- Home

- Governor's speeches

- A Monetary Policy Perspective: Three le...

A Monetary Policy Perspective: Three lessons from the recent inflation surge

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 22nd of October 2024

New York University – 22 October 2024

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau,

Governor of the Banque de France

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure to be in New York and I am grateful to Thomas Philippon for his invitation. My theme today will be what first lessons we can learn for monetary policy from the surge and then decline in inflation. In the euro area, inflation reached 10.6% in October 2022 and exceeded 4% for two years. But inflation was as rapid to decline and now, at 1.7% in September 2024, stands very close to our target of 2%.

Since Ben Bernanke’s speech in 2004 (Bernanke (B.),« The Great Moderation », Remarks at the meetings of the EEA, 20 February 2004), there is always a debate about whether favourable outcomes are good luck or good policy. And this time we have had a dose of good fortune.

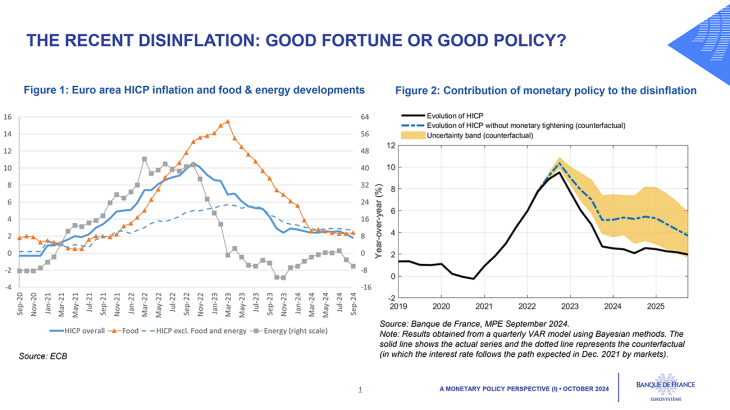

As shown in Figure 1, energy and food prices contributed to inflation developments both uphill and downhill. But the return of inflation to 2% and its speed of convergence are also due to our monetary policy. Banque de France estimates shown in Figure 2 suggest that HICP inflation would have been between 2.5% and 3% higher in 2024 without monetary tightening, in line with ECB estimates (Lane (P.), « The analytics of the monetary policy tightening cycle », Guest lecture, Stanford, 2 May 2024). These estimates are even conservative as they do not include the effect on the anchoring of long-term inflation expectations.

In taking stock of what we have learned during this episode, let me focus on three dimensions: monetary policy and disinflation ; monetary policy and growth ; monetary policy and its instruments.

Monetary policy and Disinflation: No magic, but a virtuous circle between past & present credibility, and between communication & action

The relatively low cost of disinflation has not been a given. Not so long ago, many observers were claiming that inflation would either proved persistent (including in the ‘last mile’) and/or be eradicated only at the cost of a recession. Why were they proven wrong so far?

