- Home

- Governor's speeches

- Overcoming current challenges in public ...

Overcoming current challenges in public services

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 10th of December 2024

Conference on “Central banks as political players?”, Paris, 5 December 2024

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am delighted to open – here in the Jacques Delors amphitheatre – this conference organised by Banque de France around the question of “Central banks as political players?” I would like to warmly thank all members of the Historical Committee, in particular Michel Margairaz and Olivier Feiertag, whom we will have the chance to listen to today, among other historians. We have always been wary of this question because in the distant past, the Banque de France and its “regents” were sometimes criticised for their presumed “political” influence. Fortunately, times have changed and the Banque de France now belongs to all French citizens. This independence from political power is now well asserted and – better still – widely recognised.i Obviously, it is not “self-attributed” but stems from democratic power with a specific mandate, namely price stability. Incidentally, as we are in a silent period, I will not talk about monetary policy today.

Consequently, the Banque de France does not position itself as a political player even though it is a key public player: it strives to provide the best services on the ground at the lowest cost. Now more than ever, it aims to be a catalyst for inclusion through its battle against inflation and overindebtedness and its role in promoting financial literacy; to reduce uncertainty through its economic surveys and forecasts and its financial supervision; and to be a long-term stakeholder through its commitment to the climate.

But today I invite you to take the opportunity of this historical conference to take both a step back from ongoing budgetary and parliamentary events – however weighty they may be – and a step to the side: central banks can be seen as careful observers of the current challenges facing public services, if only through the consequences of fiscal policy on the policy mix, the second ingredient of which is monetary policy. I am also going to speak as someone who is passionate about public service and who believes profoundly in the European social model. This unique combination of universally accessible essential services, strong social protection and tax redistribution has produced – particularly in our country – some of the most cohesive societies in the world, and some of the most competent public authorities. However, visible difficulties are increasing in almost all advanced countries, and particularly in our own, public action is becoming more and more extended and expected, less and less well financed and financeable, and often perceived as less and less effective. This is why I would like to present an “anatomy” of these challenges in France, first over time for the purpose of understanding them (I), and then from a spatial perspective, for the purpose of taking action (II).

I. Understanding: an anatomy over time

1.1. A concomitant but non-convergent increase in public spending and revenue has fuelled a continuous deterioration in our public finances

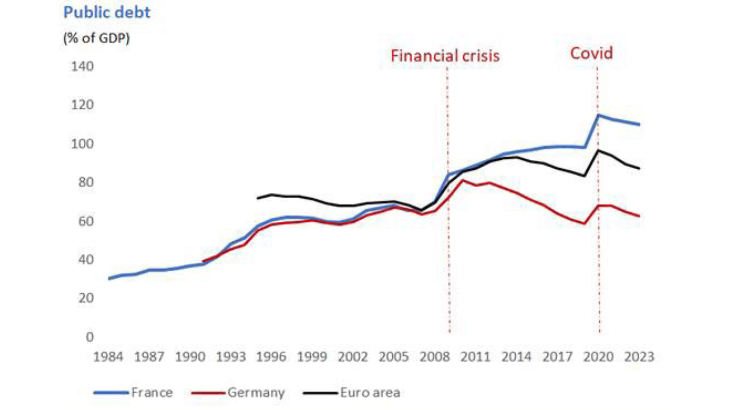

Our public finances have been steadily deteriorating for over forty years. In 1984, our public debt represented just 30% of gross domestic product (GDP); today, it has more than tripled to 110% of GDP.

OUR PUBLIC FINANCES HAVE MARKEDLY DETERIORATED

This proportion fell only slightly after the Covid shock, and now stands more than 20 points above the euro area average (87%), and almost 50 points above that of Germany (63%). This is largely due to the fact that public spending has been rising faster than revenues. This “non-congruence” generates systematic structural deficits, which drive the increase in public debt. And this leads us to remember the obvious: regardless of the political situation, France needs to put its public finances in order. This is in our national interest, which transcends partisan interests.

