Post No.406. While state aid has emerged as a key instrument for countering the effects of recent shocks, its increased use in Europe raises concerns about distortions and a race for subsidies between Member States. Faced with the need for investment in the ecological transition and for strategic autonomy, the EU must now strike a new balance and coordinate this state aid more effectively.

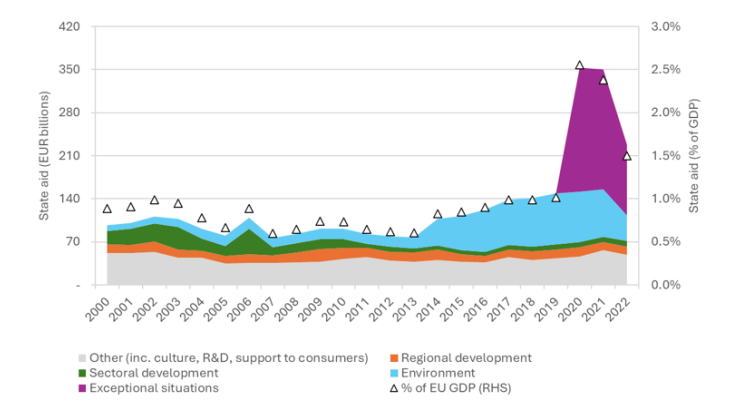

Chart 1 – State aid in the EU by objective (in EUR billions at constant 2022 prices (left) and as a percentage of EU GDP (right): 2000-22

Note: In 2022, state aid totalled EUR 228 billion (in constant 2022 euros) and represented 1.5% of EU GDP.

The boom in state aid within the EU has been facilitated by the loosening of rules in the wake of the crisis.

While state aid is granted at Member State level, it is strictly regulated by the EU. It is prohibited in principle (Article 107 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union) because it is deemed incompatible with the internal market insofar as it may affect competition or trade between Member States. However, certain derogations permit Member States to use it. State aid is used to steer the economy by supporting certain sectors (such as agriculture, regional and sectoral development, the environment or R&D) using grants, loans, guarantees or tax incentives that benefit a country's economic players (Chart 1). Although the European Commission is tasked with ensuring that Member States comply with the principles governing the use of such measures, there has been an unprecedented boom in state aid in recent years. After peaking at 2.6% of EU GDP in 2020 (Chart 1), state aid accounted for 1.5% in 2022, compared with only 0.8% over the 2000-07 period (European Commission).

This increase has been driven by the gradual relaxation of state aid rules, especially to counter the economic effects of Covid-19 and geopolitical crises (US-China trade war and Russia's invasion of Ukraine). These crises have highlighted the need for the EU to reduce its numerous dependencies (trade, energy, technology) and bolster its strategic autonomy. A temporary framework limited to the financial sector was introduced in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. More recently, in 2020, the Covid-19 crisis led to specific measures (the State Aid Temporary Framework) for sectors including tourism and transport, while a new dedicated framework (the Temporary Crisis Framework) was introduced in 2022 to address the economic impact of the war in Ukraine on the energy and agriculture sectors.

State aid has become a key component of the green industrial policy that the EU is trying to deploy in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 while boosting its strategic autonomy (Veugelers et al., 2024). The most recent easing measures were introduced in 2023 in response to the US Inflation Reduction Act (the Temporary Crisis Transition Framework). The objective is to support certain highly exposed sectors, facilitate the financing of renewable energies, and respond to the widespread use of industrial policy for economic security purposes (Juhàsz et al., 2023) in most advanced economies, as exemplified by the US initiatives launched as of 2021 (the Jobs Act (2021) and CHIPS Act (2022)). For example, in July 2024, the Commission approved a state aid scheme for France, for a potential amount of EUR 10.82 billion over 20 years, to support the development of offshore wind energy.

The race for subsidies: the risk of distorting the single market

There is no consensus among Member States on relaxing the rules for providing state aid, and some fear that this could risk distorting the market. Despite the “targeted” and “temporary” nature of the aid granted and the European Commission's desire to maintain a balance between state aid and the single market, concerns remain. Criticism from certain countries focuses mainly on the perceived unfairness of the use of aid between Member States and the risk of distorting competition. These Member States (most notably Sweden, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ireland and Poland) contend that state aid mainly benefits the largest, least indebted countries, which is contrary to its purported exceptional purpose. From this perspective, the granting of state aid could actually exacerbate regional disparities within the EU and, in the long term, contribute to the fragmentation of the single market (IMF, 2023).

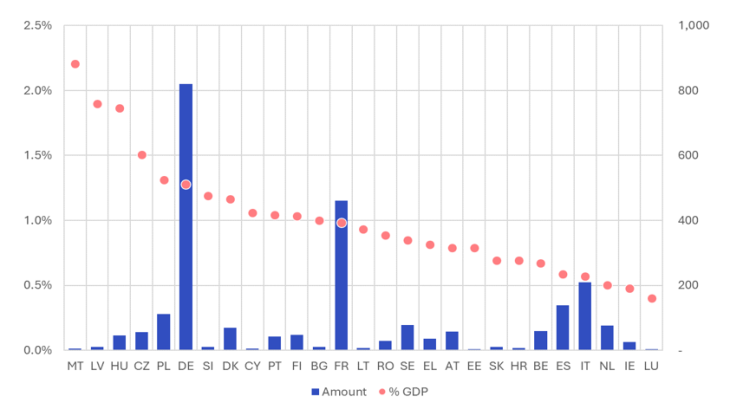

However, as we will demonstrate below, the risk of distorting the single market through the use of EU state aid needs in some respects to be put into perspective. First, there is actually considerable disparity in the use of state aid by Member States in relation to their economic clout within the EU. Admittedly, in terms of amount, Germany, France and Italy are the top three countries, accounting for 34%, 19% and 9%, respectively of total state aid actually spent in the EU between 2000 and 2022 (i.e. a cumulative total of nearly EUR 820 billion, EUR 460 billion and EUR 210 billion, respectively, for these three countries at 2022 prices). However, when expenditure is measured as a percentage of GDP, Germany, France and Italy rank only 6th, 13th and 24th among Member States (Chart 2).