A tale of two disinflations: contrasting economic paths

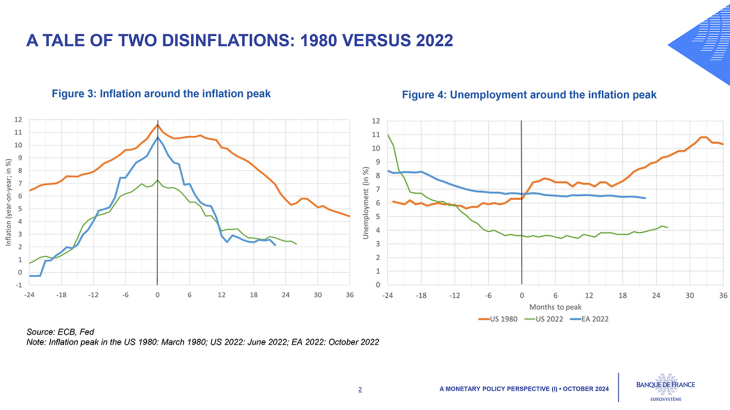

Let me start with a tale of two disinflations: the great disinflation at the beginning of the 1980s in the US and the recent disinflation. In both cases energy prices contributed initially to inflation. Crucially, the consensus about the optimal monetary policy response to inflation was largely shaped by the 1980s’ US experience and the subsequent large academic literature (See among others: Clarida (R.), Gali (J.), Gertler (M.), “The Science of Monetary Policy: A New Keynesian Perspective,” Journal of Economic Literature, December 1999; Stock (J.H.), Watson (M.W.), “Has the Business Cycle Changed and Why?”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2002, Volume 17, January 2003; Goodfriend (M.), King (R.G.), "The incredible Volcker disinflation", Journal of Monetary Economics, July 2005). The end of the great inflation from 1980 to 1985 proved that monetary policy was a potent instrument to achieve price stability, but to be credible had to risk high unemployment. As a consequence, the post-Volcker consensus was that central banks (i) should react swiftly and strongly to inflation, as in the celebrated Taylor principle that the interest rate should respond by more than one-for-one to inflation to prevent uncontrollable inflation path, (ii) would need to actively increase unemployment to disinflate the economy, along the Phillips curve, and (iii) should be more independent following a seminal article by Barro and Gordon in 1983 (Barro (R.), Gordon (D.), “Rules, Discretion and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 12: 101-22, 1983).

The recent fall in inflation has been more rapid and less costly in terms of growth and employment than in the 1980s, see Figures 3 and 4 (Villeroy de Galhau (F.), Anatomy of a fall in inflation: from a successful first phase to the conditions for a controlled landing, speech, 28 March 2024). Why the difference? A convincing answer by Goodfriend and King is that most of the high recessionary cost of the Volcker disinflation was due to the Fed’s “imperfect credibility” (Goodfriend (M.), King (R.G.), "The incredible Volcker disinflation", Journal of Monetary Economics, July 2005). Much of the battle Volcker had to fight was against persistently high inflation expectations, a legacy of the loss of control in the 1970s.

This time, central bank credibility led the effects of commodity shocks to prices “to mostly and quickly fade away” as emphasized by Bernanke and Blanchard (2024)(Bernanke (B.), Blanchard (O.), Analysing the inflation burst in eleven economies, 2024).

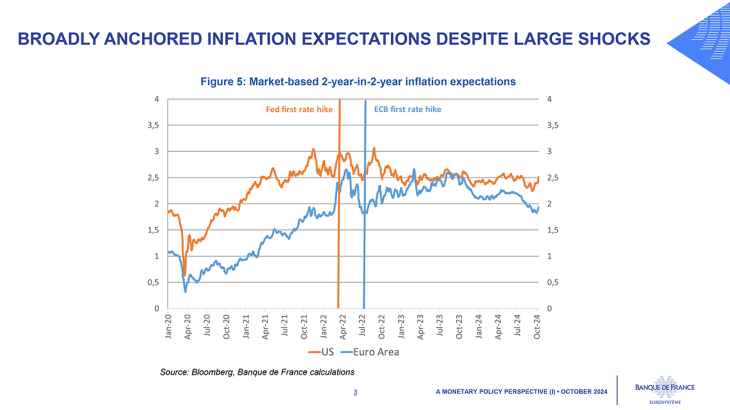

Figure 5 shows that inflation expectations remained broadly anchored despite large shocks, especially after the first rate hike. The question was not if inflation would converge to target but when. This credibility doesn’t come from nowhere but from (a) independence, (b) simple and transparent objectives (inflation targeting), and (c) decisive past actions. Central banks nevertheless also had to ‘walk the talk’. Credibility is an asset to be preserved, not an inheritance to be exploited. In the case of the ECB, our monetary policy responses were forceful and persistent: from July 2022 to September 2023, we raised our key interest rates by 450bps.

