- Home

- Governor's speeches

- «Credible but not static: in praise of m...

«Credible but not static: in praise of monetary agility»

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 19th of June 2025

EMU Lab, Florence – 19 June 2025

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am delighted to be in Florence and I wish to warmly thank Marco Buti for the invitation.

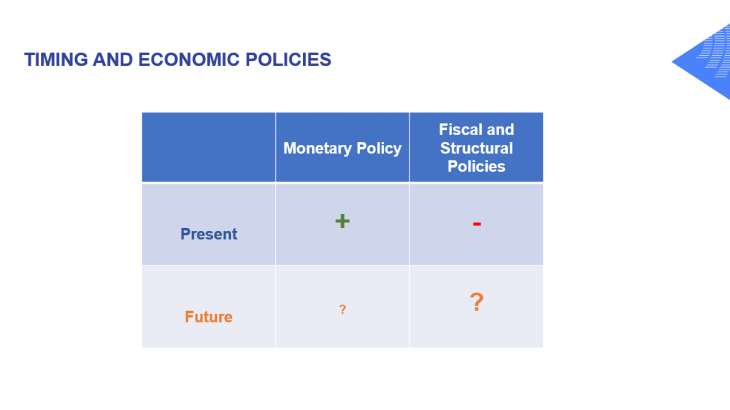

If an observer were to look only at the current macroeconomic data - and in particular the sustained convergence of headline inflation to our target of 2% - it might occur to him or to her that economic stability has been achieved… but on closer inspection, it is certainly not guaranteed for the future. This is the paradox I will explore with you today, using this simple chart that combines two dimensions: time and the scope of economic policies.

I will come back to the left-hand column. But I want to stress the obvious: the other economic policy levers are not working well today. This is because we have overused the fiscal instrument through past crises (Covid, inflation) and, asymmetrically, we are correcting this too slowly today, from the United States to my own country. Conversely, we have not sufficiently promoted structural reforms for growth and productivity. The other obvious point is that unpredictability is peaking for the future, notably due to the policy shift by the new US administration. Europe knows how it should respond to seize its moment, thanks to the Letta and Draghi reports. I commend them, here in Italy. A quarter of a century after our monetary sovereignty, we must now ensure our economic and financial sovereignty. But so far, Europe’s reaction is too slow and too weak: I call for a mobilising date, as Jacques Delors did with January 1, 1993, for the single market, for example 1 January, 2028i. As a nice saying goes: “The difference between a dream and a project is a deadline” [“La differenza tra un sogno e un obiettivo è una data di scadenza”]. Monetary policy cannot do everything, and the euro area must not resign itself to being trapped in a state of controlled inflation but sluggish growth.

Today, I will focus on the two boxes on the left, and delve into two conundrums with you:

- Why the current monetary situation is credible, but not static (I).

- Why the monetary policy of tomorrow must therefore be agile, while remaining predictable (II).

I. Credible but not static? The “2 and 2”

1.1 The current situation is satisfying…

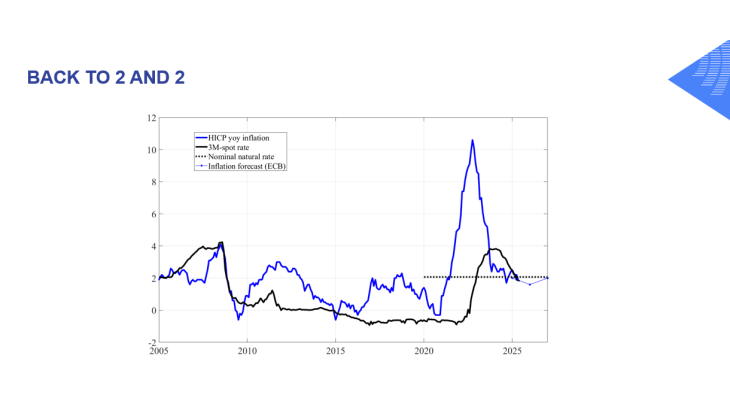

Allow me to start with the obvious: inflation has been successfully brought back to target and this is excellent news. We are now in a good position in the euro area (EA), with inflation at 1.9% in May and forecast at 2.0 % for this year on average. Hence, our Governing Council, around President Lagarde, decided to cut the deposit facility rate to 2% at our meeting two weeks ago. Our latest projections show that we shouldn’t fear in Europe, contrary to the US, an inflationary effect of tariffs. With this latest decision, our short-term policy interest rate is very close to the centre of estimates of the nominal neutral rate.

