- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- Macroeconomic projections – December 202...

In order to contribute to the national and European economic debate, the Banque de France periodically publishes macroeconomic forecasts for France, constructed as part of the Eurosystem projection exercise and covering the current and two forthcoming years. Some of the publications also include an in-depth analysis of the results, along with focus articles on topics of interest.

Projections macroéconomiques – Décembre 2025

- Our new macroeconomic projections were finalised in early December amidst major domestic uncertainty. As budget discussions are still ongoing, as was the case last year, the projections are based on a conventional assumption for 2026 underpinned by the government’s Draft Budget Act and the Social Security Financing Bill. However, less fiscal consolidation than that envisaged in the draft legislation would not lead to surplus growth, as prolonged fiscal uncertainty would still result in more cautious behaviour from households and businesses.

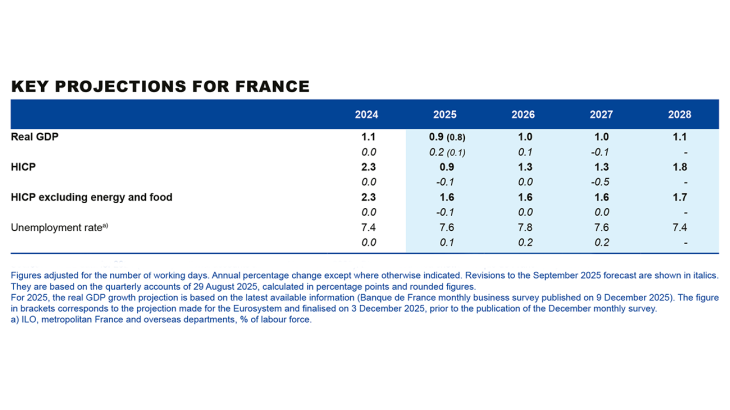

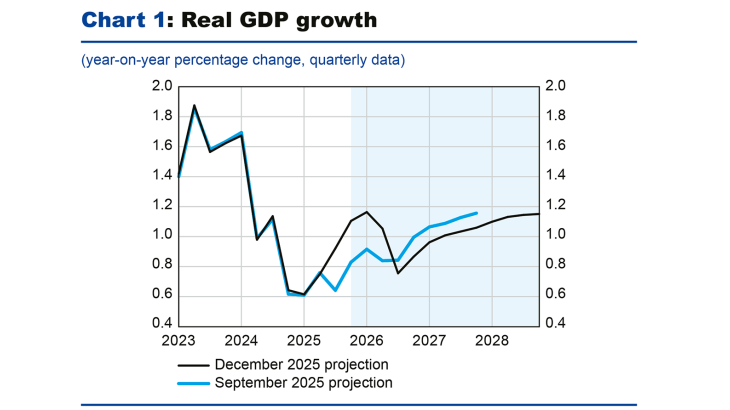

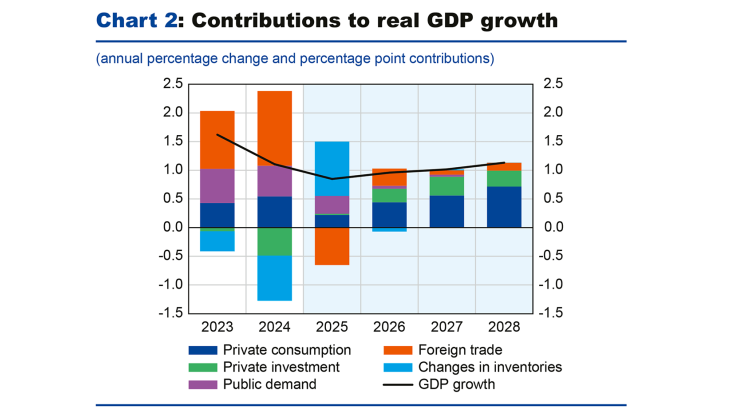

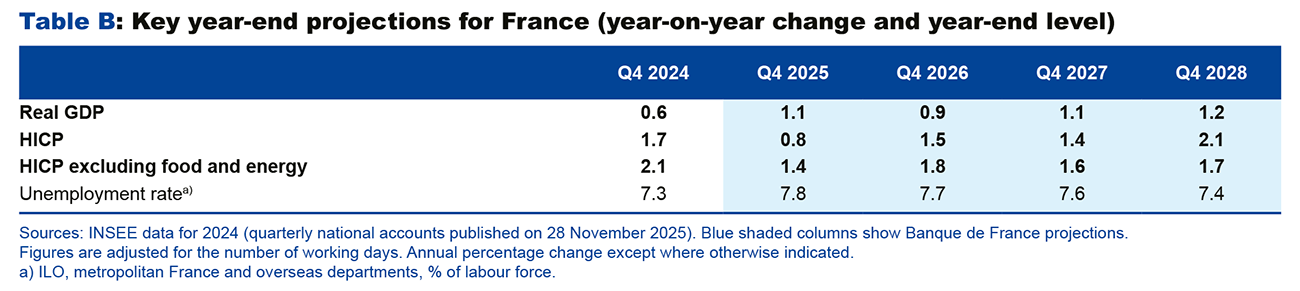

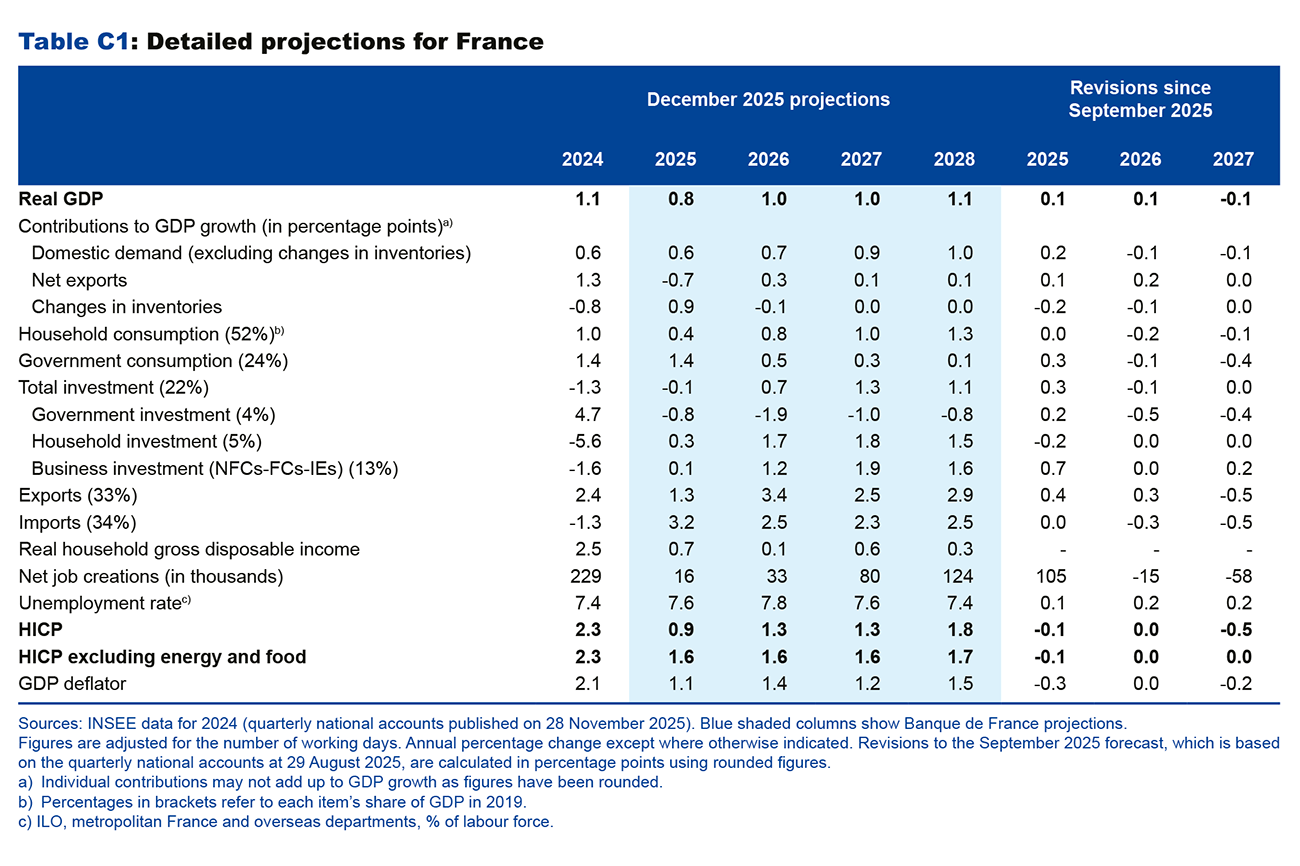

- In light of its 0.5% increase in the third quarter of 2025, and the latest information available for the fourth quarter, GDP is expected to grow by an annual average of 0.9% in 2025, after the 1.1% increase recorded in 2024. Activity has been driven mainly by the production of transport equipment (aeronautics), with restocking in the first half of the year in anticipation of very strong exports in the second half. Growth is expected to strengthen slightly to 1.0% in 2026 and 2027, and to 1.1% in 2028, buoyed by a recovery in household consumption and private investment.

