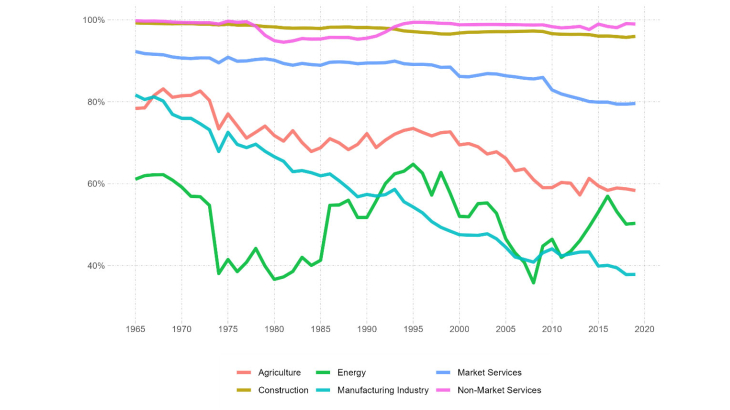

In this paper, we calculate 'made in' indicators using multi-regional input-output tables. The 'made in' of a country represents the share of domestic value added in the country's final demand. The 'made in France' indicator declined between 1965 and 2019, falling from 89% to 78%. In 2019, it is high in construction (96%) and market services (80%), but much lower in manufactured goods (38%) compared to 82% in 1965. In services, domestic demand is associated with domestic production, particularly in sectors such as food services, health, and education. Moreover, intermediate consumption in services largely corresponds to domestic production. In contrast, industrial and agricultural goods, as well as their intermediate consumption, are often imported.

The 'made in' indicator has similarly declined in other major European countries such as Germany, Spain, and Italy. In 2019, these countries exhibited similar 'made in', while less populated countries like Ireland and the Netherlands, which are more integrated into international trade, had lower rates. This downward trend reflects the expansion of global value chains and the increasing integration of China into global trade. Since the 2000s, 'made in China' has been replacing 'made in Europe' in French consumption. The share of 'made in China' in manufactured goods consumed in France increased, while the share of ‘made in France’ in domestically consumed stood at only 38% in 2019, having significantly declined since 1965. Furthermore, around 30% of French exports in 2019 consisted of imported products, compared to 15% in 1965, highlighting the increasing participation in global value chains.

The effect of diversification on economic volatility is ambiguous and contingent on the underlying sources of shocks. When shocks are primarily country-specific (domestic policy uncertainty, etc.) trade integration can serve as a buffer. By enabling firms to diversify across multiple countries and supply chains, trade reduces reliance on any single national economy. In this paper, by contrast, we focus on sectoral shocks, such as geopolitical, climate related, or supply chain disruptions and we measure trade vulnerabilities of French economy at this level. A product consumed in France can be particularly vulnerable to these risks when it has 1) a high import content, 2) a high concentration in a few sectors and countries, and 3) a French import structure similar to that of other countries, indicating a concentrated global supply that constraints import diversification. The sectors where vulnerabilities, measured according to these criteria, are most pronounced are pharmaceuticals, textiles, refining, other transport equipment, and IT.

We also propose an accounting exercise illustrating the spillover effects of setting up a new plant in France rather than abroad, linked to the interconnections of value chains as measured in multi-regional input-output tables. The initial plant's purchases of inputs generate additional production for these suppliers, which in turn uses intermediate consumption, and so on. The supply chain, both domestic and global, faces additional demand and therefore increases production accordingly. Consequently, economic activity, employment, and CO2 emissions varies in each country. These effects are simulated here by substituting part of the imports of goods with domestic production, while keeping total demand unchanged. In this exercise, if a manufacturing plant producing € 1 billion of value added were reshored in France rather than abroad, the value added in France would increase by € 2.0 billion, with a spillover effect on the supply chains of this new plant amounting to € 1.0 billion. This would create 24,400 jobs in France, 10,500 directly and 13,900 indirectly. While this exercise provides estimates of employment creation, it does not make an explicit assumption about whether these jobs are filled by previously unemployed individuals or those moving from other firms. The methodology relies on the existing average employment intensity of the sector. Furthermore, the model does not account for potential resource constraints, including in the labour market that could affect the actual employment creation.

Keywords: Multi-Regional Input-Output Model, Reshoring, Carbon Footprint

Codes JEL : C67, F62, Q53