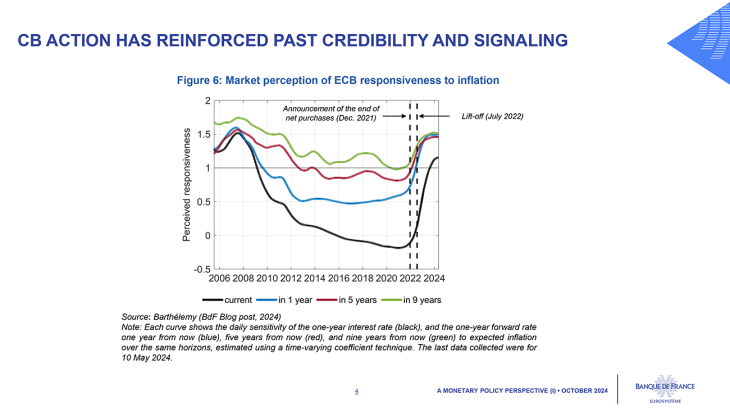

As shown by Bauer et al (2024)(Bauer (M.), Pflueger (C.), Sunderam (A.), “Perceptions about Monetary Policy”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming) in the US case and apparent in Figure 6 from Banque de France work on the euro area (Barthélemy (J.), “Market perception of monetary policy responsiveness”, Banque de France Eco Notepad, 8 July 2024), the market perception of ECB responsiveness – here measured as the time-varying sensitivity of expected rates to expected inflation at the same horizon – has always been strong (higher than one) at long horizons. It suggests that markets anticipate an active reaction function in the medium- to long-run, and this sensitivity increased during the lift-off period from mid-2022 to mid-2023 at all horizons, suggesting that actions reinforced our credibility to fight inflation.

From the vicious circle of inflation to the virtuous circle of credibility

What we learned from the Volcker period is that disinflation is costly and long to achieve for an imperfectly credible central bank. Firms anticipating increasing costs are likely to increase their prices and workers anticipating increasing prices fight for higher wages leading to a vicious inflation circle and creating a strong correlation between current and expected inflation. Imperfectly credible central banks must hence react more forcefully and swiftly. The induced much higher real rates may however quickly cause unemployment but without any immediate gains from price stability, such as lower long-term inflation risk premia.

