Households' financial vulnerability can help to explain the unusual magnitude of the economic downturn observed during the Great Recession. When agents' debt burden is high, shocks having a direct impact on financial conditions are expected to have a larger impact with respect to the case where the debt burden is low (Kiyotaki 1997).

In this paper we ask how financial vulnerability affects the propagation of housing and credit shocks.

To answer this question, we estimate an econometric model on US data, in which the impact of shock depends on the level of financial vulnerability. To track financial vulnerability, we use the Debt Service Ratio (thereafter DSR), i.e. the fraction of income that households use to pay back their debt (pay interest and amortize the principal), in three-year difference. Our model includes real, financial and monetary variables and, through sign restriction method, we jointly identify a wide set of structural shocks: financial shocks (housing, credit shocks), monetary shocks and real shocks (aggregate demand, aggregate supply, investment shocks).

The choice of DSR features different positive aspects. First, the DSR is a measure of financial fragility that takes into account three different components of financial vulnerability: i) the cost of debt, related to the effective interest rate payed by the average household; ii) the aggregate stock of debt issued by households, iii) the evolution of households' income.

Second, the DSR ex-ante informs about the build-up of financial risks in households' sector, as opposed to variables which signal only current financial distress (e.g. financial stress indicators) or ex-post signalling indicators (e.g. NBER recessionary periods, industrial production evolution). In this respect, the transformation in DSR is widely used in risk analysis to detect the build-up of financial risk in the economy given its good signalling properties as an early warning indicator of financial crisis.

The key message of this paper is that the propagation of financial shocks under financial vulnerability depends on the origin of the shock itself.

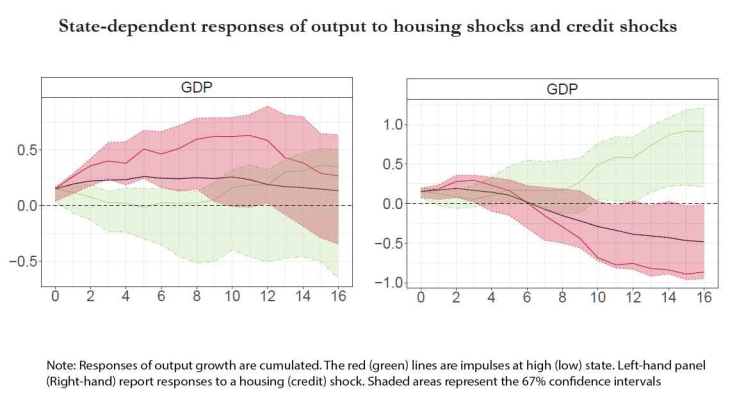

First, financial vulnerability amplifies the impact of housing shocks and make them more persistent. Under high vulnerability the effect on output to a housing shock is overall twice as large as the effect obtained in a linear model featuring the same specification. Instead, under low vulnerability, the response to an housing shock of a similar size is not statistically significant. The amplification under financial vulnerability can be read in light of the theoretical works that study the presence of financial accelerators in the economy (Kiyotaki 1997). In these models, agents are subject to borrowing constraints and can borrow only up to fraction of their collateral. If their collateral decreases because of an incoming shock, so does the debt limit: agents will be forced to reduce their leverage and spend less, amplifying the initial fluctuation. This type of channel seems to be stronger after a large increase in the DSR. A possible interpretation could be that the DSR provides information on the probability of default of households, whereas collateral value determines the Loss Given Default of their loan. When DSR is high, agents feature a larger probability of default, making lenders more sensitive to the evolution of collateral value (i.e. Loss Given Default).

Second, the positive effect of credit shocks are overturned under high vulnerability: expansionary credit shocks have negative effect on the medium term. The overshooting of credit shocks under high vulnerability is consistent with the presence of debt overhang, which induces financially vulnerable agents to deleverage after a period of debt expansion.

In an extension of our baseline model we find that under high vulnerability recessionary housing and credit shocks have a more persistent effet on output than expansionary shocks.

In another extension, we further disentangle credit demand shocks from credit supply shocks. This identification allows to establish that financial vulnerability makes them less persistent or even negative on the medium run, in line with the interpretation that such expansions are hampered by possible debt overhang. However, this amplification is substantially stronger for credit supply shocks.

Those results call for the monitoring of households financial vulnerability to correctly assess the potential amplification effects of incoming financial shocks. Moreover, they highlight the potential beneficial effects of macroprudential policies in limiting the excessive build-up of financial vulnerability, and consequently reducing the sensitivity of the economy to financial shocks.