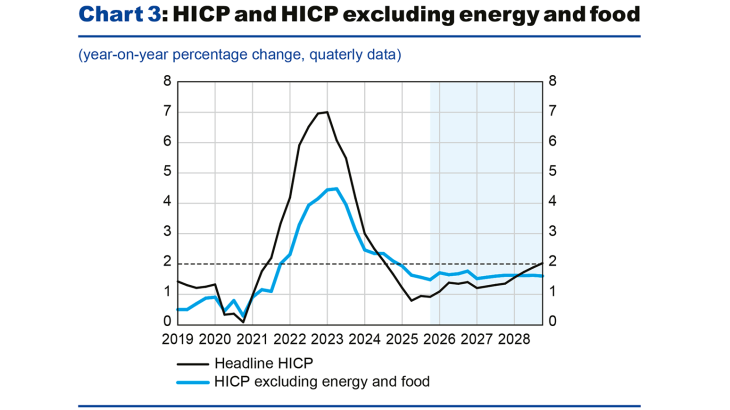

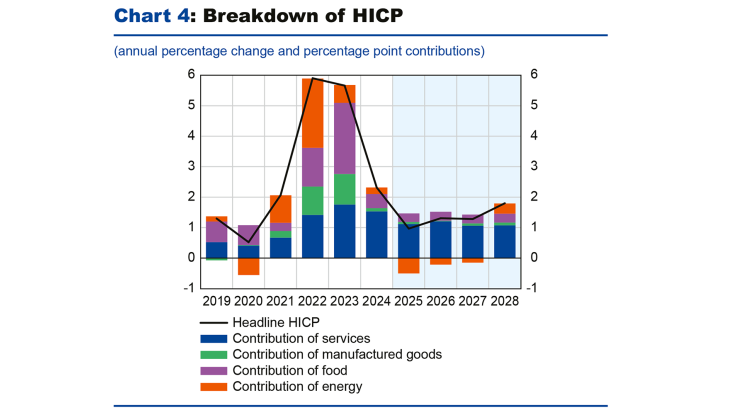

- Inflation should remain below 2% over the projection horizon. After the figure of 2.3% recorded for 2024, average annual headline inflation (HICP) is expected to bottom out in 2025 at 0.9%, driven down by the sharp decline in energy prices in the wake of the fall in regulated electricity and oil prices. It should then rise to 1.3% in 2027, and to 1.8% in 2028. Inflation excluding energy and food – mainly caused by services inflation – is expected to remain broadly stable over the projection horizon (i.e. at around 1.6% to 1.7%).

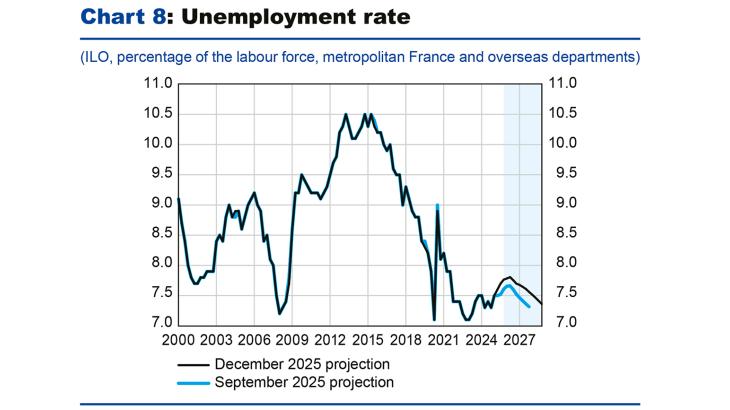

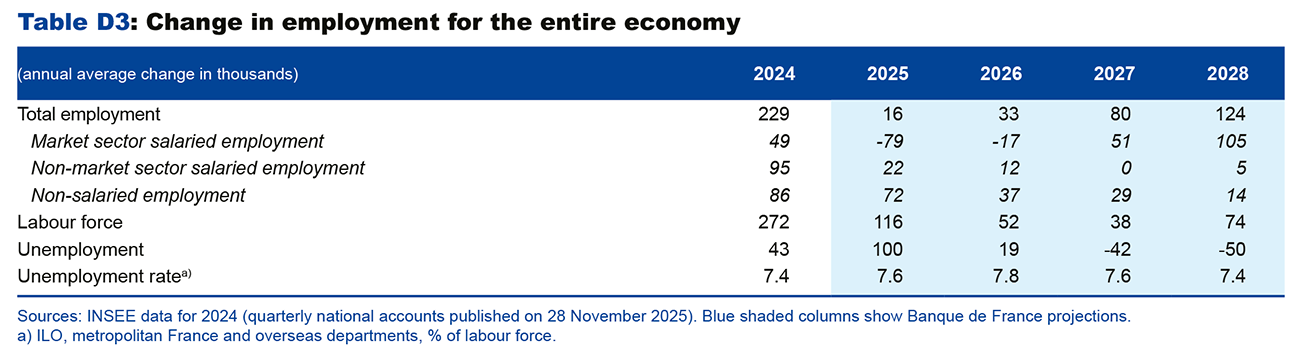

- After relatively sluggish growth in 2025, due in particular to high levels of savings linked to current uncertainty, household consumption should grow in a fairly sustained manner in 2026, underpinned by purchasing power gains from increases in the average wage per employee and then by job recovery from 2027 onwards, assuming lower levels of political and fiscal uncertainty. The unemployment rate of 7.7% in the third quarter of 2025, is expected to rise slightly in 2026, before declining to 7.6% in 2027 and to 7.4% in 2028.

- The risks surrounding the growth outlook are balanced on the whole. Recent upside surprises in economic activity could represent the first signs of a faster rebound in private demand. Conversely, continued political and fiscal instability are expected to continue to weigh on both household consumption and business investment. The uncertainties surrounding inflation stem in particular from import prices (raw materials, exchange rates, increase in Chinese imports, etc.) in an uncertain international context.

Upside surprises in economic activity have resulted in a slight upward revision of growth forecasts for 2025 and 2026

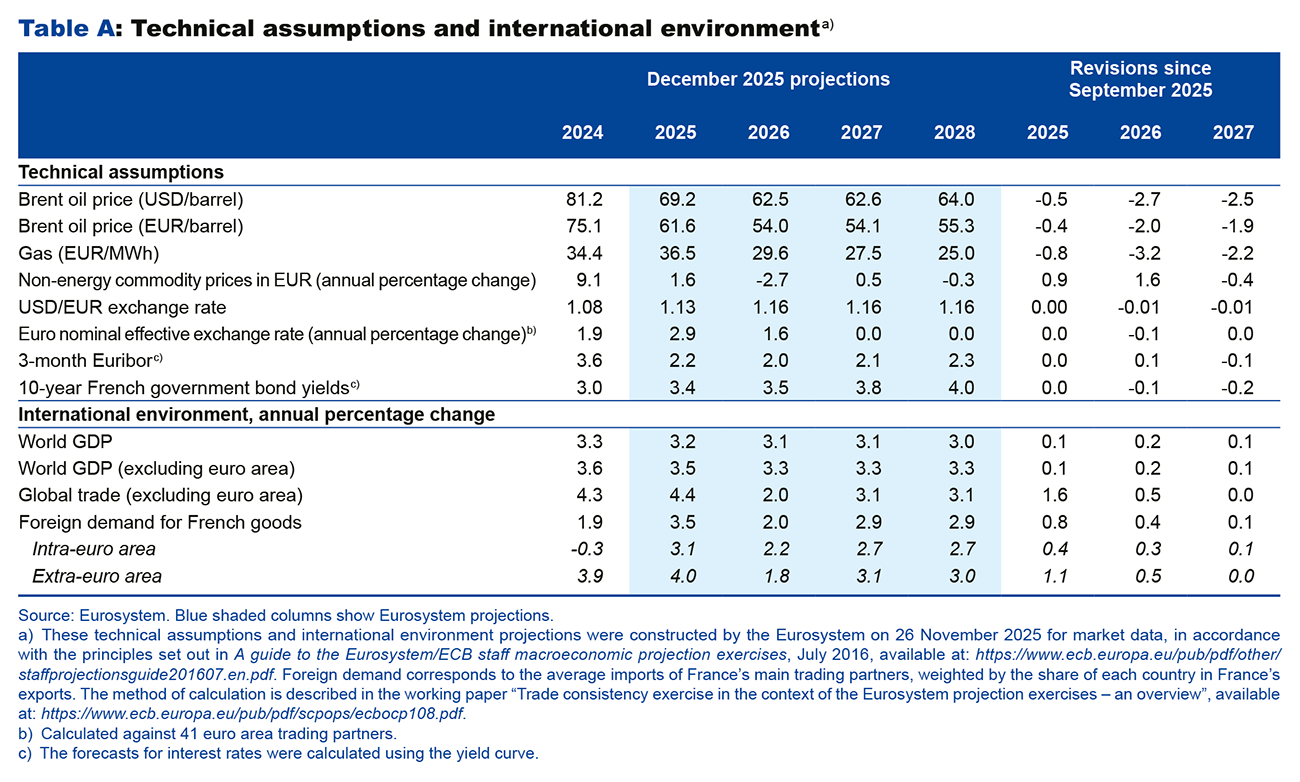

This projection, which was finalised on 3 December 2025, incorporates the detailed results of the third quarter 2025 national accounts published on 28 November 2025, and the flash estimate of HICP (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices) inflation for November, also published on 28 November. It is based on Eurosystem technical assumptions, for which the cut-off date is 26 November 2025 (see Table A). Finally, in the absence of the approval of the budget law, it incorporates public finance assumptions based on the Draft Budget Act and the Social Security Financing Bill for 2026, presented on 14 October (see the section on public finances). The projection does not reflect any legislative changes that have taken place since then.

