Do national economies move together in a globalized world? And how much of that co-movement is truly global, rather than driven by regional or dominant-country dynamics? These questions are central to debates about macroeconomic interdependence and policy autonomy.

Over the past two decades, research has suggested that world cycles — common movements in macroeconomic and financial variables across countries — are increasingly influential. According to this view, globalization has led to tighter synchronization of GDP, credit, inflation, and asset prices, particularly since the 1980s. This has reinforced the notion that open economies face limited control over domestic conditions.

In this paper, we revisit these narratives using a new, large-scale quarterly dataset covering output, prices, credit, interest rates, and stock prices for a broad set of advanced and emerging economies from 1950 to 2019.

To build it, we exploit archival publications of the IMF’s International Financial Statistics, recovering historical series that had never been made available in digital form. The result is an extensive macro-financial dataset — global in scope, with quarterly observations, and spanning nearly 70 years.

Our data allow for a more systematic analysis of global co-movements over time, and help distinguish between cycles that are truly global and those that reflect narrow geographical areas or more recent patterns. Using standard dynamic factor models, we estimate world cycles for our dataset’s variables, and assess their explanatory power across countries and time. Our results challenge key elements of the conventional view.

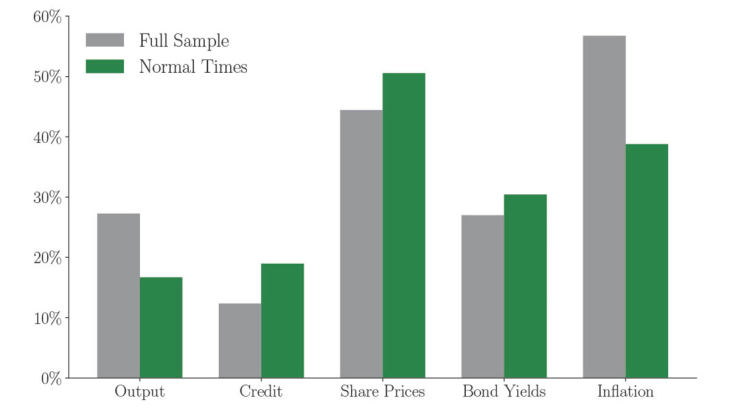

First, global factors matter more for prices (especially asset prices and inflation) than for quantities (GDP and credit). Second, while asset price synchronization increased steadily from the 1950s to the early 2000s — from around 40% to over 60% of variance explained — output and credit synchronization did not follow the same path. They were already substantial under Bretton Woods (1950–1971) and did not rise with globalization. In fact, output and credit synchronization declined after the Global Financial Crisis, and the global component currently explains less than 20% of GDP variation in normal times. Third, we show that trade and financial integration have different effects: while trade openness tends to raise output synchronization, greater financial openness is associated with stronger co-movement of asset prices but weaker co-movement of output.

To explain this disconnect, we propose a simple model where countries choose both their asset portfolios and production technologies. Financial integration expands risk-sharing opportunities, which raises cross-border asset price correlations. But it also encourages countries to adopt riskier, higher-return technologies, increasing idiosyncratic output volatility and reducing output synchronization. In other words, more synchronized markets can coexist with more desynchronized real economies — a pattern consistent with the data.

These findings have several policy implications. First, world cycles do not require deep financial integration: significant global co-movements existed under Bretton Woods despite strict capital controls. Second, the modest role of global factors in driving GDP and credit suggests that countries may retain more policy autonomy than often assumed — especially outside crisis episodes. Third, the divergence between synchronized prices and desynchronized quantities complicates the task of central banks, whose policy instruments often target both.

Keywords: World Cycles, Business Cycles, Financial Cycles, Financial Integration, Trade Integration, Globalization.

Codes JEL : E32; F41; F42