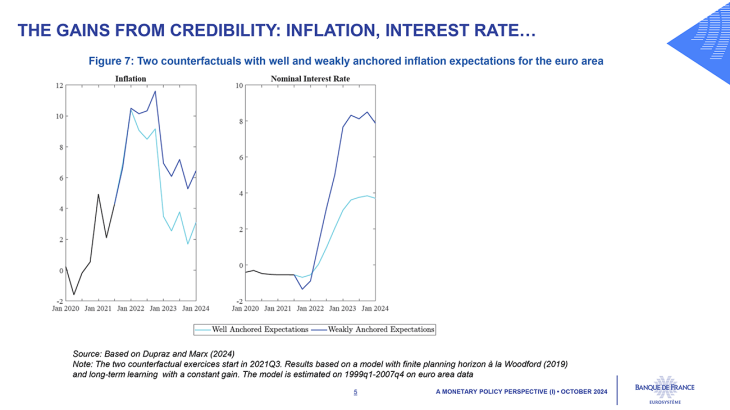

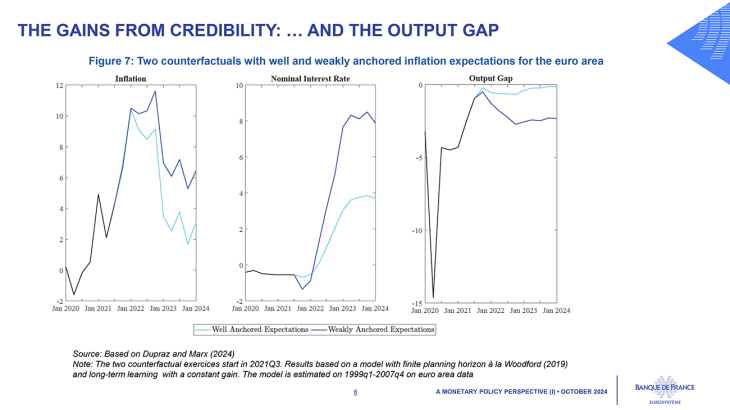

By contrast, a (more) credible central bank faces a virtuous circle of credibility. Past credibility anchors inflation expectations at the target, reducing the risk of an inflation spiral. This reduces the size of the interest rate hikes necessary to bring inflation down, and the associated costs on economic activity. Quantifying the impact of credibility is by no means easy, and surrounded with much uncertainty. But Banque de France research suggests that, had inflation expectations been as poorly anchored as they were in the 1970s in the US, our policy rates would have had to peak around 8% instead of 4%(Dupraz (S.), Marx (M.), “Anchoring Boundedly Rational Expectations”, Banque de France Working Paper Series no.936, December 2023).

Credibility also buys time. When a central bank is imperfectly credible, it must act immediately to calm any latent inflationary pressure and continually demonstrate that it aims at stabilizing inflation. But a credible central bank can react with a delay and still achieve nominal anchoring. Indeed, Davig and Leeper argue that what really matters is the average reaction to inflation in the medium run and not the immediate response, a sort of “long-run Taylor principle” (Davig (T.) and Leeper (E.M.),“Generalizing the Taylor Principle”, American Economic Review, 97(3):607-635, 2007). Still, the delay should not be too long as it may be wrongly interpreted as a signal for future inaction.

Central bank credibility like inflation is also global (Ciccarelli (M.), Mojon (B.), “Global Inflation”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 92, issue 3, 2010). Most central banks in advanced economies have credible and convergent inflation numerical targets (2%), a distinctive difference to the 1980s. This global credibility translates into less, and more transitory, imported inflation and hence inflation expectations. When a central bank acts against inflation and reinforces its credibility it exerts a positive externality worldwide.

Monetary policy and growth: A recent change in the balance of risks

Till now : A pragmatic approach to monetary policy tightening

Monetary policy tightening was necessary for price stability but also for sustainable long-term growth. However, it might in the short term have caused a recession or substantially increased unemployment. But it didn’t.

Several reasons have been put forward to explain this: transitory price shocks in the end, non-linearity of the Phillips curve (Benigno (P.), Eggertsson (G.B.), “Revisiting the Phillips and Beveridge Curves: Insights from the 2020s Inflation Surge”, Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, 2024) as studied by the latest WEO of the IMF (IMF, “The Great Tightening: Insights from the Recent Inflation Episode”, World Economic Outlook (Chapter 2), October 2024)… But returning to a recurring theme, credibility has reduced the output-inflation trade-off by anchoring medium-term inflation expectations and making communication about future policy reliable. The same Banque de France study -Dupraz (S.), Marx (M.), “Anchoring Boundedly Rational Expectations”, Banque de France Working Paper Series no.936, December 2023) suggests that without firmly anchoring of expectations that we witnessed, euro area output would have been 2% lower in 2023 due to a more restrictive stance, while inflation would have still been above 6%.

The near future : From the risk of inflation persistence to growth challenges and inflation undershooting risk

But the situation has now changed, so has the balance of risk. As you know, the ECB has no dual mandate but a primary mandate of price stability over the medium run. Yet, our price stability objective is symmetric, around the 2% target.

In principle, a dual mandate and symmetric inflation target are not always identical because there are sometimes trade-offs between output and inflation. But today, there is strong convergence: in the euro area, inflation persistence is no longer the sole and dominant risk. Instead, there is equally the opposite risk that inflation undershoots, especially if growth remains subpar. In the September ECB staff projections, inflation was expected to fall to 2.2% in 2025 and 1.9% in 2026. But market-based expectations point to inflation already below 2% in 2025; and according to the latest actual inflation data, the euro area could be at 2% inflation already early 2025.

On the real side, our real GDP forecast was revised down compared to the June round. So far, we can see the expected soft landing, but not a further take-off. Based on this dual assessment of significant downside risks on inflation as well as on growth, our Governing Council decided last week to lower the DFR by 25 basis points to 3.25%.