This “2 and 2” scenario of inflation close to target and policy close to neutral feels like back to normality, after nearly a contrasted decade, sequenced first with below target inflation and recourse to a number of non conventional monetary policy instruments, followed by an opposite phase with the largest inflationary shock in decades and an inverted yield curve. Back to normal is a very positive step; nevertheless, in still abnormal times, it does not necessarily mean an end to the journey.

Sources : ECB, Banque de France computations

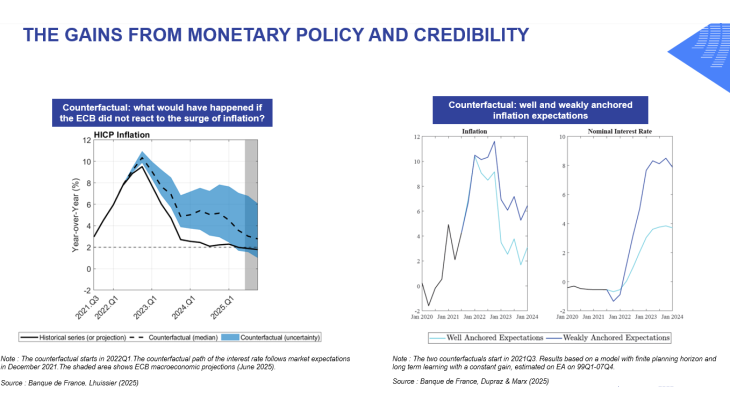

This return to 2% inflation is also highly satisfying as the disinflation from the peak of 10.6% in October 2022 was much less costly in terms of output and employment than feared. The unemployment rate is at its lowest level since the launch of the euro, at 6%. Thanks to the credibility of the Eurosystem, this time, the effects of commodity price shocks quickly faded away and their propagation to core inflation was quite limited because medium-term inflation expectations remained broadly stable, providing a solid “anchor" to prices and wage-setting.

Source : Banque de France, Lhuissier (2025)

2-Note : The two counterfactuals start in 2021Q3. Results based on a model with finite planning horizon and long term learning with a constant gain, estimated on EA on 99Q1-07Q4.

Source : Banque de France, Dupraz & Marx (2025)

As I have discussed in recent speechesii, Banque de France researchiii suggests that, had inflation expectations been as poorly anchored as they were in the 1970s in the US, our policy rates would have had to peak around 8% instead of 4%. This central bank credibility doesn’t come out of the blue. When politicians undermine central bank independence, they put in peril this credibility that allows central banks to stabilise inflation at a lower cost.

1.2… but not static

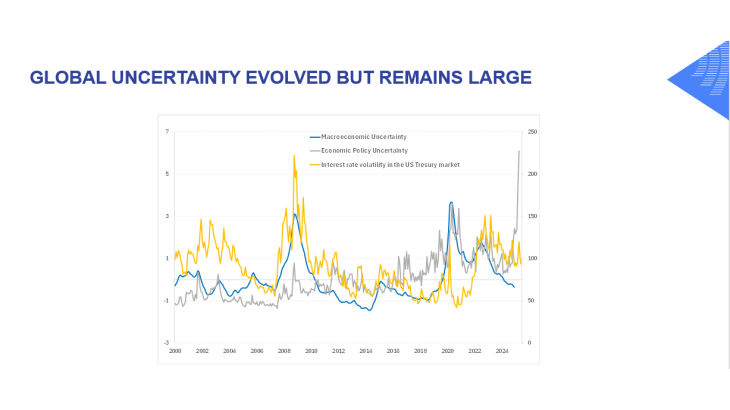

But this return to “2 and 2” should not give way to complacency and passivity. China’s mercantilism and the current US administration’s erratic tariff policy have severely undermined the rules-based international trading system. In addition, global bond markets seem increasingly worried by public debt sustainability in the US and across the world, and we already see signs of tensions at the very long end of yield curves, with the risk of international spillovers.

Sources : Bloomberg, Jurado et al. (2015), Baker et al. (2016)

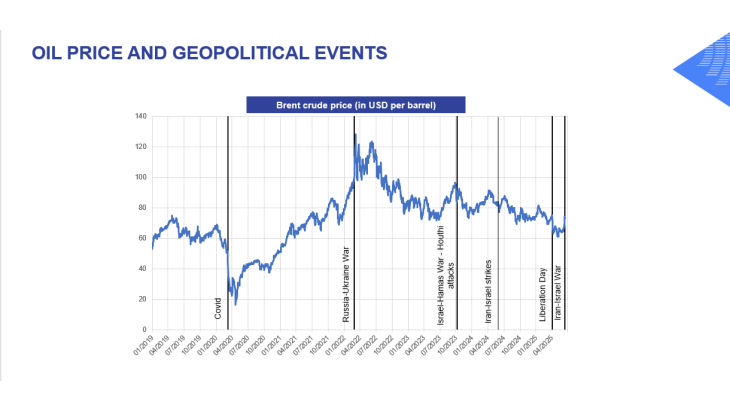

Furthermore, as we could see once again since Thursday, oil price strongly reacts to dramatic geopolitical events.