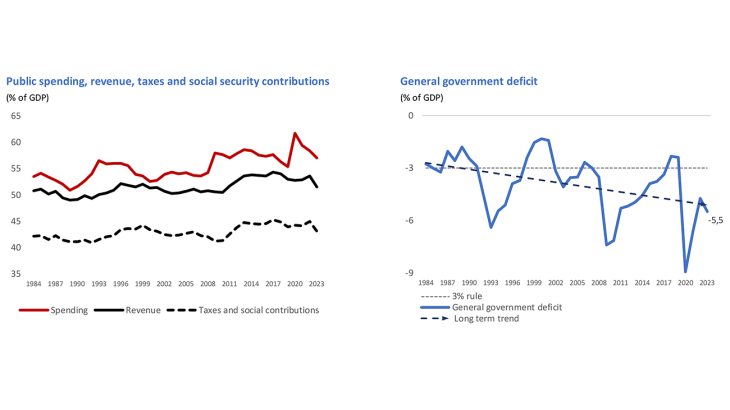

THE "NON-CONGRUENCE" IN PUBLIC SPENDING AND REVENUE

Our problem is due primarily to the growth in our public spending. Beyond a “ratchet effect” that is particularly marked in France after each crisis, it is above all the rise in welfare and local spending that has fuelled this increase over the past thirty years. As regards local spending, this increase goes beyond the transfer of powersii, but in the meantime, fiscal revenue transfers from the central government – including a proportion of VAT – have increased dynamically, so that the rise in spending is not immediately noticeable in the financial balances of local authorities.

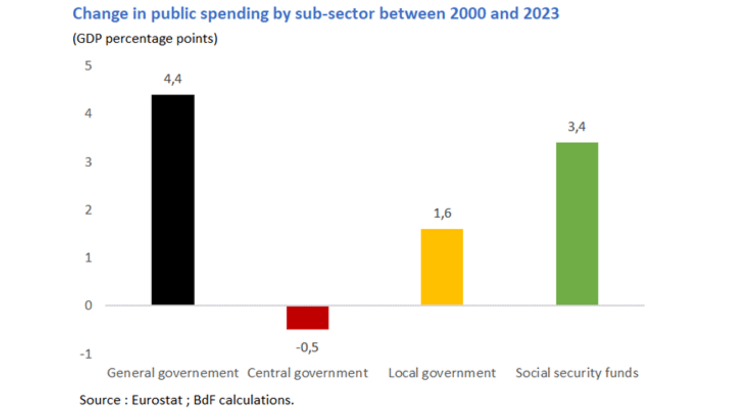

WHERE HAS THE INCREASE IN OUR PUBLIC SPENDING COME FROM?

Source : Eurostat ; BdF calculations

Indeed, spending by social security funds and local government bodies grew by 3.4 and 1.6 percentage points of GDP, respectively between 2000 and 2023. In contrast, central government expenditure fell by 0.5 percentage points of GDP over the same period.

1.2. This deterioration is compounded by a concomitant increase in what French citizens expect from the state and in the complexity of public action

On the one hand, our fellow citizens have increasingly high expectations of the state, many of which are justified on objective grounds. I am convinced that public authority must respond to the long-term challenges facing France and Europe, such as climate change, security and an ageing population.iii Some of these expectations are also subjective, as a result of the precautionary principle inter alia. We have handed the state an increasingly important role as “insurer of first resort” in the face of crises (think Covid or the inflationary episode of 2022), as well as risks of all kinds, including accidental risks, without taxpayers – companies and households – really being prepared to collectively contribute to this insurance via their taxes. In response to changing expectations, the state has turned into an ex post repairer, including of ex ante failures in public policies. Compensation for shortcomings in the labour market and training is a good example: for the past 30 years, private-sector employment has been supported by a stack of reductions in social security contributions. These exemptions now cost us 2.7 percentage points of GDP, compared with just 1 percentage point in 2012, and 0.5 percentage point in 1999.

On the other hand, public action has become much more complex. This complexity is difficult to measure but we can gauge it from a number of indicators.

The number of standards introduced by the state is constantly increasing. To give a very concrete example, the number of words on the French government website Légifrance, listing the standards in force in France, has doubled in twenty years, from 23 million in 2002 to 45 million in 2023.iv This “inflation” in standards discourages initiatives and adds to the administrative burden on households and business owners, representing an estimated annual cost of between 3% and 8% of our GDP.v

This increasing complexity is also affecting our administrative structures. I will take two examples: local administration, and government operators. Over the past forty years, the process of decentralisation has resulted in an unprecedented tangle of responsibilities and powers at local authority level.vi This administrative patchwork generates considerable coordination costs and undermines the clarity and legitimacy of the many players involved, particularly at intermunicipal level. With almost 370,000 employees, the latter now represent 19% of the local government workforce,vii without any corresponding reduction in the number of municipal employees. However, their role is not sufficiently clear for the general public, who tends to think that “everything gets done by everyone”.viii Moreover, despite the extensive streamlining that began in 2013, there are still too many government operators (434 at present,ix employing a total of almost 500,000 people ), with a heavy resulting oversight burden.

