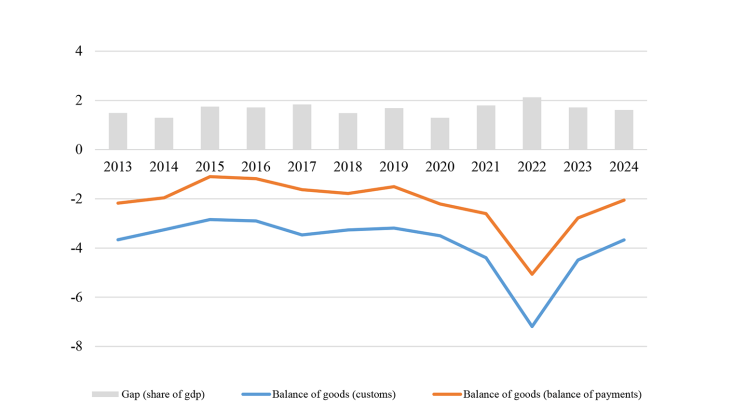

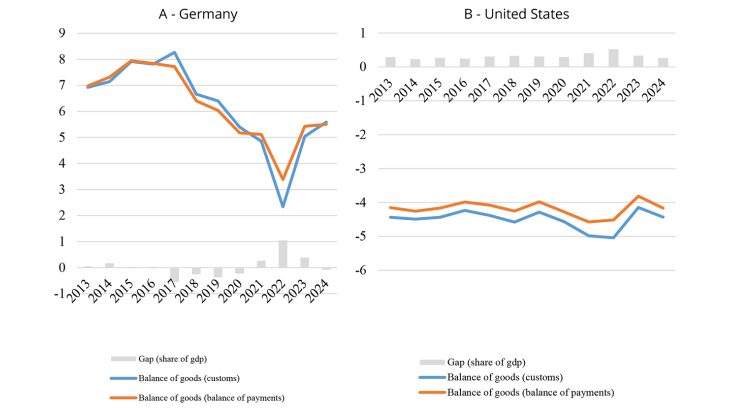

In France’s case, a large gap can be observed in the data – albeit in the opposite direction to China’s – but it has remained relatively stable over time (Chart 2). Gaps can also be observed for numerous other countries, such as Germany and the United States (Charts 3A and B).

The divergences are frequent and can be attributed to methodological differences. Customs authorities notably record goods when they cross their national border, whereas in the balance of payments they are recorded when there is a transfer of ownership between a resident and non-resident, in accordance with the 6th Balance of Payments Manual (BPM6).

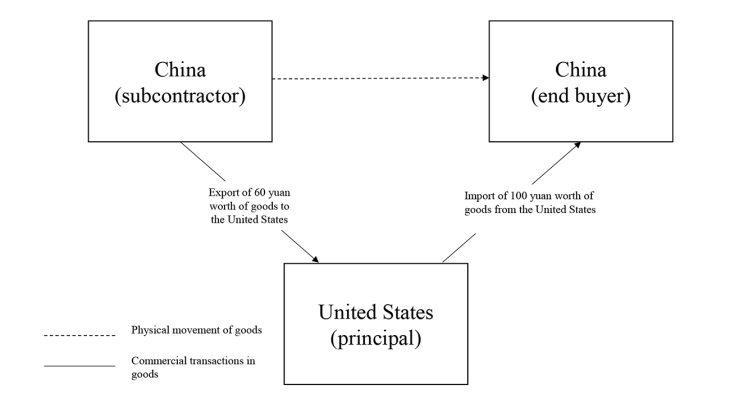

For example, if an American company (Principal) has a good manufactured in China by a Chinese company (Contractor), buys it for 60 yuan and resells it to a Chinese consumer for 100 yuan, then (see Diagram 1):

- China’s balance of payments will record an export to the United States of 60 yuan and an import of 100 yuan;

- Chinese customs will record neither an import nor an export, since the goods did not cross the border.

In total, in this simple illustration, the balance of goods will be -40 yuan in the balance of payments and 0 according to customs data. Conversely, the balance will be +40 yuan in the US balance of payments and 0 in US customs data.

