- Home

- Governor's speeches

- “Can our tax debate be rational?”

“Can our tax debate be rational?”

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 27th of November 2025

Symposium marking the 20th anniversary of the CPO – Paris, 27 November 2025

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure for me to open today's symposium dedicated to the 20th anniversary of the Conseil des prélèvements obligatoires (CPO) in our Jacques Delors amphitheater. I would like to pay tribute to the CPO, which since its creation in 2005 has embodied values that are precious – and increasingly rare – in the public debate: objectivity, expertise and independence. The Banque de France fully identifies with these values. I am familiar with the CPO's requirements, having produced a report for its predecessor, the Tax Council, in the 1980s, and then having served as Director General for Taxes.

Allow me to begin with a semantic observation: in English, the word “fiscal” [which appears in the French title of this symposium: « Notre débat fiscal peut-il être rationnel ? »] means “budgetary”, including spending; in France, it refers solely to taxes. This may be a sign of a distinctly French passion for taxation, even more so than among our neighbours. That said, can our tax debate be rational rather than passionate? Your twenty years of experience invite us to take a long-term view of taxes and social security contributions in France, with two perspectives — historical (1) and spatial (2) — and a praise of tax wisdom (3). I will then conclude with a few remarks on our current budget debate (4).

1. A historical perspective: a question of asymmetry

Since the CPO was created in 2005, the rate of taxes and social security contributions has risen from 42.7% of gross domestic product (GDP) to 42.8% in 2024. This apparent stability masks a certain volatility, with a significant increase from 2011 onwards and a peak of 45.3% in 2017. Two-thirds of French citizens consider this level to be too high, while less than one in three (30%) say they are satisfied with the quality of public services in relation to the amount of taxes they pay to finance them.i

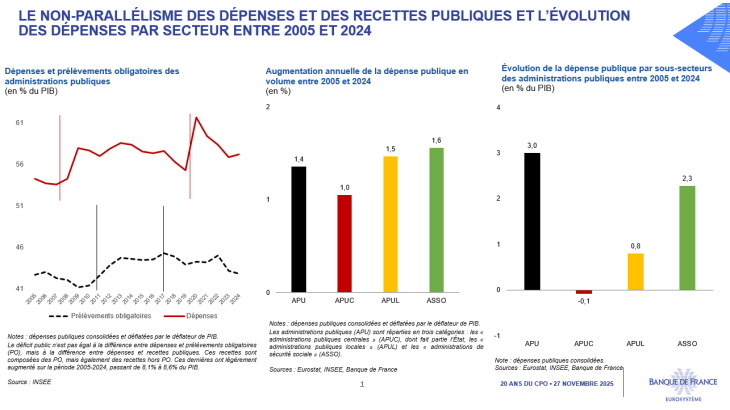

Consequently, our political debate has often focused on reducing taxes; over the past 20 years, there have been a large number of unfunded tax cuts aimed at households — on income tax or housing tax — and businesses. We must acknowledge that the political or economic benefits that were expected from these measures rarely materialised. However, our debate has concentrated much less frequently on controlling public spending, which amounted to 57.3% of GDP in 2024, compared with 54.3% in 2005. Our budgetary problem stems first and foremost from this increase, including the particularly noticeable “ratchet effect” in France after each crisis – in 2009 and then in 2020 with the Covid crisis.

We therefore need to focus most of our efforts on spending in order to achieve fiscal consolidation. Very often, the political debate centres on central government, which accounts for a large third of public spending, but local authorities, which account for 20% of the total and social spending, at 45% of the total, has grown significantly faster over the past 20 years. Since 2005, the rise in pension spending alone accounted for more than half of the increase in public spending.

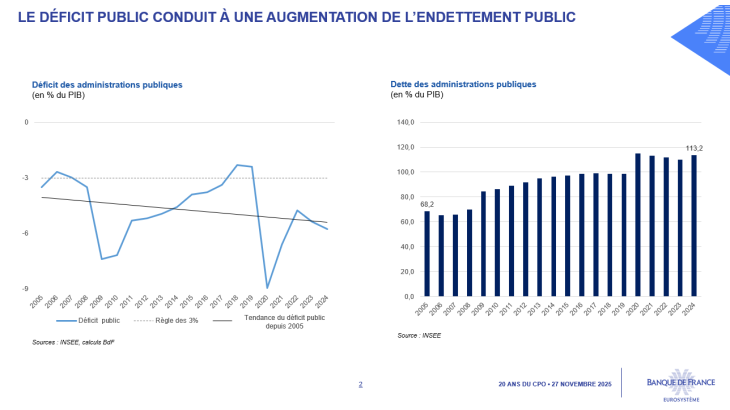

This “non-parallelism” between expenditure and revenue has widened deficits and led to the continued growth of our public debt. [Slide 3] The latter has almost doubled as a share of GDP over the past twenty years, exceeding 113% of GDP at the end of 2024, and it will probably be close to 116% at the end of 2025.ii