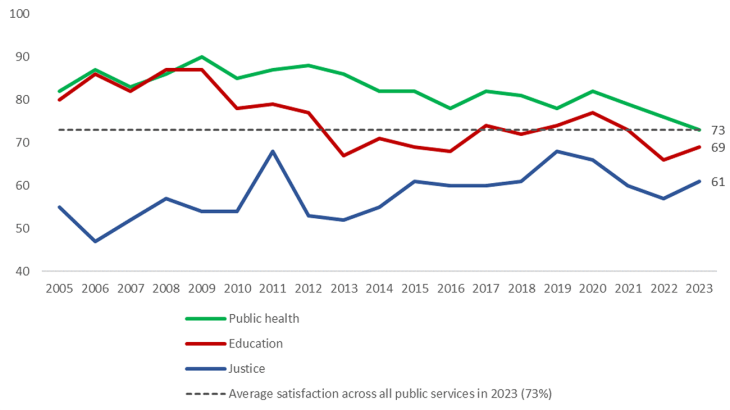

A “fiscal allergy” therefore risks being compounded henceforth by a “bureaucratic allergy”. A number of public services have been contending with a crisis for several years, along with decreasing satisfaction among French citizens:xi over the past fifteen years, this has been particularly acute in health and education (where a decline in satisfaction of almost 20 percentage points has been recorded). Despite a recent improvement, justice remains the public service for which user satisfaction is still significantly low. This impression that public services are going downhill is often put forward as a contributor to the rise in the protest vote in numerous countries.xii

THE SATISFACTION OF FRENCH CITIZENS WITH THEIR PUBLIC SERVICES

These French “allergies” also reflect a contradictory desire for more government but less tax and fewer rules. Frédéric Bastiat's famous quote, “The state is that great fictitious entity by which everyone seeks to live at the expense of everyone else”, is thus strikingly apposite today. These contradictions are weighing more and more heavily, not only on our public finances but also on our political debate. All too often, some people are tempted to resolve them by “civil servant bashing”. But it is by working with civil servants and managers, not against them, that we will succeed: while being demanding of civil servants is legitimate, systematic and often demagogical criticism of them is not. Unfortunately, we are currently witnessing an extreme example on the other side of the Atlantic.

II. Action: a spatial analysis

2.1 Overall, there is no evidence that “public production” is better in France

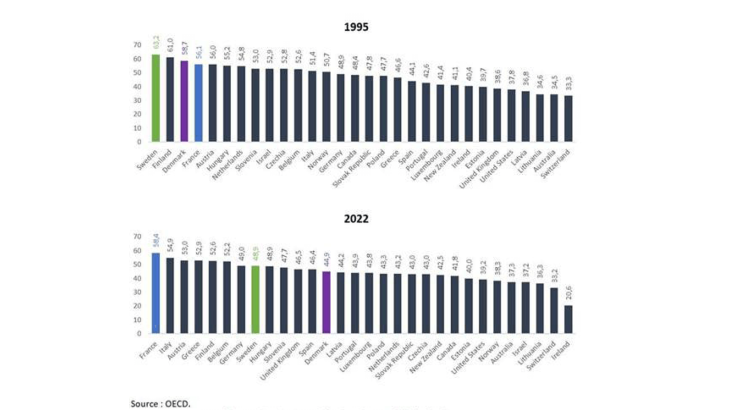

Of course, many of these symptoms can be found in other OECD countries – and in many respects, Italy most closely mirrors our situation – however they are most acute in France. Let us take Denmark and Sweden as benchmarks. Between 1995 and 2022, Germany and Sweden reduced their government expenditure ratio from 59% to 45%, and from 63% to 49%, respectively. Meanwhile, our country has gone from fourth to the top of the table in terms of government expenditure.

OECD RANKING - PUBLIC SPENDING

Source : OECD.

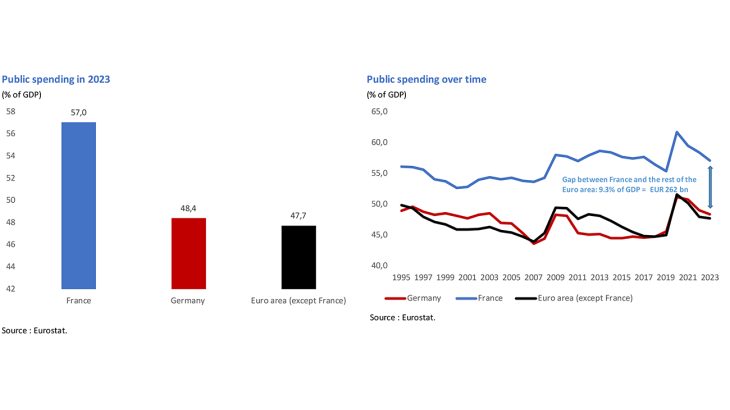

Government expenditure in France, at around 57% of GDP in 2023, xiii is 9.3 percentage points of GDP higher than the average for the euro area excluding France – a gap of around EUR 260 billion. For all that, is public production better in France?