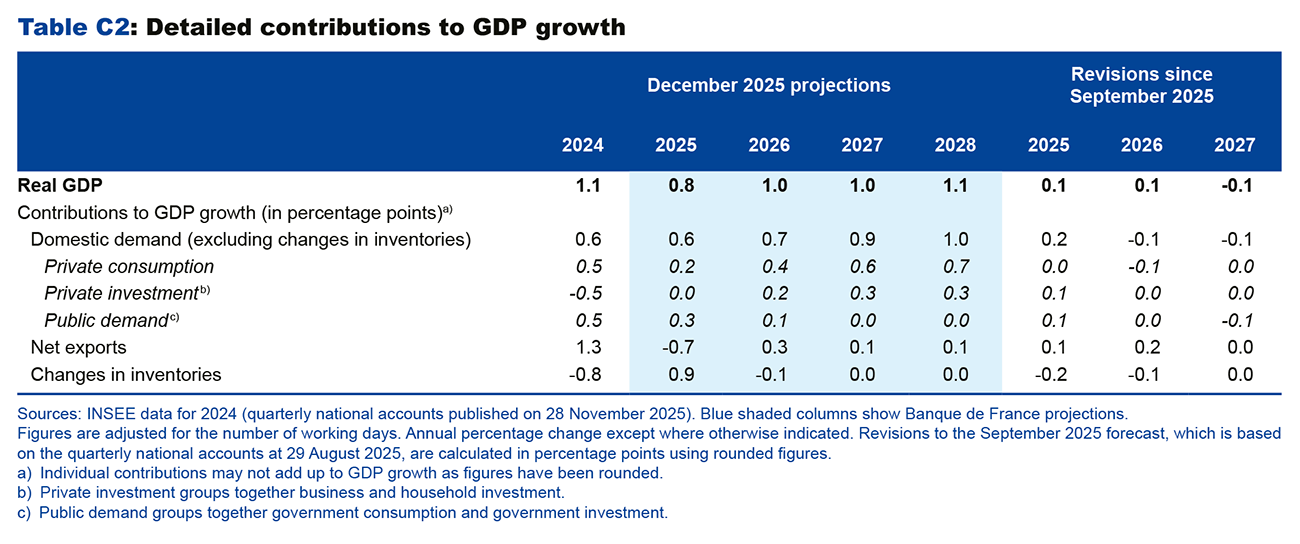

GDP growth in the third quarter of 2025 was 0.5%, well above our September forecast. This peak in activity explains the uneven trajectory of our year-on-year GDP forecast (see Chart 1). Activity was buoyed by exports (particularly transport equipment), government consumption and business investment, while household consumption continued to grow at a very moderate pace. This upside surprise reflects a higher carry-over effect from the third quarter, both for 2025 and 2026.

According to the results of the Banque de France’s latest Monthly Business Survey published on 9 December (but only available after our projections had been finalised), GDP is expected to grow by 0.2% in the fourth quarter. These short-term upside surprises suggest average annual real GDP growth in 2025 of 0.9% (compared with 0.8% in the projection finalised on 3 December), revised upwards from our September interim forecast of 0.7%.

For 2025 as a whole, the main positive contribution to average annual growth should come from changes in inventories, which should offset the negative contribution from the net external trade balance. However, these two opposing trends need to be analysed jointly, insofar as they both result largely from the quarterly report on transport equipment, with imports and storage of aircraft parts in the first half of the year, followed by exports and destocking of aircraft in the second half (see Box 1). Government consumption is expected to remain buoyant in 2025 and to continue to outpace GDP growth, while household consumption (0.4%) is again expected to grow at a slower rate than the purchasing power of disposable household income (0.7%), leading to a further increase in the average annual saving ratio (to 18.5%, following a rise of 18.2% in 2024).

In 2026, annual GDP growth should come in at 1.0%, up 0.1 percentage point compared with our September projections, mainly due to the upward revision in growth carry-over at the end of the third quarter of 2025. The contribution of foreign trade is expected to be positive to the tune of 0.3 percentage point, up 0.2 point compared to our September projections, thanks in particular to sustained export activity in the second half of 2025. Therefore, the uncertainty over US trade policy in 2025 should weigh less on growth in 2026, provided that the recently concluded bilateral trade agreements are not called into question. Household consumption (up 0.8%) is expected to grow at a faster rate than in 2025, buoyed by growth in real wages, which should remain resilient despite a less favourable labour market. After suffering from uncertainty in 2025, annual average business investment should also recover (see Box 2) and household investment is expected to gradually pick up in 2026 after slightly positive growth in 2025.

In 2027, annual average activity is expected to grow at the same rate as in 2026 (i.e. 1.0%), but the quarterly growth rate should be slightly higher. Business investment is expected to be buoyed by final demand, provided there is no resurgence of political and fiscal uncertainty. Household consumption is forecast to be slightly more dynamic than real income, leading to a slight decline in the saving ratio.

In 2028, annual growth of 1.1% is expected to be close to its rate of potential growth, buoyed mostly by domestic demand and by the contribution of foreign trade to a lesser extent.

The French economy is expected to continue to be affected by international or domestic exogenous shocks. In particular, the direct negative impact of US tariffs on French activity is forecast to be 0.1 percentage point of GDP – the same as in our September forecast – concentrated mainly in 2026. Economic policy uncertainty, as measured by the Trade Policy Uncertainty (TPU) index is expected to be a negative cumulative 0.2 percentage point of GDP for 2025 and 2026, revised downwards from our previous estimates in line with better-than-expected trends in this indicator. We estimate that uncertainty over domestic economic policy will cost the French economy just over 0.2 percentage point of GDP, with the impact concentrated in 2025 and in 2026 to a much lesser extent. It is expected to weigh essentially on household consumption and business investment (see Box 2 on the impact of tax and fiscal uncertainty on investment).

Compared with our previous September projections, GDP has been revised upwards by a cumulative total of 0.2 percentage point for 2025-27, with positive revisions of 0.2 percentage point of GDP in 2025 and 0.1 percentage point in 2026, and a negative revision of 0.1 percentage point in 2027. The positive revisions in 2025 and 2026 are mainly due to upside surprises in economic activity in the second half of the year, which have pushed up annual growth in GDP in 2025, and the impact of the carry-over effect on annual growth in 2026. Growth is also benefiting from more favourable assumptions regarding total foreign demand for French goods and services, long-term interest rates and energy prices (downward revision of wholesale prices for oil, gas and electricity). Conversely, fiscal assumptions are forecast to have a negative impact on growth in 2027, due in particular to a higher structural adjustment assumption that would reduce consumption and public investment.

A gradual rise in inflation, which should nevertheless remain below the 2% threshold

In November 2025, HICP (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices) inflation was 0.8% year-on-year, based on INSEE’s final estimates, after measuring 0.8% in October 2025. Inflation excluding energy and food stood at 1.2% year-on-year in November 2025, after measuring 1.5% in October 2025. Average annual headline inflation for 2025 is expected to remain at only 0.9%. This weak inflation is mainly attributable to the reduction in regulated electricity tariffs at the beginning of the year. Inflation excluding energy and food (at 1.6%) should mainly be impacted by the contribution of services.

In 2026, headline inflation and inflation excluding energy and food are expected to measure 1.3% and 1.6% respectively. Headline inflation should be higher due to the stabilisation of energy prices (following the sharp fall in electricity prices one year earlier). This forecast factors in the fiscal and social measures provided for in the first draft of the government’s 2025 Budget Act and Social Security Financing Bill (doubling of medical deductibles and flat-rate contributions, and introduction of a tax on parcels from outside the EU with a value of less than 150 euros). However, since our projections were finalised, the Government has ultimately committed not to enact the decree to double medical deductibles and flat-rate contributions. This would imply a mechanical downward revision of headline inflation and inflation excluding energy and food projections for 2026, to 1.2% and 1.4%, respectively. Our forecast also factors in the expected scaling-up in early 2026 of the energy saving certificate programme, which is a component of the price of fuel, gas and electricity.

In 2027, headline inflation and inflation excluding energy and food are expected to remain unchanged at 1.3% and 1.6%, respectively. Inflation excluding energy and food should reflect private services prices (excluding health services, communication and rents), pushed up by growth in nominal wages. These projections also take account of the postponement until early 2028 of the introduction of the second European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS-2), whose impact was factored into our September interim projections in the figures for 2027, leading to a downward revision of headline inflation for that year.

Finally, headline inflation in 2028 is forecast to increase to 1.8% due to the impact of energy prices. These are expected to rise throughout the year, in line with the entry into force of the second European Union Emissions Trading System, although the impact of the new emission allowances remains highly uncertain given the compensatory measures that may be implemented. Inflation excluding energy and food should remain more or less stable at 1.7% and service prices should return to their long-term average, in line with the trajectory of wage growth.

In November 2025, the inflation differential between the euro area and France stood at +1.4 percentage points, significantly higher than the long-term average rate (+0.2 percentage point between 1999 and 2019). It widened particularly in February 2025 with the sharp drop in French regulated electricity prices. However, in recent months, the main contribution to this inflation differential has come from services, due to more moderate wage growth in France – which is itself partly the result of lower past inflation – and to a relatively higher unemployment rate in France. Looking ahead, headline inflation in France is expected to remain below euro area inflation, with services again making a significant contribution.