It’s now back to its pre “Liberation day” level, but still far below the 2022 level, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. We will monitor closely the possible spillovers of energy prices. If ever these consequences happened to be lasting and propagating – i.e. affecting underlying inflation and inflation expectations –, we could possibly adapt our monetary policy: to put it short, no automatic monetary reaction, but “monetary agility” on which I will elaborate further.

Over the longer term, other supply shocks are likely to occur more frequently. Extreme climate events are also likely to disrupt supply chains. Information technologies are developing at a fast pace, with AI and quantum computing likely to be the next technological shocks that will possibly increase productivity. More frequent supply shocks will not mean per se higher inflation, but very probably a more volatile inflation, which could weaken the anchoring of inflation expectations.

Because the current equilibrium is unstable, we must above all avoid being complacent. As we have now entered a territory close to the neutral stance, the natural rate R* becomes a less meaningful guidepost. The debate is no longer about navigating by the “stars” to wonder whether we are restrictive or accommodative. It is about how to temper volatility in a world of uncertainty. Here agility and laying out a clear reaction function play a crucial role.

II. Agile but predictable

Fair enough about agility, and nobody would recommend rigidity. But let us acknowledge that it raises two serious questions.

a/ Agility does not mean that we should rush to come back to the 2% target at short notice, in case of inflation volatility. We have a medium-term orientation around our symmetric objective, which implies we do not have to respond to deviations from target at one point in time. Instead, we have to react to dynamics that risk pushing inflation off target: what matters is whether a deviation from target is more likely to increase or to decrease . And medium term means within our projection horizon.

b/ Agility should not imply that we are unpredictable or indecisive. In the past, when we had strong forward guidance, our actions were described as being on "autopilot”. Today, we are sometimes accused of the opposite – "flying blind" or making "ad hoc decisions." I do not believe we are doomed to wander between these two extremes: it is time to return to a concept that has been less used in recent years – the central bank reaction function. We need to clearly state not what we will do, but how we think and will act, in a “readable” way.

2.1 The central bank reaction function

What is the Eurosystem reaction function? Since 2023, our reaction function has been based on three criteria: the inflation outlook; trends in underlying inflation; and the transmission mechanism.

When inflation was surging and monetary policy was tightening rapidly, it was natural that the second and third criteria were emphasized. With high uncertainty about the inflation outlook, it was important to ensure that inflation expectations did not become deanchored and the underlying inflation criteria was this backstop.

Likewise it was important to assess how quickly changes in policy rates were transmitting to borrowers and ultimately to the demand and supply of credit.

Indeed, the transmission lags have been at least as swift and satisfactory in this latest cycle as in previous ones: each rise in the deposit facility rate (DFR) was almost fully transmitted to bank loans to businesses and households within a year. Loan volumes in the euro area weakened sharply starting from the end of 2022, with a peak response 18 months after a rate hike. However, we must remain vigilant today to the broader transmission of monetary policy actions to financial conditions. In particular, we need to be careful that international spillovers via higher term premia in long term yields and the exchange rate do not counteract the desired monetary stance. I will come back to it.

Inflation projections and the use of scenarios

That said, now that inflation has returned to target, with inflation expectations well anchored, we can put more weight on the first criteria, the inflation outlook.

But inflation projections rely on various assumptions. Developing scenarios and applying informed judgment about possible future outcomes can assist policymakers. But scenario analysis is no panacea. First, we can only analyse in detail a few scenarios at a time, in practice one or two as we did early June with a severe and a mild scenario on trade. We will inevitably overlook certain shocks that do appear. Second, it might be difficult to assign probabilities to scenarios and therefore to use them for policy risk management, especially in periods of ‘Knightian’ uncertainty – not quantifiable.

Theoretically appealing approaches, like model averaging, are difficult to apply in practice. Instead, we could consider methods inspired by robust control. Specifically, robust control aims at avoiding the worst possible outcome, for example easing monetary policy exaggeratedly when an inflationary shock materializes. But this leads to making decisions and ruling out options based on hypothetical scenarios, irrespective of their likelihood. So scenarios will be an important aid to decision-making but should be used judiciously rather than systematically: not in all occurrences of ECB forecasts, and subject to discretion rather than rules in their policy implications.