Chart 2 – State aid by amount (EUR billions) and by % of GDP (2000-22)

Note: Over the period 2000-22, state aid spent by Germany (DE) amounted to EUR 820 billion, representing 1.28% of its GDP.

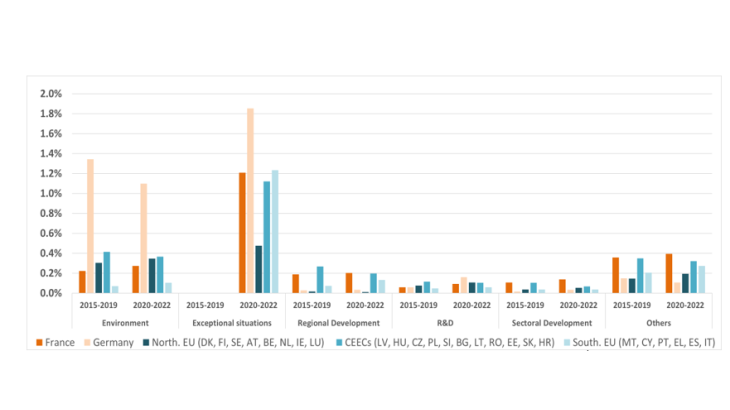

Moreover, this contrasting picture can be explained in particular by different funding priorities between Member States. Excluding exceptional crisis-related expenditure, state aid in support of the environment has become predominant, especially since 2014 in most Member States (Chart 1), with the exception of southern European countries (Chart 3). Furthermore, as a share of GDP, state aid expenditure on the environment remained relatively stable after 2020 in all Member States.

In addition, among the EU’s most recent members, state aid is used especially for regional and sectoral development and for R&D. Between 2020 and 2022 for example, state aid expenditure in Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs) as a share of GDP reached 0.20% for regional development, well above the levels in northern and southern countries (0.01% and 0.13% of GDP, respectively). As such, state aid continues to be a lever for strengthening economic convergence among EU countries, in line with its original purpose.

Chart 3 – Comparison of the proportion of state aid in GDP (%) of Member States by sector before/after the Covid-19 crisis (i.e 2015-19 and 2020-22)

Note: Between 2020 and 2022, average annual state aid to support the environment as a percentage of GDP was 1.10% for Germany and 0.10% for southern European countries.

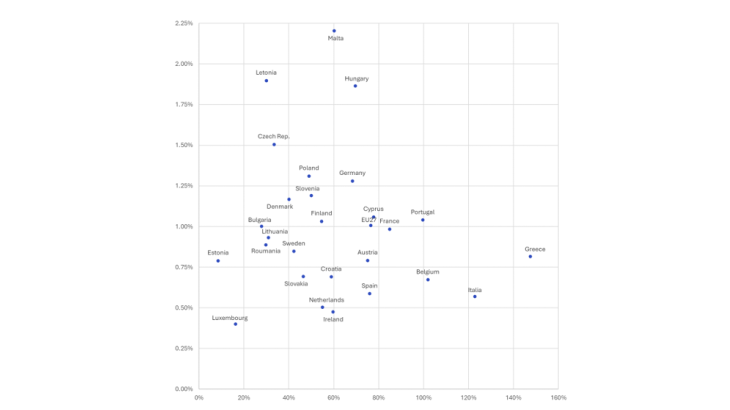

Lastly, the use of state aid does not appear to be correlated with Member States' fiscal leeway, as approximated by their debt-to-GDP ratio (Chart 4).

Chart 4 – State aid/GDP (%) and public debt/GDP (%) (2000-22)

Note: State aid accounts for 2.2% of Malta's GDP and its public debt stands at 60% of GDP

Towards a Europeanisation of state aid in the name of strategic autonomy?

The European Commission estimates that an additional EUR 622 billion a year will be needed to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. The EU must therefore increase coordination between national strategies if it wants to reconcile the transition objective with preserving the internal market and macroeconomic balances between Member States.

One of the risks of a race for subsidies between Member States to attract major industrial projects is a potential decrease in the efficiency of public spending. In this regard, the Letta report (2024) recommends, for example, ending temporary measures at national level in favour of a more European approach to state aid, with the creation of a mechanism for contributing to state aid financed by Member States and dedicated to pan-European projects.

Similarly, in light of the risks of uncontrolled growth in state aid, Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) appear to be a particularly useful tool. IPCEIs aim to facilitate public investment in certain sectors or technologies of strategic benefit for the EU (batteries, hydrogen or semiconductors, for example) and must involve at least four Member States. These projects may represent a compromise solution between industrial policy and competition policy. They strengthen industrial policies while protecting the single market from the risk of fragmentation. However, these programmes continue to be underused: since 2010, only EUR 3.9 billion in state aid has been mobilised in the EU to support IPCEIs, representing only 0.2% of total state aid mobilised over the period. Among the 12 Member States that have used state aid in support of IPCEIs, France, Finland and Denmark are the countries that have invested the most in these types of project as a proportion of their GDP. The Draghi report (2024) made strengthening IPCEIs a key objective for enhancing coordination and cooperation between Member States.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 21st of October 2025