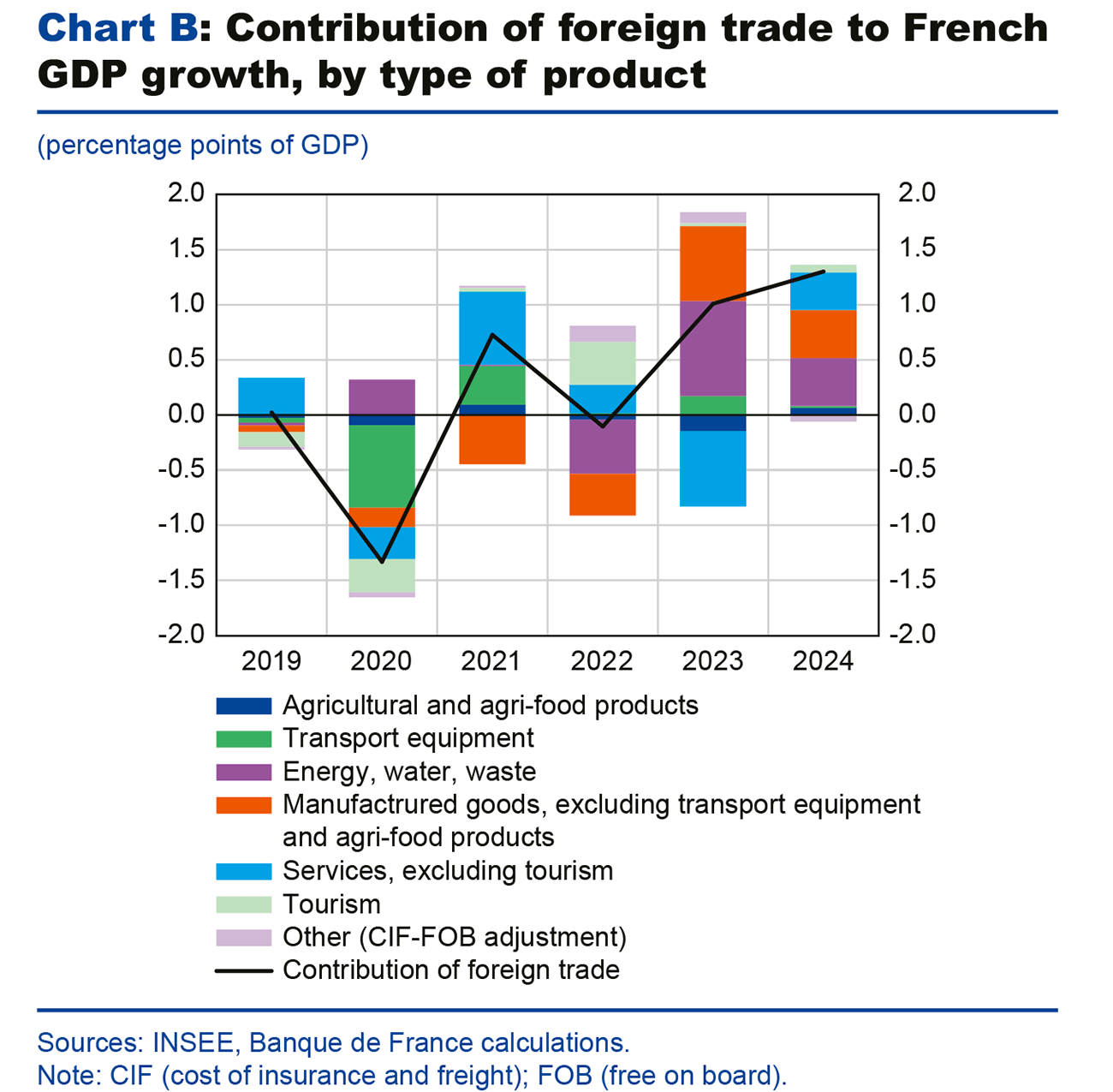

Note: CIF (cost of insurance and freight), FOB (free on board)

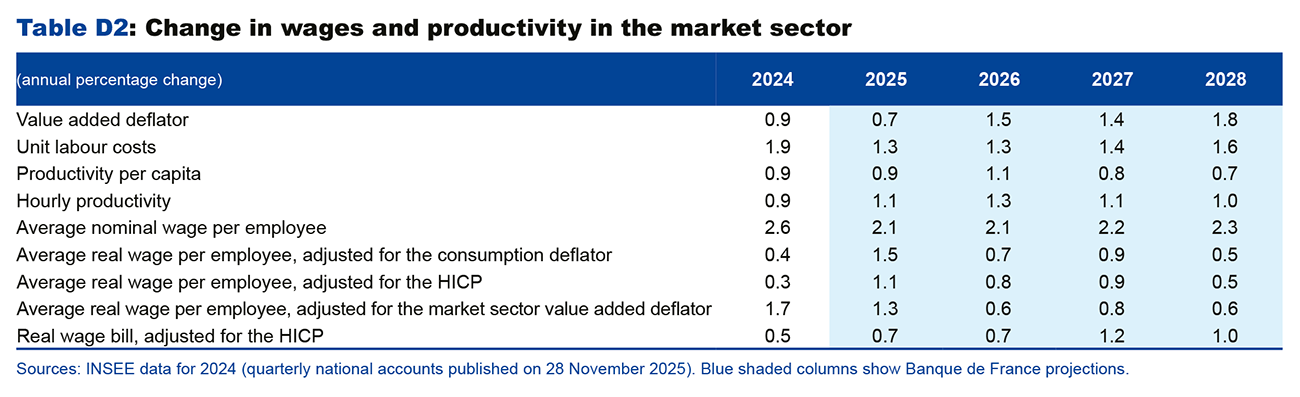

The purchasing power of the average wage per employee is expected to rise over the projection horizon

Our projection factors in the latest data concerning the monthly base wage (MBW), which rose by 2.0% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2025. It is also underpinned by the latest available observation of negotiated wages, which grew by 1.6% in the third quarter of 2025, according to the latest industry-level agreements and compulsory annual wage negotiations (NAOs).

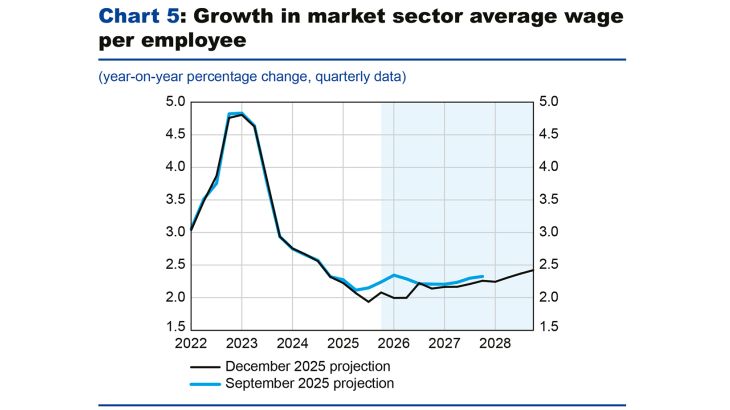

Since our September projections, the wage growth trajectory has been revised slightly downwards across the entire projection horizon for several reasons. In the short term, negotiated wage metrics indicate a faster-than-expected slowdown, leading us to adjust the average wage per employee trajectory in 2025 and 2026. In 2027, the downward revision of inflation compared to our September projections, due in particular to energy prices, results in a less buoyant trajectory for nominal wage growth per employee (see Chart 5). Overall, nominal wages are expected to increase by slightly more than 2% between 2025 and 2027, accelerating to 2.3% in 2028, in line with inflation, trend productivity gains and the gap between the unemployment rate and its structural level.

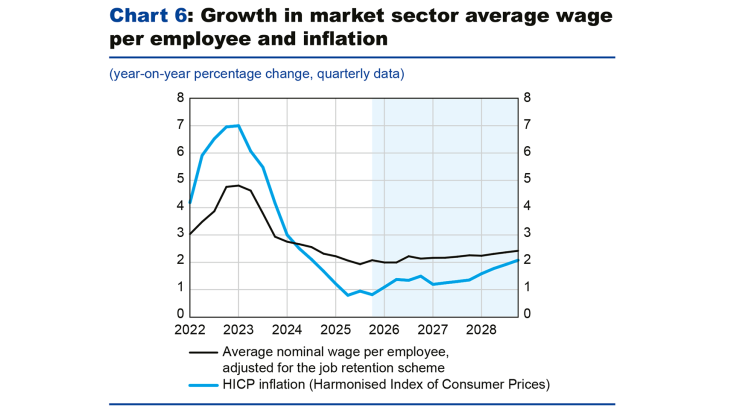

Although the average nominal wage per employee has been slowing in market sectors since the second half of 2023, it has been increasing faster than consumer prices since the second quarter of 2024, a trend that is projected to continue (see Chart 6).

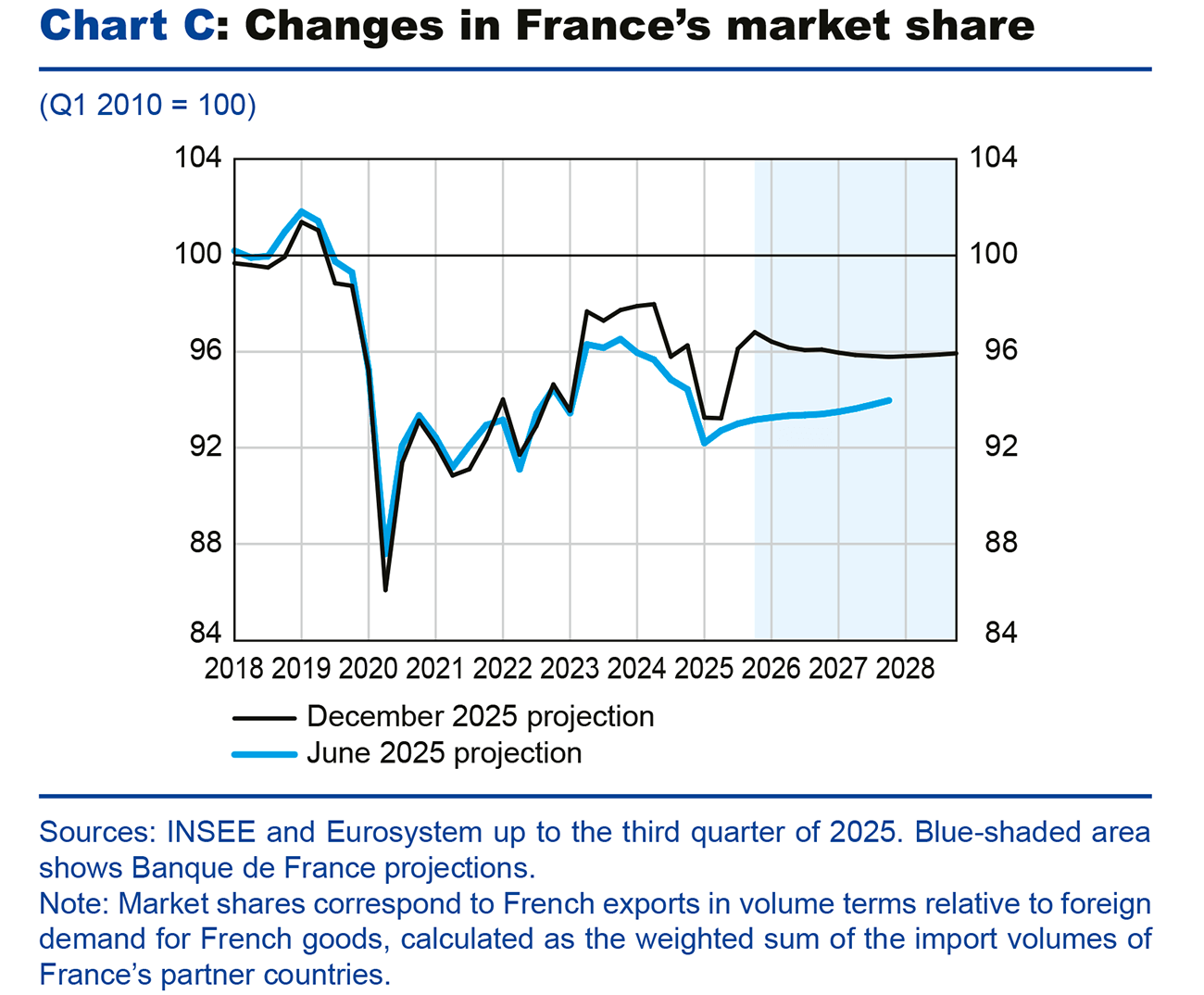

Note: Markes shares correspond to French exports in volume terms relative to foreign demand for French goods, calculated as the weighted sum of the import volumes of France's partner countries.