A HIGH LEVEL OF PUBLIC SPENDING COMPARED WITH OUR NEIGHBOURS

Source : Eurostat.

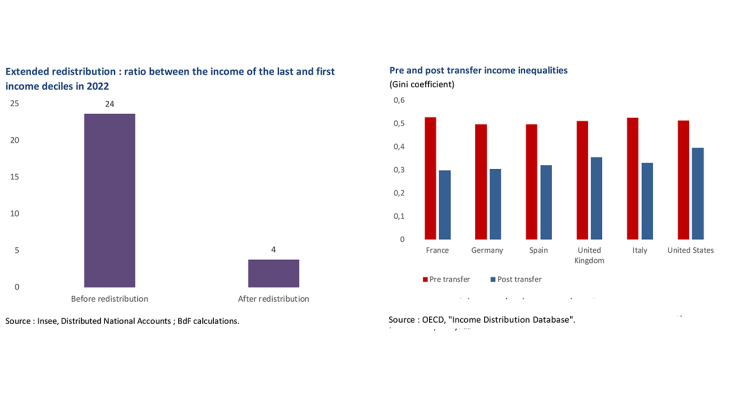

Certain objective outcomes are positive. Inequalities continue to be more contained in France than in our neighbouring economies, and even more so than in the United States. In its first “augmented national accounts”, INSEE estimated that the extended redistribution (all transfers including those associated with public services) in France reduces the income ratio between the wealthiest 10% and the poorest 10% by a factor of six before and after transfers. Consequently, the French Gini coefficient after transfers, is among the lowest.

INEQUALITIES IN REVENUE, BEFORE AND AFTER TRANSFERS

Source : OCDE, "Income Distribution Database".

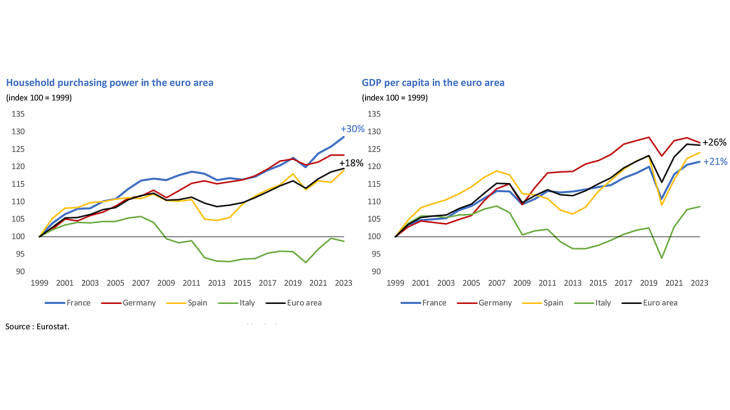

Our level of public investment is significantly higher than that of our neighbours (4.3% of GDP in France, compared with 3.3% for the euro area as a whole, and 2.8% in Germany) and this is apparent in the quality of our roads and infrastructure. And public spending has protected households and businesses against a succession of economic shocks following the 2009 financial crisis. For a long period, household purchasing power rose more markedly in France than in the euro area as a whole (by a cumulative 30% since 1999, compared with only 18% for the euro area), even though public perception is nowhere near as favourable.

By contrast, there is less growth in France: GDP per capita has risen more slowly in France, by a cumulative 21% between 1999 and 2023 compared with 26% in the euro area as a whole, which itself lags considerably behind the United States (up 39%) in terms of growth.