Three principles of monetary agility

Given all this, let me give you several thoughts on what agility means:

- Speed of assessment. In rapidly changing circumstances or complex shocks, there is always the temptation to wait for additional data to obtain a fuller picture. To be agile is to do this analysis faster by exploiting new real-time data sources, incorporate new models from the latest research, survey new staff analyses on risks and contingencies, and avoid the excess of group thinking. For example, our analysis of the effects of tariffs have benefited from using daily shipping data and freight prices.

- Symmetric and state-contingent policy paths. We rightly stress that our monetary action should be as “persistent and forceful” as needed . But is there a contradiction between persistence in policy and agility? No, not if signals are understood to be state-contingent and we avoid being boxed in. If the state changes then so does the policy, including possibly its symmetric direction both ways. Persistence is only relevant in certain states of the world.

- Acting not stronger but sometimes faster. And what about a forceful response? If required, it is not compulsory to go in incremental steps. Of course, in the presence of new shocks, central banks may prefer a wait-and-see attitude, in line with Brainard's principle of mitigationvi : if the effects of policies are uncertain, it is better to react less. But, conversely, waiting too long for events to materialize can result in substantial losses. The Banque de France research paper entitled “The pitfall of cautiousness in monetary policy” has shown that this attitude can lead to a cautionary bias that undermines inflation expectationsvii. This may imply shorter and swifter interest rate cycles, although any adjustments still have to be orderly.

2.2 What should we do now?

High uncertainty surrounding the global economic outlook obviously calls for humility about our ability to predict future inflation and monetary action. Our primary duty today is to assess risks. I mentioned earlier oil prices, while avoiding to draw automatic monetary conclusions. Overreacting, or conversely systematically “looking through”, would be contrary to the necessary agility. We should monitor at least two other sets of data:

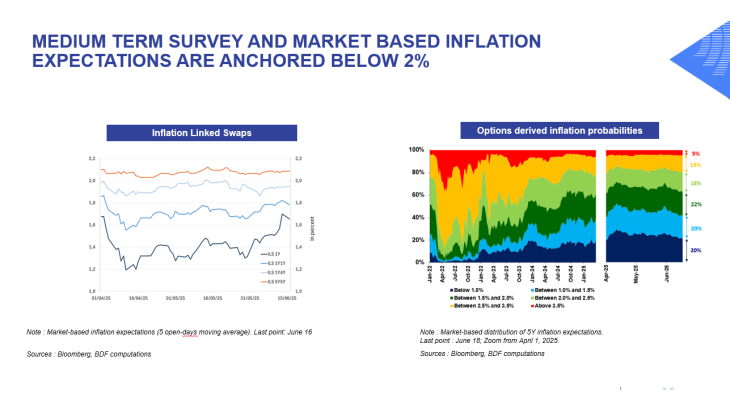

- Do inflation expectations reflect a risk of lasting spillover? They don’t, so far, as medium term market based measures of inflation expectations have recently remained clearly below 2% in 2026. The probability that inflation falls below 1.5% in 5 years is around 40% according to the pricing of options on inflation.

Sources : Bloomberg, BDF computations

2- Note : Market-based distribution of 5Y inflation expectations.

Last point : June 18; Zoom from April 1, 2025.

Sources : Bloomberg, BDF computations

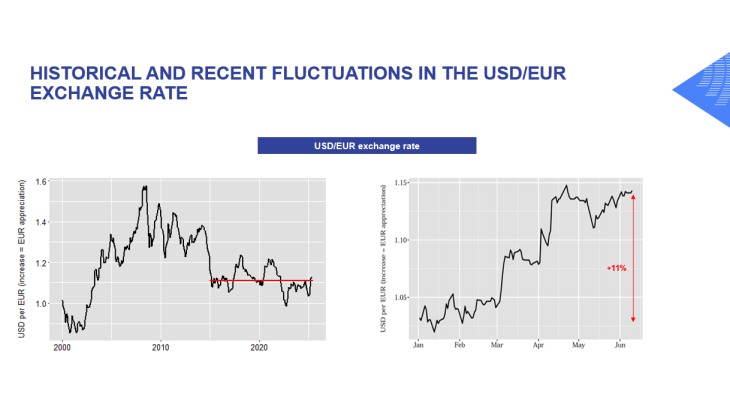

How is the exchange rate of the euro evolving? Since early 2025, the euro has appreciated by 11% against the US dollar: this came a bit as a surprise, and a sign of increasing relative confidence towards Europe. Obviously, we have no target for the exchange rate, and the last decade since 2015 has seen a striking diminution of volatility of the pair.