The unemployment rate is expected to rise slightly to 7.8% in 2026 before falling back to 7.6% in 2027 and then to 7.4% in 2028.

The latest economic indicators show that the labour market is “bending but not breaking”. On the one hand, the quarterly accounts published on 28 November show a slight increase in total employment in the third quarter of 2025 (+38,000 jobs), driven by public sector and non-salaried employment, while salaried employment in the market sector is virtually stable. On the other hand, according to INSEE’s economic survey for November, the employment climate remains below its long-term average despite a slight upturn.

According to our projections, total employment will continue to grow very moderately until the end of 2026, before picking up again, albeit at a slower pace than during the post-Covid recovery. The trajectory of salaried employment has been revised upward for the short term due to surprises on the upside in the first half of the year, but its recovery is expected to be slower and delayed when compared to our previous projections (see Chart 7), due to the reduction in public support for apprenticeships. Public employment also surprises on the upside for the short term but is supposed to be held back by fiscal adjustments starting next year.

Our assessment of long-term productivity losses compared to pre-Covid trends remains unchanged, with composition effects that offset each other. On the one hand, the rise in the share of non-salaried workers in total employment could increase the share of long-term productivity losses, as these jobs are on average less productive. On the other, reduced public support for apprenticeships – the growth of which has weighed on labour productivity in recent years – would have the opposite effect. Overall, the productivity cycle should continue to recover over our projection horizon and should have almost closed by the end of 2028.

According to the INSEE employment survey published on 13 November, the unemployment rate is expected to reach 7.7% in the third quarter of 2025, up 0.1 percentage point from the second quarter, which is slightly higher than forecasted in our September projections. As a result, our forecast is revised upwards compared with our September projections, by 0.1 percentage point in 2026 and by 0.2 percentage point in 2027. The unemployment rate is therefore expected to average 7.6% in 2025, then rise slightly to 7.8% in 2026, before falling again to 7.4% in 2028 (see Chart 8). These projections take into account the suspension of the pension reform until 2028 (included in the amendment to the Social Security Financing Bill presented to the Council of Ministers on 23 October 2025), which slows the growth of the labour force over our projection horizon.

Note: HICP, Harmonised Index Consumer Prices.

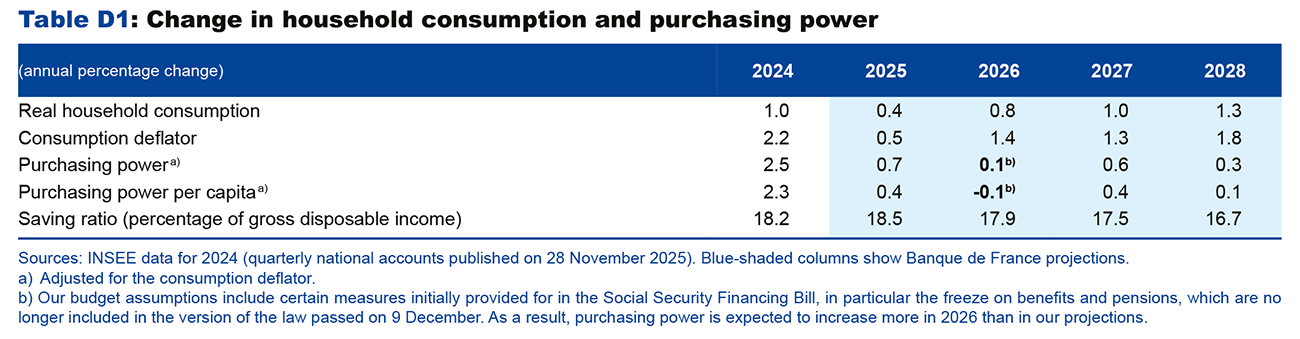

Household consumption is expected to support the recovery over the projection horizon

In 2025, household purchasing power is expected to continue to grow, albeit more moderately (0.7%), despite lower inflation, following the sharp rise recorded in 2024 (2.5%), on account of social benefits (pensions) and property income (interest rates). It should slow further in 2026, due to rising inflation, before picking up in 2027 and 2028. However, our budget assumptions included certain measures initially provided for in the Social Security Financing Bill, in particular the freeze on benefits and pensions, which are no longer included in the version of the law passed on 9 December. As a result, purchasing power in 2026 is expected to increase by more than in our projections. That said, if fiscal uncertainty were to persist, this would not lead to increased consumption but rather to a smaller decline in the saving ratio.

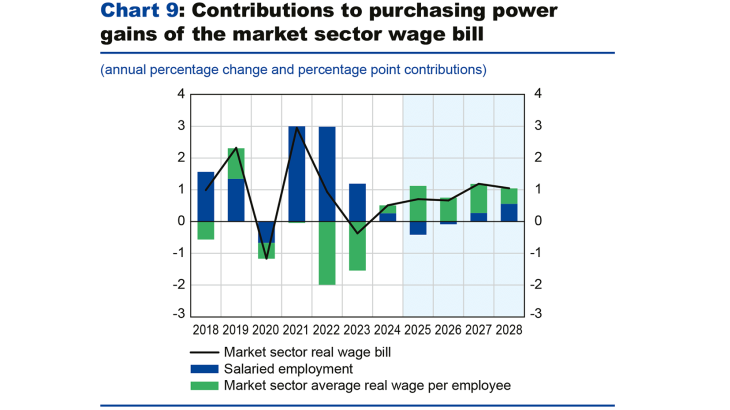

The purchasing power of market sector wages should grow steadily over the projection horizon (see Chart 9). In 2025, it should grow by 0.7%, driven by the rise in the real wage per employee, which would offset the decline in employment. The rise in average real wages per employee should remain significant in 2026 and 2027, and the recovery in employment should begin to be felt from 2027 onwards. The purchasing power of market sector wages is thus expected to rise by 0.7% in 2026, 1.2% in 2027, and 1.0% in 2028.

In the national accounts published on 28 November, household consumption in the third quarter of 2025 grew by 0.1%, a figure which is slightly below our September projections. After posting an average annual increase of 1.0% in 2024, it is expected to slow to 0.4% in 2025. It should then regain some momentum in the medium term, growing by 0.8% in 2026, 1.0% in 2027, and 1.3% in 2028. This improvement would be underpinned by purchasing power gains from the wage bill, assuming that household confidence recovers. However, when compared to our September projections, household consumption has been revised slightly downward in 2026, owing to a lower-than-expected purchasing power of wages in September.

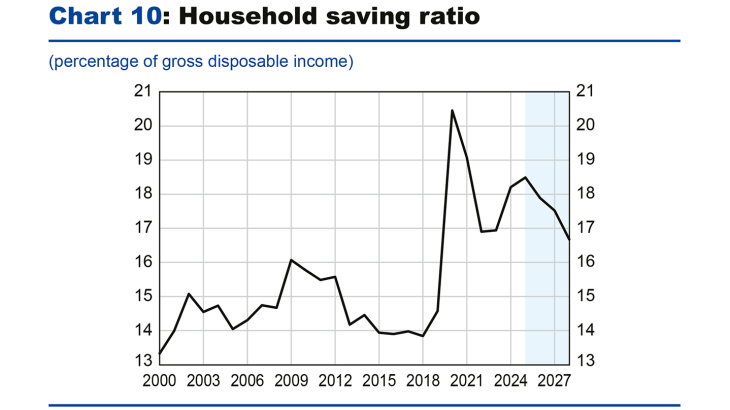

After having risen each year since 2022, the household saving ratio fell slightly in the third quarter to stand at 18.4%, according to the national accounts published on 28 November. Over the whole of 2025, the saving ratio is expected to increase slightly, with household consumption growing even more moderately than purchasing power. At the same time, as total real income is expected to slow in 2026 but real wages and consumption are forecast to be more resilient, the saving ratio should begin to decline, provided that the climate of political uncertainty improves. It should remain above its pre-Covid historical average over the entire projection horizon (see Chart 10). This should notably be due to the fact that property income – which has a particularly low marginal propensity to consume – still accounts for a larger share of total household income. Indeed, this category of income should continue to be underpinned by the upward trend in long-term interest rates, according to Eurosystem assumptions (see Table A).

After contracting sharply by 5.6% in 2024, household investment declined slightly further in the third quarter of 2025 (by 0.1%), driven down by its service component linked to lower real estate transactions. However, several indicators point to an upcoming recovery. First, households’ real estate purchasing power has recovered slightly, buoyed by the observed easing of the cost of credit and the correction and subsequent stabilisation of prices for existing homes since early 2024. In addition, new household loans, which picked up in 2024, have continued to grow in 2025, signaling a recovery in existing home transactions and in real estate-related services. Housing starts are also showing signs of recovery, which should fuel growth in construction investment over the coming quarters. Against this backdrop, household investment is expected to pick up in the fourth quarter, leading to slightly positive growth on average for 2025, before a gradual rebound in 2026 and 2027. However, the upward trend in French 10-year rates in the Eurosystem’s technical assumptions implies slightly less favourable bank financing conditions, which will slow down the recovery in household investment towards the end of our projection horizon.

