Nature provides economic activities with services whose economic value is often not reflected but which are nevertheless essential for production and, by extension, for price stability. Although ongoing environmental degradation threatens the continuity of these services and the economic activities that depend on them, these risks remain insufficiently understood and are rarely quantified in macroeconomic terms. This study examines how nature degradation and policies aimed at halting it can have tangible effects on the economy as a whole, using the agricultural sector as an illustration.

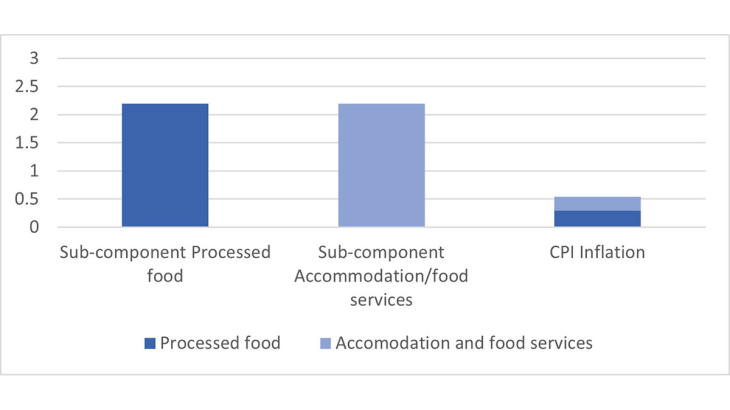

First, we design a case study of physical risks for the agricultural sector to show that disruptions to essential ecosystem services – such as pollination, pest control, invasive alien species and water regulation – can drive up food prices and ultimately affect headline inflation. Using a global value chain model, we simulate the consequences of natural hazards for agricultural productivity in a group of countries, as well as the impact on agriculture’s relative prices for these countries, and in particular for France. Our results show that a shock affecting major crops could raise the relative prices of agriculture by 13% in France. We then use this temporary shock as an input in an inflation forecast model to assess the effects: we find that such physical risks could increase food price inflation in France by more than 2 percentage points and add around 0.5 percentage point to headline inflation, with most of the impact materializing over a one- to two-year horizon. Although these shocks are modelled as one-off events, repeated or intensified nature-related shocks could generate more persistent inflationary pressures.

In a second exercise, we model the impact of measures aimed at limiting pollution and reducing pressure on biodiversity. These policies are essential, but if they are implemented in a disorderly and unplanned manner, they can reduce agricultural production and lead to sharp price increases. In France, for example, disorderly implementation of strong restrictions on the use of pesticides and fertilisers could reduce GDP by around 0.2% and increase crop prices by 12% over the medium to long term. Similar effects are observed in other European countries, with particularly significant impacts in areas of intensive agriculture. These results should not be considered as ex-ante policy evaluation but as an illustration of the cost of insufficient anticipation of these policies. Besides, our results do not reflect the potential economic or health benefits associated with the transition of the European agricultural system.

Together, these two illustrative exercises demonstrate that while nature degradation can increase inflation, a well-planned and coordinated transition would mitigate these effects more effectively than disorderly action or inaction. This highlights that nature degradation is not just an environmental issue: it can lead to higher costs for households and businesses, and may pose challenges for monetary policy, particularly if such shocks become more frequent and persistent, with potential spillovers to other sectors and/or risks of de-anchoring inflation expectations. Our study also highlights gaps in existing modelling frameworks. Standard macroeconomic models often struggle to capture the complex interactions between nature and the economy, such as feedback loops, sectoral interdependencies, and non-linear effects that can amplify initial shocks. Better data, improved models, and further research are needed to systematically integrate nature into macro-financial risk assessments. Central banks have an important role to play in enhancing the representation of these risks and integrating them into policymaking.

Keywords: Nature-Related Risks, Macroeconomic Modelling, Price Stability

Codes JEL : Q57, E31, E37, C60, E50, Q18