COMTRASTING TRENDS IN PURCHASING POWER AND PER CAPITA GROWTH

Source : Eurostat

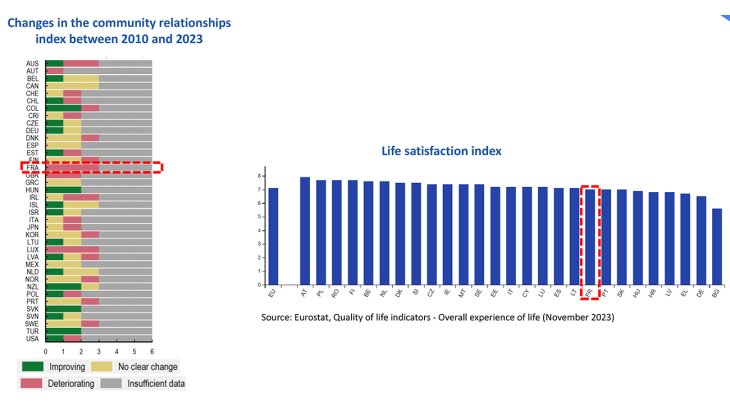

Furthermore, our government expenditure has not created more jobs than in neighbouring countries: in France, the unemployment rate remains higher, and the employment rate lower, than in the euro area as a whole, despite improvements in the labour market over the past decade or so. Last and most importantly, social cohesion and life satisfaction are no better in France than elsewhere. Between 2010 and 2023, the OECD social cohesion indicator deteriorated more sharply for France than for any other country.xvi And France's life satisfaction index, at 7 on a scale of 1 to 10, stands slightly below the European Union average of 7.1.xvii Here we touch on the promising research into the “economics of happiness” or “well-being” xviii, and its paradoxes, especially by Richard Easterlin (relative comparison counts for more than absolute prosperity).

SOCIAL COHESION AND LIFE SATISFACTION

Source : OECD (In brief : How's life? 2024)

2.2 This landscape may appear bleak... but these comparisons are actually opportunities for action and grounds for hope

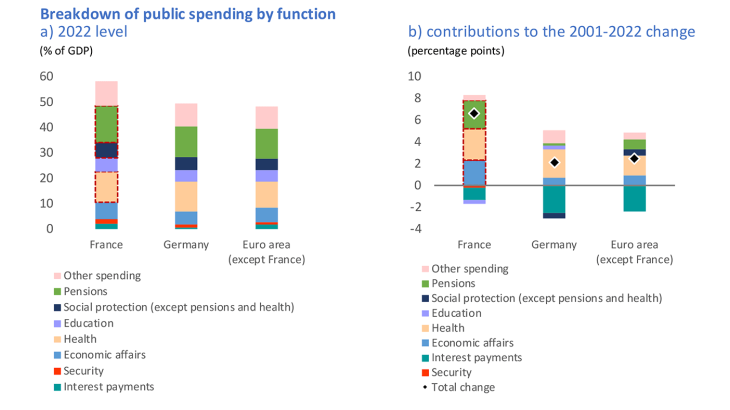

We can draw positive lessons from the experience of our neighbours, who have succeeded in reining in and even reducing their government expenditure while preserving their social model and maintaining growth.xix This leads me to consider the composition of our own government expenditure and to compare our spending with that of the best-performing economies

BREAKDOWN OF PUBLIC SPENDING AND TRENDS BY CATEGORY

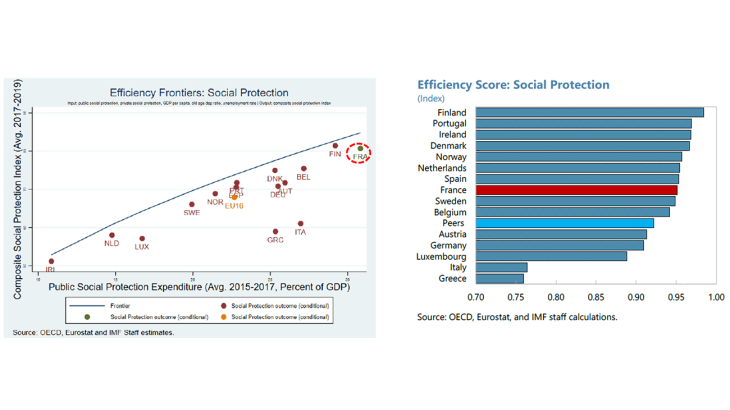

Obviously, the Banque de France is not a decision-maker when it comes to choices in expenditure, which are a matter for democratic debate. International comparisons help to inform the debate, however the work of France Stratégie,xx the European Commission, xxi the OECDxxii and the IMFxxiii in this regard continues to be surprisingly little-known. Among other things, they make it possible to define an “efficiency frontier” for public spending, by comparing the relationship between each category of public expenditure and one or more international performance indicators in different countries. These “frontiers” raise methodological questionsxxiv, but also provide valuable insights.