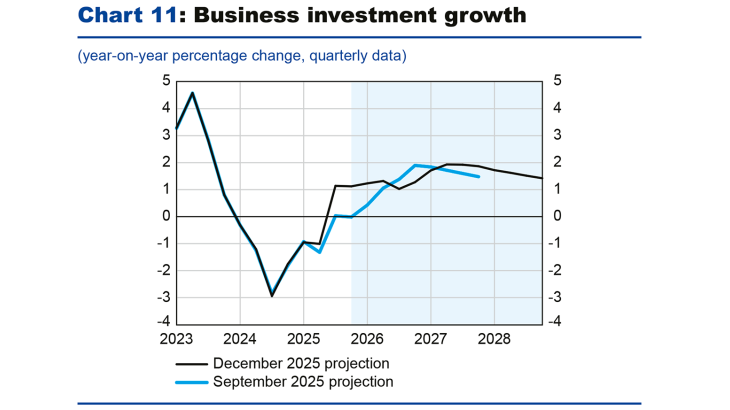

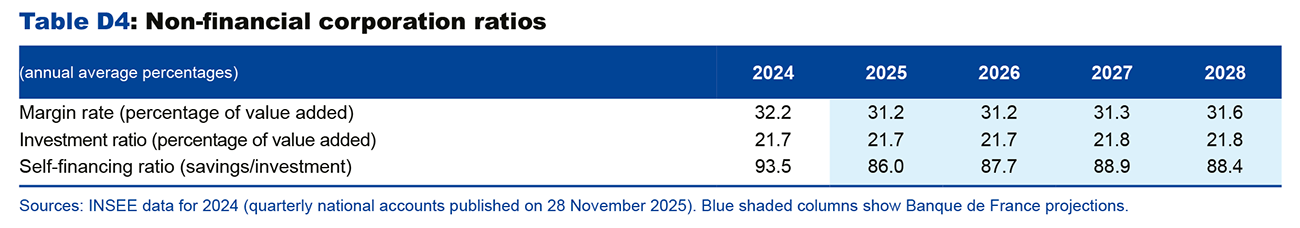

Business investment is expected to gradually strengthen, assuming that tax and fiscal uncertainty declines

After being hampered by still-high financing costs in 2024, business investment recorded a sharp increase in the third quarter (see Chart 11), particularly in information and communication technology. However, in a domestic context marked by high uncertainty (see Box 2) and a decline in credit demand reported in the latest bank lending survey, investment growth is still expected to be moderate until mid-2026, before rebounding as a result of stronger final demand. In the medium term, it should be supported by structural demand related to the digital and energy transitions, as well as by additional spending in the defense sector.

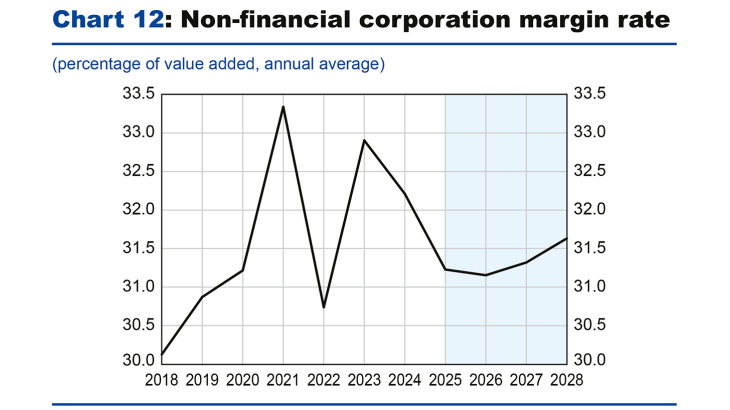

According to the national accounts published on 28 November, the profit margin for non-financial corporations stood at 31.5% in the third quarter of 2025, slightly above its 2019 average (see Chart 12). The margin rate is expected to remain stable in 2026 and 2027, buoyed on the one hand by production tax cuts (business value added tax) provided for in the initial Draft Budget Act for 2026, but penalised on the other by the increases in employer contributions provided for in the Social Security Financing Act (restructuring of general tax breaks and reduction of certain loopholes applicable to wage supplements) passed on 9 December. The rise in the margin rate in 2028 should be due to an accounting mismatch linked to the implementation of the second European Union Emissions Trading System (ETS-2). The self-financing rate should also remain stable, which suggests that companies are able to finance their investments from internal resources.

Note: Businesses include non-financial corporations, financial corporations and sole proprietors.

Reducing the government deficit, which will probably be close to 5% of GDP in 2026, is unlikely to be sufficient to begin stabilising the public debt ratio.

In 2025, the government deficit is expected to come in at -5.4% of GDP, as forecast in the Budget Act. This figure represents an improvement of 0.4 point of GDP compared with 2024 and after two consecutive years of deterioration. This fall in the government deficit should mainly be attributable to tax measures that have pushed up the rate of taxes and social security contributions (+0.8 percentage point of GDP). However, the rise in public expenditure (+0.3 percentage point of GDP, including +0.1 percentage point related to interest payments) and the decline in revenue excluding taxes and social security contributions (–0.1 percentage point of GDP) are expected to limit the improvement in the fiscal situation.

Our projections were finalised on 3 December 2025. In the absence of any budget legislation having been passed at the time of finalising our projections, we used public finance assumptions for 2026 based on the Draft Budget Act and the Social Security Financing Bill presented on 14 October, with a fiscal effort driven by both new tax measures and a control of public spending. Under these assumptions, the government deficit would have been reduced to just under 5% of GDP. On 3 December, the French National Assembly passed a Social Security Financing Act with a higher level of spending than the initial version. As a result, the government deficit in 2026 could be around 5% of GDP, assuming that the initial Draft Budget Act is passed. However, it is also possible that the Draft Budget Act will not be passed within the required timeframe. In this case, a special law could be adopted, which would authorise the government to roll over its spending and collect existing taxes in 2026. Such a fiscal situation, comparable to that observed at the end of 2024 and the beginning of 2025, could be temporary, if a Budget Act is adopted later in 2026.

It is therefore likely that the 2026 deficit will ultimately be worse than our fiscal assumptions. However, this would not lead to significant surplus growth for 2026. The effect on GDP of fiscal consolidation that is less than that provided for in the Draft Budget Act/Social Security Financing Bill for 2026 would probably be offset by the wait-and see attitude of households and businesses due to prolonged fiscal uncertainty.

Beyond 2026, the fiscal assumptions used for strictly conventional purposes assume a primary structural adjustment of 0.6 percentage point of potential GDP in 2027 and 2028. Under these assumptions, the public deficit ratio would continue to decline in 2027 and 2028. However, this adjustment is less than that underlying the multi-year trajectory set out in the Draft Budget for 2026 (0.9 percentage point in 2027 and 2028), which is based on savings that are not yet sufficiently detailed to be included in these projections.

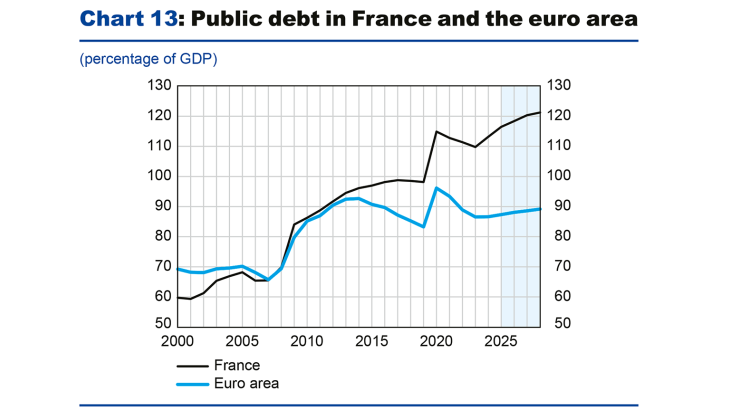

In the absence of additional measures, the fiscal adjustment assumed in our scenario would be insufficient to stabilise public debt as a percentage of GDP by 2028. This ratio is expected to increase over the entire projection horizon and stand at just over 120% of GDP in 2028 (see Chart 13). This would widen the gap with the euro area as a whole, where the debt ratio is expected to be close to 90% of GDP in 2028 .

Risks to economic activity are broadly balanced and rather on the downside for inflation

A considerable number of uncertainties are still weighing on French growth. At the international level, US trade policy remains a source of uncertainty, even if it has diminished. Added to this is the risk of a correction in the valuations of US companies linked to artificial intelligence (AI), which could spread to European markets. Conversely, the better-than-expected resilience of the global economy and the potentially faster-than-expected effects of AI could provide further support for economic activity in France.

At the domestic level, political and fiscal uncertainty remains high, raising questions about France’s fiscal and tax trajectory and its ability to stabilise the public debt ratio. This situation could lead to a further widening of the spread on French sovereign bonds, which would heighten financial vulnerability and weigh on the confidence of economic agents. It could also prolong – or even accentuate – the wait-and-see attitude of households and businesses, which would result in particular in a less marked decline in the saving ratio than that recorded over the projection horizon. Conversely, the surprise on the upside for activity in the third quarter and our latest economic indicators show that activity in France has so far been more resilient than expected in the current context.

As regards inflation, the risks are rather on the downside. As indicated in the section on inflation, the abandonment of the measures to double flat-rate contributions and medical deductibles leads us to lower our inflation forecast for 2026. In addition, increased competition from Chinese exports on the European market could generate disinflationary pressures, as could a further appreciation of the euro against the dollar and the yuan. In addition, diplomatic progress in the Ukrainian conflict could lead to an easing of gas and oil prices. Conversely, upward pressure could come from meat prices, which have risen sharply over the past year and could continue to rise should the wave of epidemics continue. Lastly, increasing disruptions to production chains, caused by geopolitical tensions, also pose an upside risk to industrial goods prices.