Diagram 1: Example of trade exchanges under international production arrangements

For France and many other countries, including the United States and Germany, customs data are the main source used to measure trade in goods in the balance of payments, but several adjustments are then made to comply with BPM6 guidelines.

Trade in goods that change ownership without crossing a border is added to the balance of payments. This includes:

- goods procured in ports by carriers (purchases for ships and aircraft, e.g. fuel and provisions);

- purchases and resale of products after they have been processed under international production arrangements, without the product crossing a national border;

- merchanting, which consists in purchasing goods for resale without processing and without the goods entering the economy under review.

The adjustments also include an estimate of trade in goods that cannot be recorded by customs. These are essentially illegal economic activities such as trade in contraband tobacco and narcotics.

Conversely, trade without any consideration or transfer of ownership, such as gifts or certain movements of goods for repair or processing as part of intra-group manufacturing, is excluded from the balance of payments.

Moreover, customs data are generally published on a “CIF-FOB” basis, in other words imports include the cost of insurance and freight (CIF), whereas exports are measured at their value at the border (FOB, for “free on board”). In the balance of payments, trade in goods must be recorded as “FOB-FOB”. To do this, insurance costs and transport costs as far as the border are subtracted from the value of imports of goods (CIF-FOB adjustment) and reclassified as imports of services. The goods balance is larger on an FOB-FOB basis than on a CIF-FOB basis, but the adjustment has a neutral impact on the goods and services balance.

Gaps between customs and balance of payments data are generally stable over time

In France’s case, the gap has averaged 1.7 percentage points of GDP over the past decade (Chart 2). It is mainly attributable to the CIF-FOB adjustment (0.8 percentage points of GDP in 2024), merchanting (0.6 percentage points of GDP in 2024) and the incorporation of general merchandise not covered by customs, including goods procured in ports by carriers (0.4 percentage points of GDP in 2024). Regarding general merchandise not covered by customs, from the example given in Diagram 1, it is hardly surprising that they contribute positively to the gap between the balance of payments and customs trade balance, since French firms are more likely to be originators than subcontractors, unlike Chinese firms.

Chart 2: France, balance of trade in goods (percentage points of GDP)

In Germany’s case, the divergence between customs and balance of payments data is smaller than in France, but is less stable and changes direction over time. This is mainly due to cyclical factors linked in particular to trade in goods such as electricity and gas, which require specific adjustments in the balance of payments. The most notable example is German energy merchanting firms which buy and sell gas and electricity without any physical flows passing through Germany. The rise in energy prices as of 2021 contributed both to the increase in the gap and the deterioration in both balances.

For the United States, over the past decade, the main source of the gap between the customs and balance of payments balance is the CIF-FOB adjustment, which explains why it has remained relatively stable over time.

Chart 3: Germany and the United States, balance of trade in goods (percentage points of GDP)

In China’s case, the widening of the gap is thought to stem from a change in data source

According to an IMF report (Article IV, 2024), until 2021, Chinese balance of payments authorities used customs data as the main source for constructing trade in goods series. They now use data reported by firms and banks. This change in source is designed to make it possible to factor in changes in ownership directly. However, this methodological change is unlikely to have led to a backcasting of data, as exports and imports have been revised only slightly in previous years.

Differences between physical trade in goods (customs data) and economic transactions (balance of payments) can be particularly significant when the country in question is heavily involved in global production arrangements, as is the case with China. In its report, the IMF specifically refers to the concept of “factoryless manufacturing”, where a non-resident firm designs goods and controls their production then subcontracts their manufacture to a resident entity. In this case, illustrated in Diagram 1, the import recorded by China in its balance of payments but not by customs reflects the value added provided by the foreign firm which has had the good made in China, notably research and development and marketing.

Overall, without wishing to pass judgement on the quality of the data, the method used in China’s balance of payments since 2021 appears to be consistent with the conceptual framework established in BPM6. However, the absence of a gap between the two balance of goods measures prior to 2021 raises an issue and suggests there has been no backcasting of data using the new method.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 16th of January 2026