FRENCH SOCIAL SPENDING:

THE HIGHEST - AND RELATIVELY EFFICIENT

France’s spending on social protection in the broadest sensexxv is significantly higher than the euro area average excluding France, at around 6.3 points of GDP in 2022 – or more than half of the total gap. Admittedly, some of this can be explained by different pension systems and the choice of pay-as-you-go rather than funded systems (capitalisation). However, in its analysis published in early 2023, the IMF reported that France, despite having the highest spending on social protection out of a sample of fifteen comparable countries, is further from the efficiency frontier than Finland, Portugal, the Netherlands or Denmark. France is barely above average in terms of its spending efficiency. Indeed, some transfers are means-tested to a lesser extent than in other countries, which explains the comparatively weaker redistributive effect of its social protection spending.

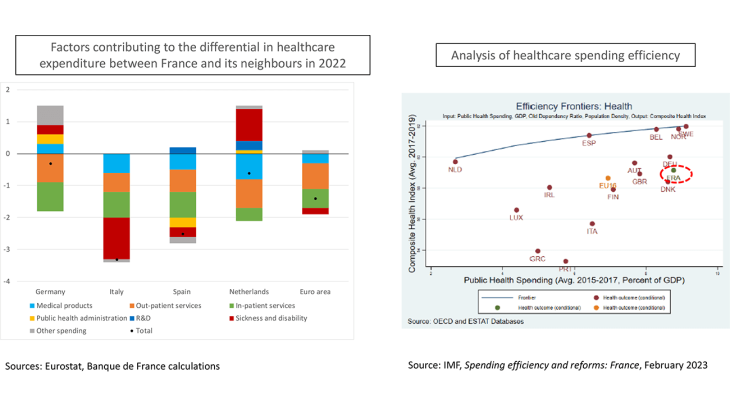

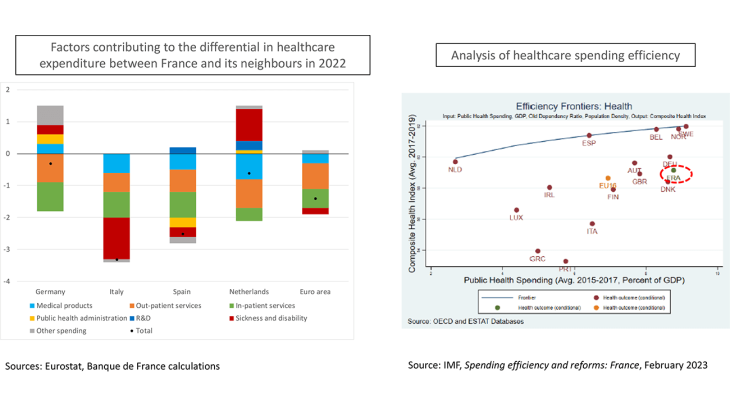

In this overview, I will not revisit the better-known examples of spending on pensions – which accounts for the most significant differential – or unemployment benefits. But it is instructive to consider the example of spending on healthcare, which accounts for 1.9 percentage points of the total gap between France and the rest of the euro area.

HEALTHCARE EXPENDITURE: IMPERFECT EFFICIENCY

Source : Eurostat, Banque de France calculations

Source : IMF, Spending efficiency and reforms: France, February 2023

We have significant possibilities for improvement compared with countries such as Spain, Sweden, Belgium or the Netherlands, with higher spending for comparable results across key indicators (healthy life expectancy, healthcare system satisfaction, etc.). There are also more workers in public administration: they account for 34% of the total workforce in the hospital sector, compared with 23% in Spain and 21% in Germany. Furthermore, in other countries, medical systems that focus more on prevention improve healthy life expectancy and limit the incidence of chronic diseases.

Spending on education is 0.7 percentage point of GDP higher than the euro area average excluding France, partly due to the higher proportion of the population attending school in France.xxvi However, the way this expenditure is allocated between primary education (under-resourced compared with other countries) and secondary education (relatively over-resourced in comparison) is rather atypical. The proportion given over to administrative and operating costs is significantly higher than in other countries (see the dark blue component in the left-hand chart below). Our high level of spending did not prevent a sharper decline between the PISA 2018 and 2022 surveys. In this respect, Finland gets better value per euro spent.