Box 1

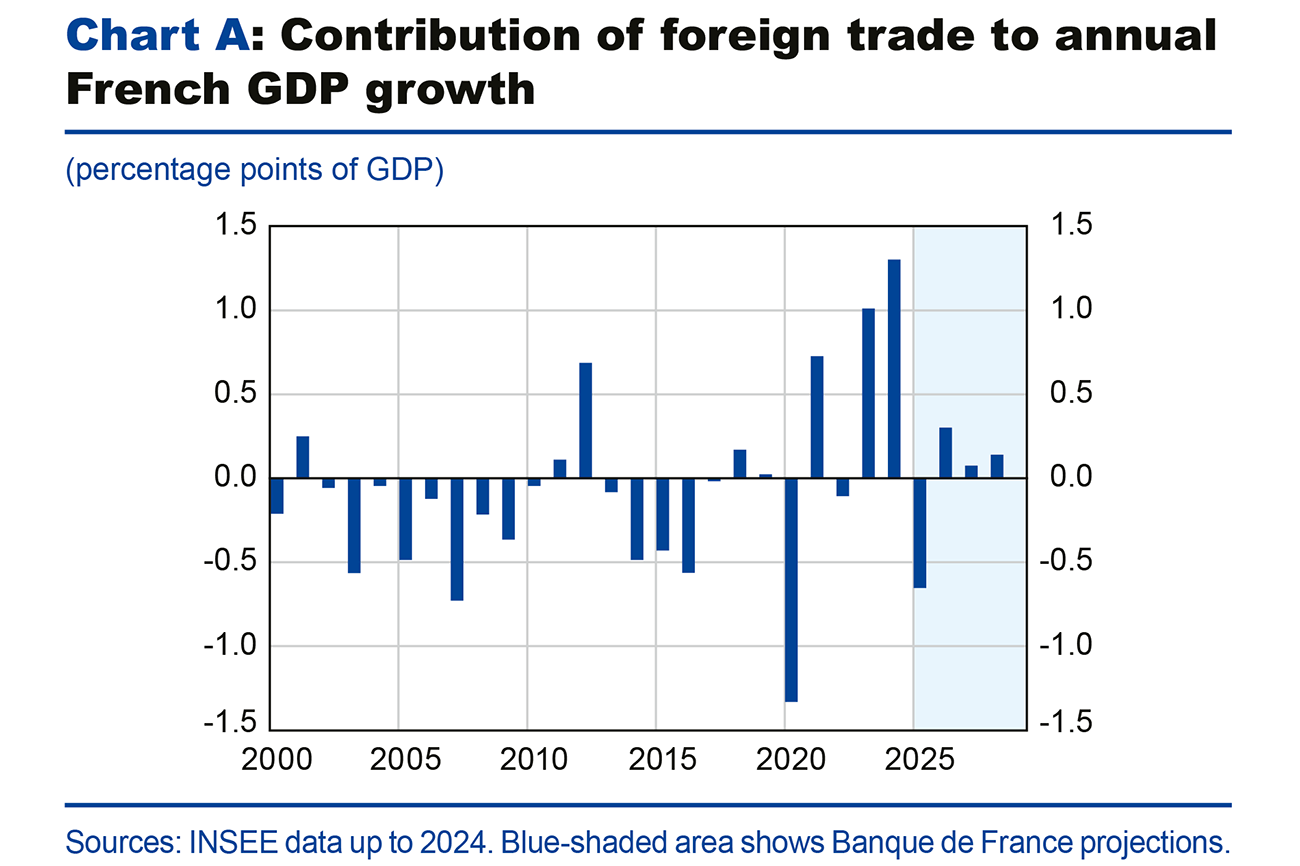

The contribution of net foreign trade (exports minus imports) to French growth has been highly volatile in recent years (see Chart A), against a backdrop of non-stop crises: the health crisis, Russia’s war in Ukraine, political uncertainty and hikes in US tariffs. However, the latter factor only had a limited effect on French exports, due in particular to exemptions for the aeronautics sector.

In 2023 and 2024, foreign trade made a major contribution to GDP growth (i.e. 1.3 percentage points) thanks to strong momentum in exports and a recovery of export market shares together with a contraction in import volumes in 2024. This was the result of sluggish domestic demand, particularly for private investment, against a backdrop of tighter financial conditions. Measured by product type, net exports of energy and manufactured goods, excluding transport equipment and agri-food products, made the largest contribution to GDP growth (see Chart B). After weighing negatively in 2023, net exports of services, excluding tourism, also helped to drive GDP growth in 2024, particularly financial services, transport services and business services.

Nevertheless, France’s market share has not returned to its pre-Covid levels (see Chart C). Beyond the cyclical impact of the Covid crisis, France is experiencing a structural erosion of its market share in favour of emerging economies, including China (for an analysis of intermediate services in particular, see Fact Sheet No. 2 of the 2024 Annual Balance of Payments Report published in July 2025).

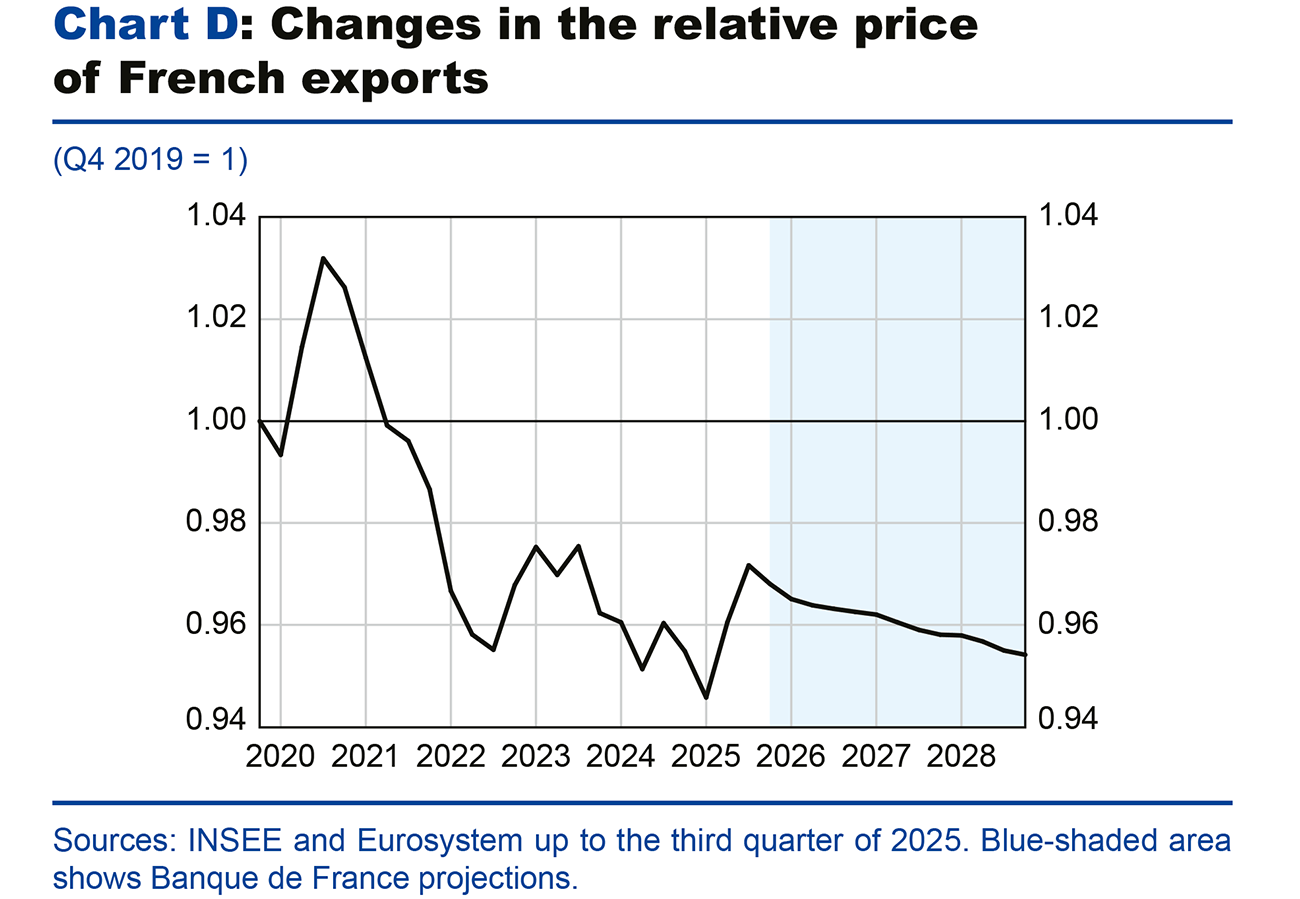

In this forecast, we do not anticipate a return of French market shares to pre-Covid levels, but rather a stabilisation at second-quarter 2025 levels, once the see-saw effects related to transport equipment have fed through. French market shares should be buoyed by positive factors, notably gains in competitiveness over the projection horizon, thanks to a decline in the relative price of French exports, despite the appreciation of the euro in 2025 (see Chart D). Furthermore, French aeronautics exports are expected to continue to underpin growth, assuming that production rates are sufficient to

meet well-stocked order books. Conversely, other traditional drivers of French trade could experience a more mixed picture, particularly agricultural and agri-food products, for which the trade surplus has declined in recent years, and the luxury goods sector, which could suffer from the increase in non-tariff barriers. Moreover, competitive pressure from emerging economies, which also involves non-price competitiveness factors (a shift towards higher value-added products), is expected to increase over the projection horizon, automatically weighing on French market share (see “The evolution of China’s growth model: challenges and long-term growth prospects”, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5/2024).

Imports have been revised downwards over the projection horizon when compared with the September forecast, as a result of the recent re-estimation of our forecasting model, which makes imports a function of final demand, effective exchange rates and a new global indicator of product variety. All in all, after weighing heavily on GDP growth in 2025, net exports are expected to make a positive contribution to growth between 2026 and 2028, thanks in particular to foreign demand for French goods in excess of domestic demand, which, all other things being equal, should result in exports outpacing imports.

