As inflation reached levels unseen in recent decades in most advanced economies, a primary concern was the extent to which this rise in inflation might become ingrained in inflation expectations, especially those of firms due to their role in setting prices. But because there are few surveys of firms’ inflation expectations, it has been difficult to assess how firms’ inflation expectations changed during this period, as well as whether those inflation expectations affected their willingness to raise workers’ wages. In this paper, we use a survey of firms in France conducted between 2020 and 2024 to study these questions.

This survey has four unique characteristics that are not commonly available in other surveys of firms. First, it covers the full inflation cycle starting in 2020 when inflation was close to 0 and finishing at the end of the disinflation process in 2024, which allows us to gauge how the inflation cycle affected the anchoring of inflation expectations. Second, the survey includes questions about inflation at different horizons, so it can speak to the persistence of the inflation process, as perceived by firms, and whether it changed along the inflation cycle. Third, it includes questions on firms’ expectations about the growth of wages in their firm over the next year, thereby providing an unusual link between aggregate inflation expectations and firm-level wage expectations. Finally, the survey also includes questions about the planned decisions of firms, such as their expected and past price changes and employment growth, so that expectations can be related to their decisions.

With this unique data, we examine how inflation expectations reacted to the inflation surge and then to the disinflation process. First, as inflation rose sharply in France in 2022, firms were initially surprised by the extent of the increase, with both their perceptions and expectations significantly under-responding (Figure 1). However, by 2023, both the inflation expectations and perceptions of firms had significantly overshot actual inflation dynamics.

Second, we find that the average perception but also short- and long-term expectations of inflation all came back to the target at the end of 2024. Thus, while all expectations deviated significantly from the inflation target during the surge, this deviation was relatively short-lived. Furthermore, disagreement among firms about future inflation rose sharply during this period, consistent with what has been observed for households, but the dispersion of expectations also decreased sharply during the disinflation process.

Third, as the inflation rate surged, the term structure of firms’ inflation expectations pointed to a decline in the perceived persistence of inflation, but this decline was short-lived. In other words, firms initially expected the rise in inflation to be more transitory than what they usually expected for inflation changes, but their expectations ultimately went back to assuming the same persistence as usual. One possible explanation for the decline in persistence could be that the inflation surge was initially tied to a sharp increase in energy prices, which might have been expected to have only a transitory effect on inflation dynamics. Regardless of the source, firms initially perceived the inflation spike as driven by a different process than during the low inflation period. Overall, and in contrast to the experience of other countries like the U.S. (e.g. Coibion and Gorodnichenko 2025), we do not find a significant persistent de-anchoring of inflation expectations following the inflation surge.

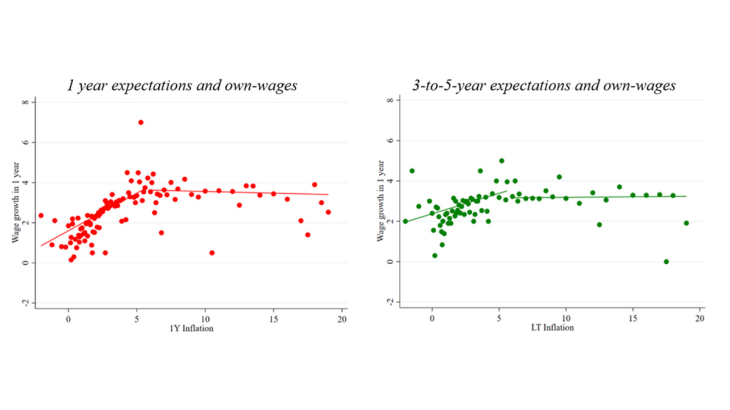

The survey also allows us to assess how much inflation expectations matter for firms’ decisions. First, we find that firms’ wage expectations are closely tied to their expectations of year-ahead inflation and their beliefs about recent inflation, but we consistently observe almost no relationship between long-run inflation expectations and firms’ wage expectations (Figure 1). Instead, it appears that firms expect their year-ahead wage adjustments to primarily reflect recent price dynamics as well as those anticipated over the near future. We also document heterogeneity in the pass-through between inflation and wage expectations across firms. The pass-through is generally stronger for firms that are more attentive to inflation. When inflation is higher than 3 to 4%, the relationship between expectations and wage growth is weakened. This lower pass-through during the high inflation period primarily comes from the subset of firms that expected a very high inflation rate (“inflation disaster”): these firms did not expect to adjust their wage expectations to the inflation surge (Figure 1), and they were more numerous during the high inflation period.

Finally, we consider the degree to which expectations pass through into decisions and the extent to which (and whether) that changed during the high-inflation period. We document evidence consistent with a pronounced decline in the pass-through of expectations into decisions. While we can identify a strong passthrough from these expectations into firms’ ex-post prices and employment during normal times, this passthrough significantly weakened during the high-inflation period. This suggests that, even as wage and inflation expectations rose sharply during the inflation surge, their likely effect on prices and employment diminished, muting their importance during this particular episode. This changing pass-through is again primarily explained by the subset of firms expecting very high inflation (i.e. an “inflation disaster”). Among firms who were not anticipating this type of inflation disaster, we observe little change in the pass-through across high or low inflation environments.

Keywords: Expectations, Inflation, Rational Inattention, Surveys, Firms

Codes JEL : E2, E3, E4