EDUCATION : A HEAVY ADMINISTRATIVE BURDEN,

AND RELATIVELY UNDER-RESOURCED PRIMARY EDUCATION

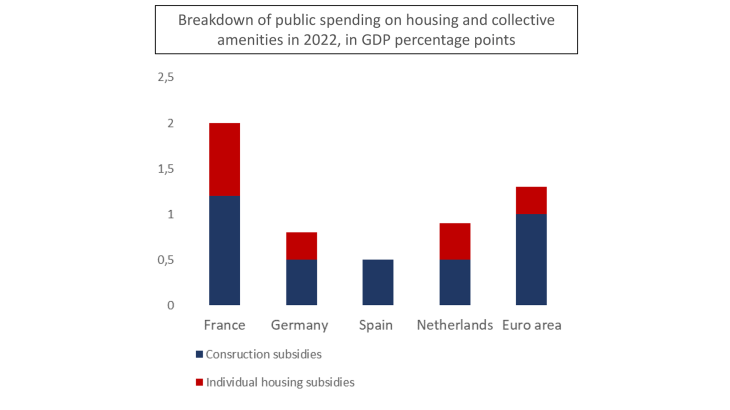

Housing, which contributes an estimated total of approximately 2% of GDP (0.8 point of GDP more than the euro area average excluding France), is also a major source of expenditure.

HOUSING: HIGHER SPENDING THAN OUR NEIGHBOURS

Six million households – one in five – currently receive housing benefits, which therefore appears to be means-tested to a much lesser extent than in other countries. These substantial amounts can ultimately push up market prices – including rents. On top of this, there are numerous tax credit schemes.

The Cour des Comptes has therefore reported that France’s housing policy “struggles to demonstrate its effectiveness”.xxviii

As a final example, which partly overlaps with previous ones, subsidies and transfers (unrelated to social protection) amounted to EUR 210 billion in France in 2023, that is 7.4% of GDP compared to an average for the rest of the euro area of just 6.0%. Their increase in France since 1996 has contributed 2.2 points of GDP to the rise in public spending. Among this expenditure, certain tax credits and support for apprenticeship programs would benefit from being more clearly targeted. More generally, there are grounds for reviewing certain acquired rights and for de-indexation.

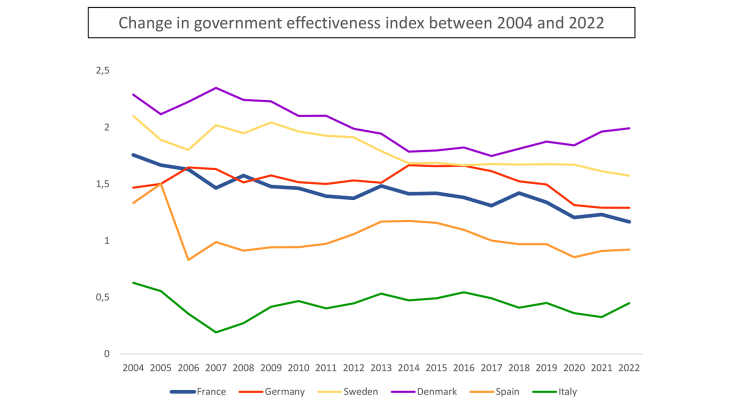

2.3 Reopening the “blind spot” in the public debate: qualitative levers and public governance

Every year, the World Bank publishes an index of government effectiveness,xxix which draws from a range of studies and surveys.xxx In particular, it focuses on the degree of independence from political pressures, public policy formulation and implementation, and the quality of public services. France's government effectiveness score has slowly but steadily declined since the beginning of the 2000s, dropping from 1.75 in 2004 to 1.16 in 2022 (over a distribution ranging from -2.5 to +2.5). In the 2010s, Denmark managed to reverse a similar downward trend, pushing its score back up to a high level of 2 in 2022. We can thus assess the qualitative levers that we can deploy.

WORLD BANK GOVERNMENT EFFECTIVENESS INDEX

Several attempts have been made to reform government action, from the Organic Budget Law (LOLF) of 2001, which aimed for performance-focused management, to the more recent Action Publique 2022. Buy-in and the results obtained have generally fallen short of expectations.

I am well aware of how difficult it is for successive governments to deal with the unrelenting pressure of urgency, exacerbated by a succession of unprecedented crises. But far from being some fatalistic pessimist, I believe in public services as a national asset. Throughout our long history, from Bonaparte to Charles de Gaulle, public services have frequently been a catalyst for unity, modernity and even productivity. I also believe that they can be turned around. Transforming public services can and must serve to boost France’s competitiveness. These are not merely pious hopes: examples of successful public service modernisation exist in France. Aside from the example of the Banque de France, which I mentioned in my introduction, we should mention the Public Finances Directorate (Direction Générale des Finances Publiques, DGFiP), which has improved the quality of the service it provides, particularly to private individuals, while at the same time achieving significant economies of scale by pooling its support functions (headcount was reduced by 29% between 1998 and 2023).xxxi Of all public services, taxation and tax collection now have the highest customer satisfaction rating at 80%.xxxii

A strategy for public finances and ambitions for government action are not incompatible. On the contrary: “reconciling the dynamics of modernisation with the imperative of restoring balance to public finances is essential”. The path of compatibility must include four aspects, on which central banks can offer instructive lessons.