For the near future, I plead for agile pragmatism in the further reduction of our restrictive bias. Pragmatism, with full optionality for each of our future meetings, based on incoming data and forecasts. And agile: we are not behind the curve today, but agility should prevent us from running such a risk in the future. The risk of reducing too late our restrictive stance could indeed become more significant relatively to the one of acting too quickly. On our terminal rate, it’s obviously too early to tell. However if we are next year sustainably at 2% inflation, and with still a sluggish growth outlook in Europe, there won’t be any reasons for our monetary policy to remain restrictive, and for our rates to be above the neutral rate of interest.

When victory against inflation is in sight, monetary policy shouldn’t inflict excessive or prolonged restraint to activity and employment, and hence to our fellow citizens. This is about consistency with our secondary objectives in the EU Treaty. That said, the most significant growth challenges in Europe are beyond monetary policy. Low potential growth is structural, due to a lack of innovation, as stressed by the recent Draghi’s and Letta’s reports. Europe faces the joint challenges of the demographic, energy and digital transitions, in a more fragmented world. National governments and Europe as a whole must act urgently.

Monetary policy and its instruments: Confirming the unconventional toolbox but being ready to adjust it

Let me now turn to a rapid and personal reflection about our monetary policy toolbox, in its two main “non conventional” elements.

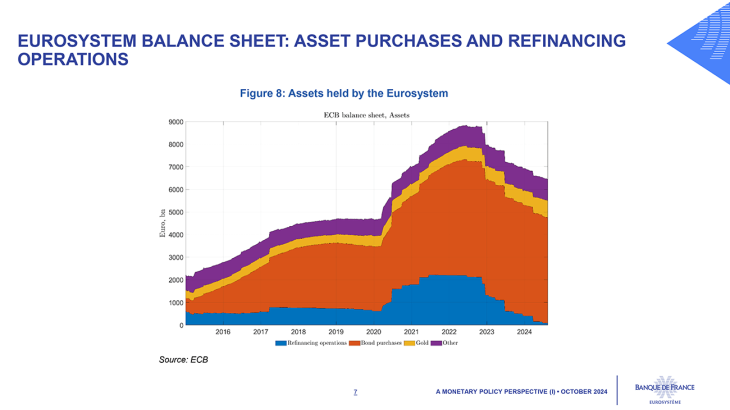

Liquidity management and balance-sheet tools

Central bank balance-sheet tools, like asset purchase programmes and LTROs (Figure 8), were designed in crisis times, either to preserve an effective monetary policy transmission when specific market segments were under strain, or to ease the monetary policy stance when required and conventional tool was unavailable due to the Effective Lower Bound.

Beyond crises times, we are for sure committed to provide adequate liquidity to financial institutions and markets, avoiding scarcity as demonstrated by the latest update of our operational framework.

That said, the 2025 strategy review of the ECB will study the adequate use and limits of each balance-sheet tool in depth, but let me share with you three key principles that, in my view, we should keep in mind.

First, taking interest-rate risk in our balance-sheet should be restricted to operations whose primary objective is to ease the stance or protect the transmission by reducing the term premium and therefore long term yields. When the primary objective is rather to inject liquidity, it should be done by lending short-term or at floating rates for LTROs. These were by the way an interesting European innovation not used in the US. But, the initial pricing of TLTRO-III at quasi-fixed rates had been a mistake, which had to be later recalibrated. For the same reason, in our new operational framework, our future structural portfolio of assets to keep money market rates close to the deposit facility rate could contain a significant proportion of short duration bonds.

Second, both in our QE or structural portfolio holdings, we should prioritize government bonds and supranationals to limit our direct exposure to the nonfinancial corporate sector in our balance-sheet. That being said, such programmes are not and should never be designed to fund governments nor to help fiscal stimulus – a widespread illusion.

