What are the benefits of conducting monetary policy under an inflation targeting regime? In theory, higher commitment for policymakers due to the presence and communication of an explicit numerical inflation target makes monetary policy more effective. However, finding benefits of adopting an inflation targeting regime in the data is a complicated task. One reason is that inflation targeting became popular after 1990, which was a period of low macroeconomic volatility across many advanced economies that became known as the Great Moderation. The ‘good luck’ due to the absence of larger shocks makes it harder to detect ‘good policies’ when it comes to average outcomes like the reduction in inflation rates (Ball and Sheridan 2003).

We use large natural disaster shocks and show that economic outcomes differ across countries in the immediate aftermath of such shocks depending on whether or not they have an inflation targeting regime (Fratzscher, Grosse Steffen and Rieth 2017). The approach considers the unpredictability of natural disasters in conjunction with their significant economic consequences in order to isolate the effects of inflation targeting in deep recessions.

Results based on a sample of 76 countries over the period 1970-2015 suggest that there are significant gains from adopting an inflation target in terms of macroeconomic stabilisation. During the four years after a natural disaster with reported insurance claims of 1% of GDP, output growth is on average 0.16 percentage point higher and inflation rates 0.44 percentage point lower per quarter in inflation targeting countries. Although our focus is not on the Great Recession of 2009, these findings support the view that inflation targeting might have helped to cushion the adverse effects of the Great Recession (Miles, Panizza and Reis 2017).

A different monetary-fiscal policy mix lifts output growth and lowers inflation

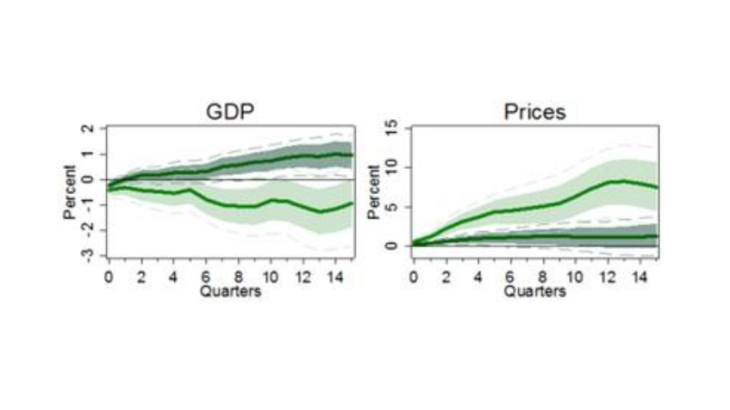

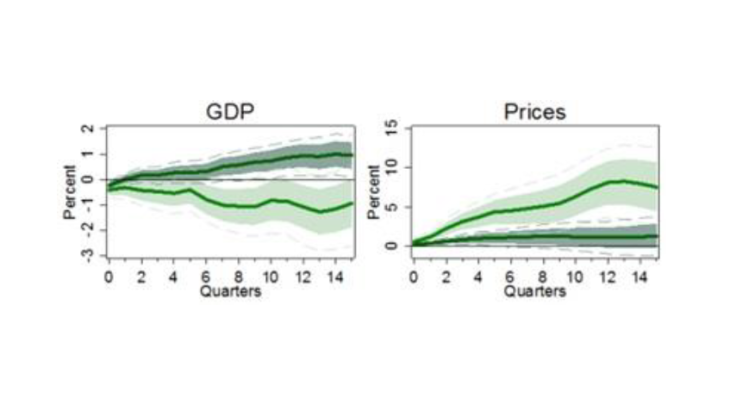

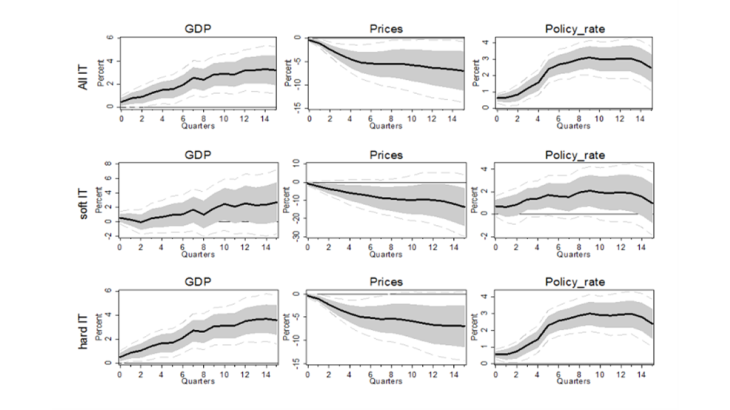

A natural disaster initially leads to a contraction in output and higher inflation in both inflation targeting and non-targeting countries. However, in inflation targeting countries, the recovery is faster and more pronounced (see Figure 1). This is due to a recovery in private consumption and, to a lesser extent, investment activity (see Figure 2). In line with a higher inflation rate, targeters respond with some lag to the shock by gradually tightening monetary policy during the recovery period.

In contrast, non-targeting countries lower the policy rate immediately, which translates into higher inflation rates with some lag, albeit not resulting in output growth. One reason is that the response of government spending is more pro-cyclical in non-targeting countries, weighing on GDP growth. We interpret this result in light of complementarities between monetary and fiscal policy. The presence of inflation targeting enforces fiscal discipline in normal times, thereby fostering more counter-cyclical government spending in the wake of large disasters.