Box 2

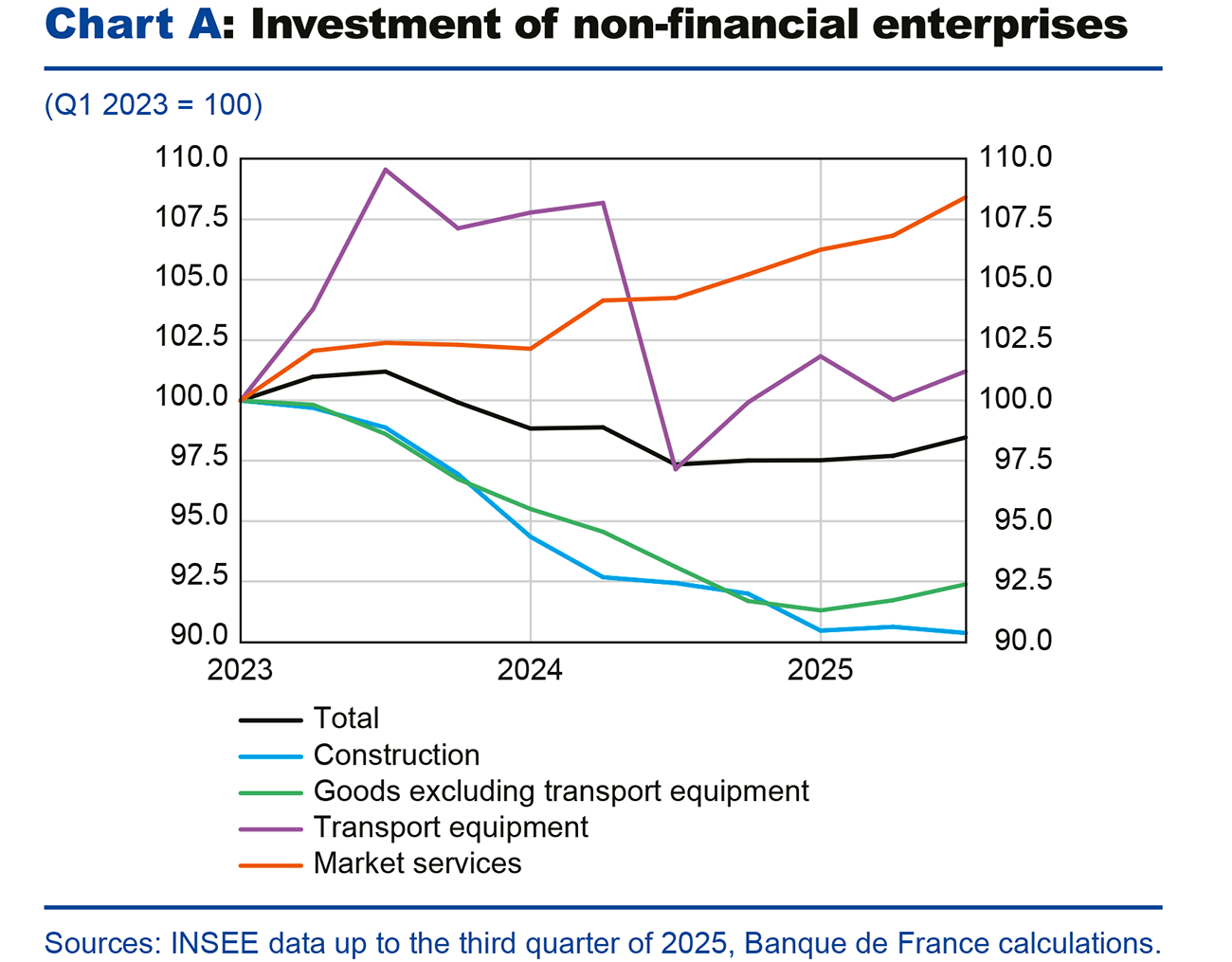

Business investment, including that of financial corporations and sole proprietors, declined by 1.6% in 2024, due in particular to higher financing costs and to slowing final demand. Since mid-2024, it has fluctuated significantly due to opposing forces. Final demand remains weak and uncertainty over fiscal policy has increased since the dissolution of the French National Assembly in June 2024, while uncertainty over trade policy remains somewhat high. Conversely, the cost of capital, which had been rising sharply since 2022, has declined since the end of 2024. In the third quarter of 2025, business investment surprised on the upside (+0.7%), driven by strong investment in services by non-financial enterprises.

The aggregate momentum is accompanied by a sectoral divergence, which takes the form of a “K”-shaped curve (see Chart A). Investment in services, which had been dynamic since the 2000s, picked up after the Covid period (up 8 percentage points since early 2023), supported by the information and communication sector and, in particular by computer programming and software publishing. Conversely, investment in goods, excluding transport equipment, and in construction has been declining since 2023 (by 7.6 and 9.6 percentage points respectively).

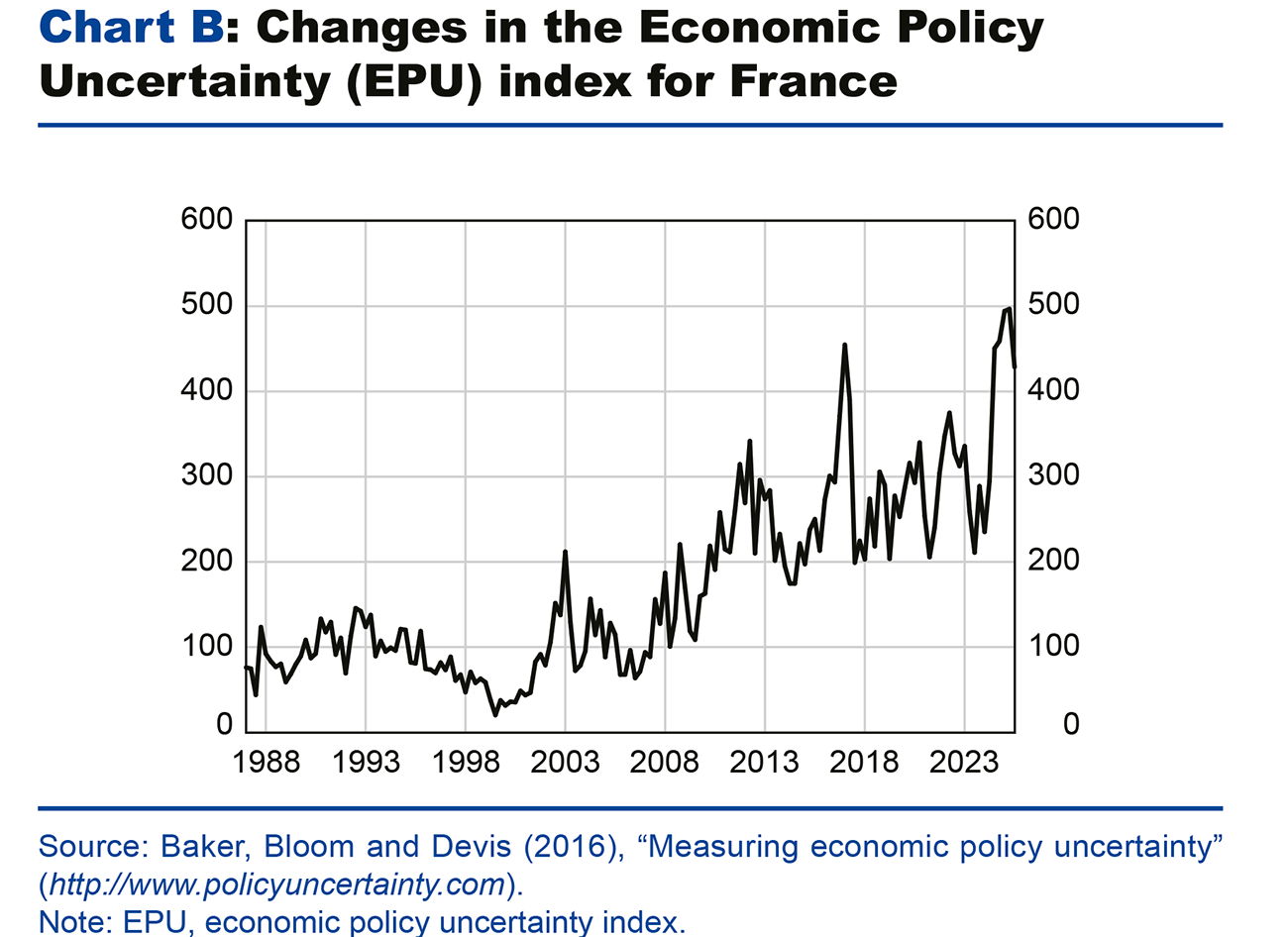

This divergence may have been amplified by the climate of fiscal uncertainty in recent years. The Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) index developed by Baker, Bloom, and Davis (2016), applied to France, provides a measure of this uncertainty. This indicator, which is based on text analysis techniques, measures the proportion of articles, in a sample of newspapers, that simultaneously contain terms associated with uncertainty, politics, and economics. It rose sharply from mid-2024 onwards, following the dissolution of the French National Assembly, and has remained at a high level since then (see Chart B).

In this context of high uncertainty, companies may adopt a wait-and-see attitude (Pindyck 1991 1, Bloom 2009 2), considering that it is less costly to postpone an investment project than to adjust it later. This wait-and-see attitude may result in a decrease in investment. Furthermore, it could also exacerbate the sectoral divergences observed. Because of its intangible nature and faster depreciation, investment in services would be more easily reversible and less adversely affected by increased uncertainty, while investment in goods and in construction would be riskier.

In order to estimate the impact of uncertainty on business investment, we use a vector autoregressive (VAR) model containing investment, which in particular places the EPU France index first in the list of variables (and is thus considered as exogenous). We estimate that uncertainty has already had an effect of around 0.9 percentage point on aggregate business investment, representing around -0.1 percentage point of GDP in 2025.

Assuming that the current level of political uncertainty gradually decreases between now and the end of 2026, business investment would still decline by around 0.3 percentage point on average over the whole of next year. It could nevertheless start to pick up during the year thanks to the acceleration in final demand. However, if uncertainty were to increase again or prove more persistent than expected, it would continue to weigh on business investment and could hamper its recovery.

1 Pindyck (R. S.) (1991), « Irreversibility, uncertainty, and investment », Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 29 (3), p. 1110-1148.

2 Bloom (N.) (2009), « The impact of uncertainty shocks », Econometrica, vol.77 (3), p. 623-685.

Appendix A: Eurosystem technical assumptions

Appendix B: Key year-end projections for France

Appendix C:

Appendix D:

Download the full publication

Updated on the 14th of January 2026