Third and finally, one important lesson from the recent years is that we should not condition one instrument on another. Doing so creates communication issues if one programme has to be stopped rapidly. For instance, using asset purchases to make forward guidance more credible can happen to be unwise, as we could see early 2022 when we had to stop gradually asset purchases before being able to raise rates.

Forward guidance and communication

Communicating about future policy reinforces the expectations channel of monetary policy. It is sometimes viewed as binary, while, in practice, communication belongs to a continuum from full commitment to total silence.

On one extreme of the spectrum, forward guidance works, in principle, through the commitment to depart from the standard policy. However, central bankers should not be unconditionally pre-committed to any interest rate path but keep optionality, at least, beyond few quarters. At shorter horizons, date-contingent forward guidance might still be valid (Villeroy de Galhau (F.), Monetary policy in uncertain times, speech, 15 February 2022) . For signaling policy at longer horizons, if needed, state-dependent (and hence more humble) forward guidance would be more appropriate, as it combines optionality and effectiveness.

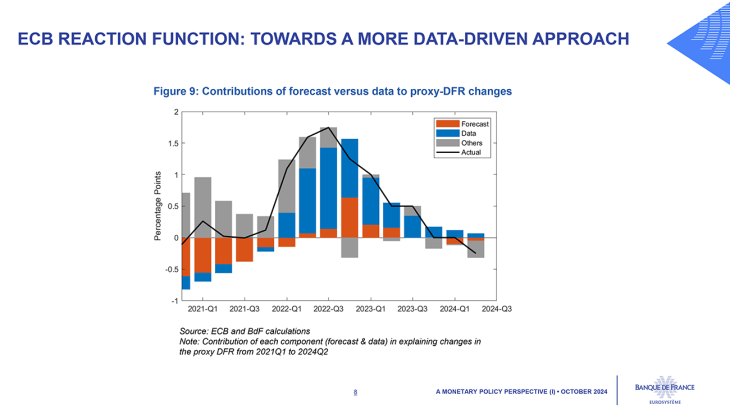

At the other side of the spectrum, the central bank can give no indications whatsoever. With the recent inflation surge, the ECB shifted to a meeting-by-meeting and data-driven approach, an evolution warranted by high uncertainty and inflation forecast instability. Recent BdF work finds that during the inflation surge the ECB reaction function became less “inflation forecast-based” and more “underlying inflation data-driven’”.

But now that we are back to a “normal” inflation regime, our reaction function should become more “forward-looking”, with greater confidence on forecasts, and rely less on monthly flash data.

Between these two sides of the spectrum, there is soft signaling, whereby the central bank makes clearer its reaction function. Contrary to forward guidance, it is not a commitment to deviate from the standard reaction but it can still influence market expectations of future policy. Such soft signaling is our everyday life business, while the two other forms (no signaling and forward guidance) should be the exceptions.

So what did we learn in the end?

First, a recession is not needed to disinflate the economy when central banks are credible and therefore the expectations channel is strong. Central bank credibility also buys times in case of uncertainty which was helpful at the end of 2021. However, credibility is not magic but must be sustained through action. Central banks cannot completely promise “immaculate disinflation”, but the adjustment to shocks is then smoother.

Second, monetary policy must remain agile and pragmatic in the face of changing balance of risks. We have to be prepared to face any new situation by relying more than ever on our symmetric medium-term 2% inflation target. This is all the more necessary that we are facing an increasingly volatile and uncertain geopolitical environment as well as the demographic, climate and digital transitions.

Third, the recent inflation surge implicitly taught us a lot about the ex post cost-benefits of unconventional tools that were put in place before and during the Covid. They proved their worth and should remain part of the toolkit but all could be adjusted to be more flexible and less costly. These are only few preliminary thoughts where the ongoing ECB strategy review will dig further.

Central banks and monetary policy have lived their way in the last 10 years through an unprecedented sequence of lowflation, then almost deflation (during Covid), high inflation, and successful disinflation. It’s no reason for complacency, but some reasons for confidence, and for further improvement to face the challenges of the years to come.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 30th of October 2024