The Flattening of the Phillips Curve and the Disappearance of Routine Jobs

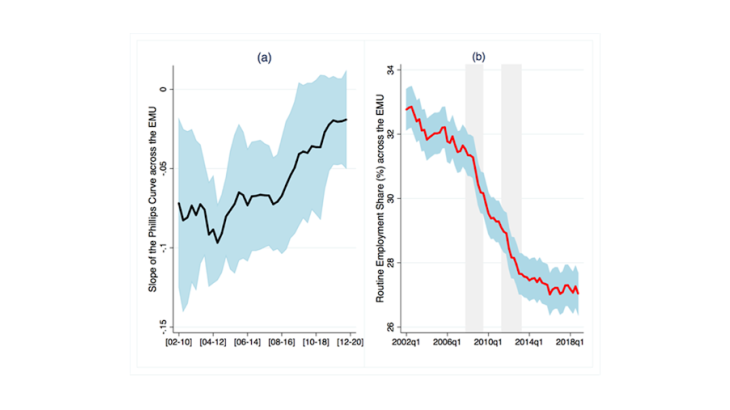

There has been an ongoing debate since the 1970s on whether or not the price Phillips curve (PC) –the negative relationship between inflation and unemployment– is still alive or is dead (e.g. Berson et al. 2018 show that it still exists). The answer often depends on the methodology, the sample of countries considered and the econometric specification used. We argue that in the EMU the price PC is still alive but has weakened in recent years (Chart 1.a). The literature has put forward two explanations for why this might have happened. The first relates to the anchoring of inflation expectations and the stronger commitment of central banks to keep inflation low (see Blanchard (2016)). The second is associated with structural changes in economic fundamentals due, for example, to digitalisation, population ageing, globalisation, and labour market dynamics. This blog, based on Siena and Zago (2021), focuses on the latter and shows that transformations in the occupational composition of the labour market matter for the flattening of the price PC.

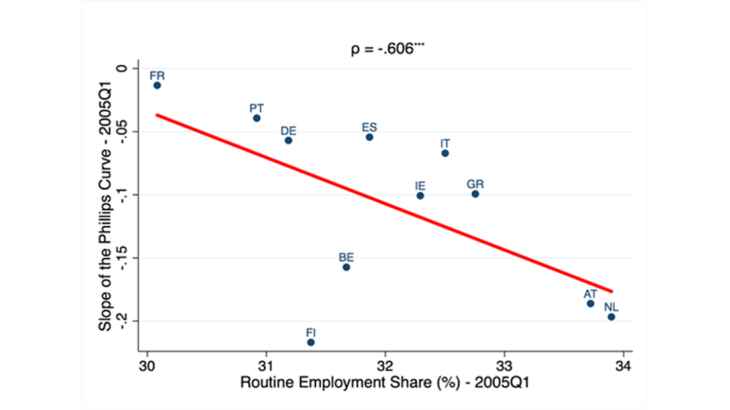

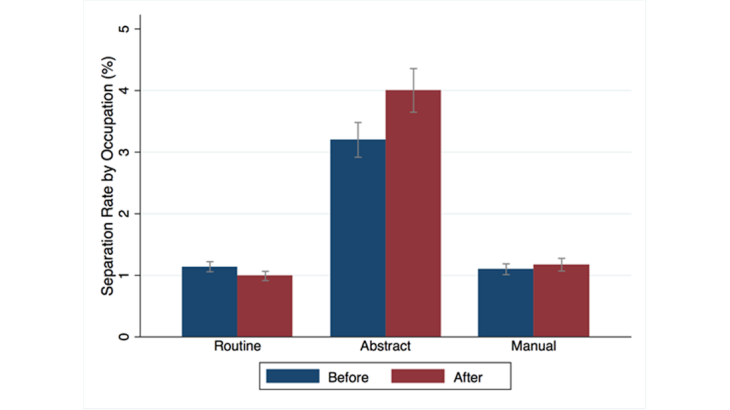

In the last twenty years, the EMU labour market has changed, including its occupational composition. As shown in Chart 1.b, the share of routine jobs has declined consistently, and this phenomenon temporarily accelerated during the Great Recession (GR) and the Sovereign Debt Crisis (SDC) – grey shadowed areas. This phenomenon is known as job polarisation and describes the long-run decline of the share of clerical and production occupation (routine jobs) in favour of managerial, professional, service and sales jobs (abstract jobs). As explained in Acemoglu and Autor (2011), this long-run trend is mostly due to automation, i.e. the progressive substitution of routine workers with highly-performing machines and technologies. But it is not only about long-run dynamics. Polarisation also follows the cycle: routine jobs are destroyed faster during downturns (see Jaimovich and Siu (2020)). In this regard, we exploit these properties of job polarisation to show that employment composition matters for the flattening of the PC. First, we show that, at any point in time, countries whose share of routine jobs is relatively high exhibit a stronger relationship between inflation and unemployment. Conversely, when a country’s share of routine employment is relatively low, the slope of the PC is flatter (see Chart 2). Second, over time, this relationship evolves with the change in job polarisation.