2. A spatial perspective

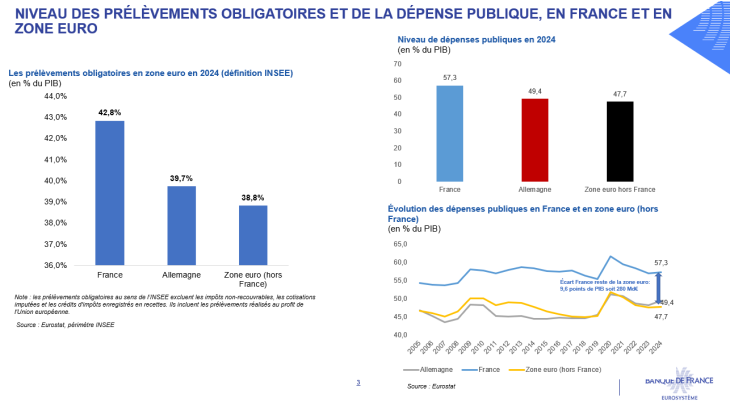

The gap between France and the euro area in terms of taxes and social security contributions is well known. In 2024, the rate of taxes and social security contributions was 42.8% of GDP in France, compared with 38.8% in the euro area excluding France, a difference of 4 percentage points of GDP.

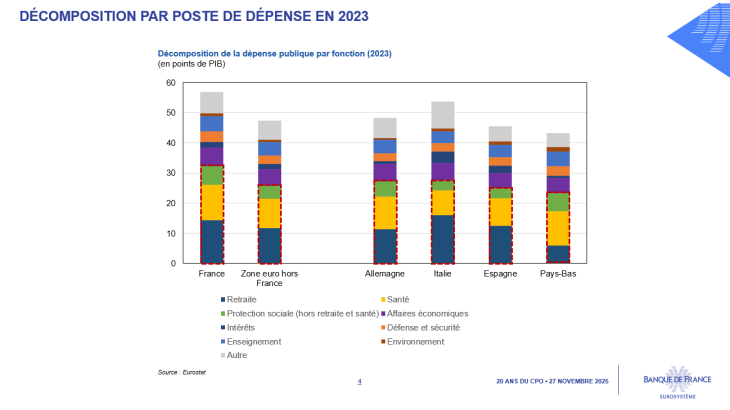

But one gap can hide another, and in our French illness we too often confuse the symptom — high taxes — with the cause — spending. Our country displays the highest level of public spending in the euro area, along with Finland. The gap in public spending with the euro area (excluding France) is even greater, at around 9.6 percentage points of GDP in 2024, which represents EUR 280 billion. This differential reflects an “efficiency gap”: we share roughly the same European social model as our neighbours, but it costs us more. In 2023, social protection spending accounted for two-thirds of this gap, while the remaining third was attributable to the higher weight of certain sectors (economic affairs, education).

The cure lies in the quality and efficiency of public spending, which too often remains the blind spot in our budget debate. The goal is to move closer to the “efficiency frontier” of public spending, which represents the ratio between public spending in each area and one or more international performance indicators. iv

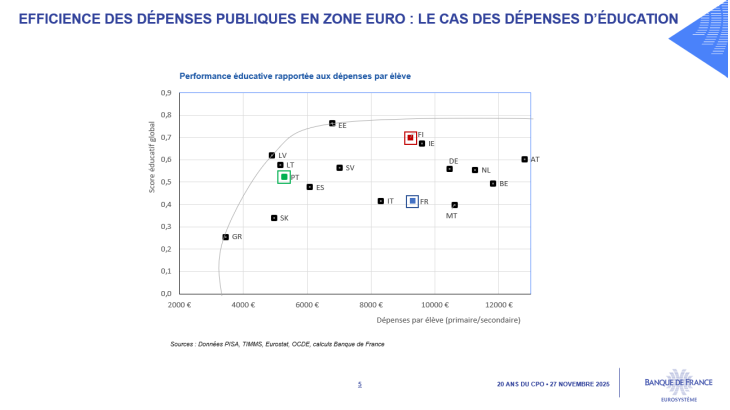

Let's take a concrete example: in terms of education spending, the order of magnitude of spending per student is comparable in France and Finland, while performance — measured by several internationally recognised v — is higher among Finnish students. In contrast, Portugal stands out with a lower level of spending per student than France, with comparable — even slightly higher — results and clear progress.