Source : ECB; Banque de France calculations

That does not nevertheless mean any “benign neglect” on our side: the recent appreciation of the euro has a clear disinflationary effect. According to our elasticities, its magnitude, for a 10% appreciation, would broadly compensate the inflationary effect of a possible 10 EUR increase of the oil price – which we are still quite far from as of today.

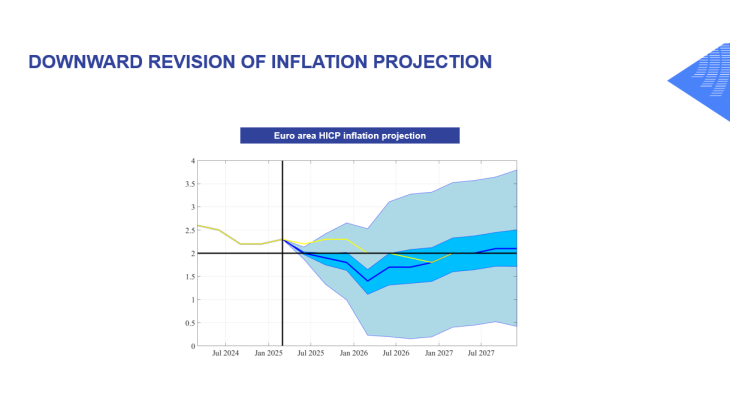

From today's perspective, the risk of undershooting our 2% inflation target is perceived by markets as greater than that of overshooting. In the June projections, headline inflation is indeed seen to fall below 2% in the second quarter of 2025 and to continue to decline into early 2026, with a trough of around 1.4%.

Sources : ECB

This decline would be driven by all the main components, not only energy but also core inflation, resulting from low wage growth and weak demand. The projected increase in headline inflation to 2.0% in 2027 is amplified by a temporary upward impact from energy inflation, reflecting the introduction of the new Emissions Trading System (ETS2). This measure is desirable but far from certain both in its timing and modalities.

In such a context, we need to remain alert and agile, in all our next meetings. As Voltaire said “Le doute n'est pas un état bien agréable mais l’assurance est un état ridicule viii” [“doubt is not a very pleasant state, but certainty is a ridiculous one”]. With this due wisdom, let me only give two possible landmarks:

(i) a neutral rate and a terminal rate are two different animals. They can happen to be in the same position, but they are not identical by nature.

(ii) the current assessment suggests that, barring a major exogenous shock, including possible new military developments in the Middle East, if monetary policy were to move in the next six months, it could be more in the direction of accommodation.

Conclusion

According to a great Florentine, Niccolò Machiavelli, two forces shape the course of events: fortuna and virtù. Fortuna, or fate, stands for the unpredictable shocks that affect us – geopolitical tensions, technological disruptions, and other external forces beyond our control. Virtù, or courage, by contrast, reflects our ability to act with determination, to adapt, and to anticipate. In a context of heightened uncertainty, the tension between stability and volatility puts our monetary policy stance to the test. But through virtù – our capacity for clear-sighted and agile action – we can secure lasting success. Monetary policy can, along the principles suggested, remain not only agile, but also predictable and “readable”. Striking this balance, we ensure that, with the highest ever confidence (at 83%) of our fellow European citizens, the euro remains ready to navigate an uncertain future.

iElderson, F. (2025). Brussels. Europe at a crossroads: it is high time to complete the Single Market, 18 June.

iiVilleroy de Galhau, F. (2024) “A Monetary Policy Perspective: Three lessons from the recent inflation surge”. Speech at New York University. 22 October.

iiiDupraz, S. and Marx, M. (2025) The benefits of well-anchored inflation expectations. March.

ivVilleroy de Galhau, F. (2024) Monetary Policy in Perspective (II): Three landmarks for a future of “Great Volatility”. Speech at the London School of Economics. 30th of October.

vAs noted in our Monetary Policy Strategy Statement of 2021

viBrainard, W. C. (1967). Uncertainty and the Effectiveness of Policy. The American Economic Review, 57(2), 411–425.

viiDupraz, S., Guilloux-Nefussi, S. and Penalver, A. (2023): ‘A Pitfall of cautiousness in Monetary Policy’. International Journal of Central Banking, vol. 19(3), pages 269-323, August

viiiVoltaire (1770), Letter to Frederick William, Prince of Prussia, 28 November.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 24th of June 2025