3. A praise of tax wisdom

We could debate at length about the ideal tax system, its economic incentives, and its redistributive effects. France has a particular talent for this kind of debate, with constant tax creativity, especially in autumn. I have always been very committed to tax fairness and to a fair contribution from the weathiest. However, I believe it is essential to remember that seeking the perfect, even magical, tax system is a pipe dream. Taxation cannot do everything, and genuine tax modesty must be characterised by three other virtues in addition to fairness:

- Neutrality: a good tax is one that generates revenue without unnecessarily distorting economic behaviour — VAT, as designed by Maurice Lauré in 1954, is a good example. More generally, it is better to tax downstream activities and results than upstream activities and production factors themselves.

- Simplicity: the proliferation of tax loopholes, exemptions, and derogations must be avoided. The best tax is, in principle, one that relies on a broad base and a moderate rate. As a simple illustration: the “practical brochure” on income tax for 2025 contained 85 pages on tax credits and reductions alone. The draft budget bill for 2026 listed 465 tax expenditures for an estimated amount of EUR 91.8 billion in 2025.

- Stability and predictability: France changes its tax system far too often from one year to the next, and even during the course of a single year, with the risk of fostering uncertainty and undermining confidence. I suggest that taxation be adjusted only once per legislative term and per tax. A stable and predictable tax system is more widely accepted and easier to understand for both citizens and businesses, and is therefore more effective in delivering on the economic and social intentions of its designers.

4. What does this mean for the current situation?

Your president, Pierre Moscovici, called the ongoing parliamentary debate “astonishing.” While I don’t have his talent for adjectives, I'd say that so far, this debate has been worrying and divisive. It should lower uncertainty and bring us closer to a budget for 2026, but instead, it is just adding to the confusion. It should reduce deficits, aim for spending efficiency, and contribute to fiscal wisdom — which is what French citizens expect, according to both the barometer presented this morning and opinion polls — but the discussions have so far led to more spending, more taxes and more debt, with the all too easy illusion that “others will pay”: the others being future generations, or hypothetical deep and painless pockets.

The Banque de France is not, of course, the budgetary authority, and it is not its place to comment on the details of the measures. But it is legitimate for it to be concerned about the overall economic balance and to shed light on the future of our country thanks to the complete independence of its assessment. France needs a budget, but not just any budget: the national interest imperatively calls for us to move beyond the current spectacle to find compromises and adopt a less short-term view. The persistent successes of our European neighbours show us the way. In this spirit, I would like to share three simple convictions:

- Our country must and can reduce its deficits. We must be at a maximum of 3% of GDP by 2029, in four years' time, in order to meet our European commitments but above all to finally stabilise the debt burden. The credibility threshold for the next budget is to cover a quarter of this distance, and thus reduce the deficit to 4.8%.

- Our country must and can aim to stabilise its total public spending in volume terms, after taking inflation into account. Looking at our European neighbours, we can see that this is possible without jeopardizing either our social model nor our growth. The French State must set an example, but it cannot do so alone: social and local spending must be part of an effort shared by all.

- Our country must and can make taxation both fairer and more stable. There are obvious measures that can be taken to ensure fairness: those concerning asset-holding companies, certain tax loopholes, the tax advantage enjoyed by the wealthiest retirees. As long as the deficit has not fallen below 3%, targeted and exceptional measures can be justified, for example, on the profits of large companies. But for the rest, the wise thing to do is to stop playing with taxation. We don't have the money to lower taxes, and we don't have the leeway to raise them. Since fiscal stability is a necessity, let's also make it a virtue.

*

I will conclude with La Fontaine. At a conference organised by your partner institution the High Council of Public Finance, back in May 2022, I quoted a little-known fable, The Swallow and the Little Birds. “To instincts not our own we give no credit, and till misfortune comes, we never dread it”. Having failed to sufficiently anticipate them, we are now experiencing fiscal woes, and they are severe. And the longer we think we can wait, the worse they will get. This is truly no longer the time for arguing; it must finally be the time for awakening.

iIFOP (2023). Le regard des Français sur les impôts au regard des services publics rendus - Ifop Group. 15 May.

ii According to the 2026 draft budget bill (Le rapport économique, social et financier (RESF) 2026 est publié | Direction générale du Trésor public) debt is expected to reach 115.9% of GDP by the end of 2025.

iiiEn 2023, sur les 9,5 points de PIB d’écart entre France et ZE hors France, 6,3 points sont expliqués par les dépenses sociales (soit 67% de l’écart).

ivVilleroy de Galhau (F.) (2024). Overcoming current challenges in public services | Banque de France. 10 December.

vIndicators from PISA, TIMMS, Eurostat, the OECD, and surveys, among others. Calculations by the Banque de France.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 28th of November 2025