The first essential aspect is long-term thinking and continuity. Management of public finances is now based more on a multi-year perspective – which is a good thing – with the adoption of public finance planning acts from 2009 onwards. However, when it comes to executing the process, we have never honoured our commitments. And it takes time, patience and tenacity to achieve savings in public spending. It would therefore be desirable for the medium-term – through 2029 – fiscal consolidation plan, which is more necessary than ever, to include a more significant and better-documented savings component.

This brings us to the second aspect – effective implementation by public-sector participants. In this respect, the central plank of effective governance is “contractualisation” matched by “responsibilisation” – i.e., respecting the allocated resources and achieving the mutually agreed objectives. The Cour des Comptes rightly recommends following this method,xxxiv drawing on past examples from INSEE and DGFiP. I can also vouch for its effectiveness as a practitioner. France still boasts excellent civil servants and public service managers: let us delegate responsibilities and resources to them, within a multiannual framework, in exchange for more clearly defined objectives. Many public servants are ready; all they ask for is this trust and freedom.

The third aspect is an essential vector for the transformation of public services; one which we are all expecting but which has all too often been neglected – simplification. An over-abundance of regulations reduces competition, discourages entrepreneurs and hampers productive investment. Today, there is a new consensus in principle in Europe in favour of simplification. The Draghi report,xxxv following the Letta report,xxxvi identified the simplification of rules as one of the keys to European competitiveness and a more effective state. We need to learn to regularly "take a broom" to those constraints that are vestiges of the past or no longer useful. Although this calls for a massive, structured and costed simplification effort, it is possible and it will meet the high expectations of citizens and SMEs alike.

The final aspect is clarity of objectives ex ante and of actual results ex post. What undermines government action and makes our fellow citizens so sceptical is the proliferation of announcements in the media that have not resulted in any effective action, and of plans and objectives that are rarely prioritised and are often contradictory. Less talk, more accountability for genuine action: this dose of realism would do us all good.

iLaw of 4 August 1993 on the status of the Banque de France and on the activities and supervision of credit institutions.

iiFipeco, Pourquoi et comment réduire les effectifs de la fonction publique, 9 July 2024

iiiECB, “Longer-term challenges for fiscal policy in the euro area “, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, 2024

ivEoche-Duval (C.), L’inflation normative, Plon, 2024

vSenate, Rapport d’information Devinaz-Moga-Rietmann sur la simplification des règles et normes applicables aux entreprises, June 2023

viCour des comptes, “La décentralisation 40 ans après : un élan à retrouver “, Public Annual Report, March 2023

viiMinistry for the public service, simplification and transformation of public action, L’évolution des effectifs dans la fonction publique en 2021, 15 December 2023

viiiInspection générale des finances, Rapport Ravignon sur le coût du millefeuille administratif, May 2024

ixFrench government, Projet de loi de finances pour 2025 (Budget law for 2025)

xAnnexe au projet de loi de finances pour 2025 (Appendix to the draft budget law for 2025), Opérateurs de l’État

xiInstitut Paul Delouvrier, Baromètre 24e édition, December 2023

xiiSee for example, Hélène Rey in Les Échos, Les mystères du vote populiste, 13 February 2020

xiiiINSEE, Le compte des administrations publiques en 2023, 5 November 2024

xivINSEE, Croissance, soutenabilité climatique, redistribution : qu’apprend-on des « comptes augmentés » ?, 5 November 2024

xvVilleroy de Galhau (F.), France and Europe: from crisis management to longer-term ambition, 21 April 2024

xviOECD, In brief: how’s life? 2024, 5 November 2024

xviiEurostat, Quality of life indicators – overall experience of life, November 2023 data

xviiiCEPREMAP, Observatoire du Bien-être, founded by Claudia Senik

xixConseil d’analyse économique (CAE), Quelle stratégie pour les dépenses publiques ?, July 2017

xxFrance Stratégie, Pourquoi les dépenses publiques sont-elles plus élevées dans certains pays ?, July 2014

xxiEuropean Commission, Efficiency estimates of health care systems, June 2015

xxiiOECD, Public spending efficiency in the OECD: benchmarking health care, education and general administration, February 2016

xxiiiInternational Monetary Fund, Spending efficiency and reforms: France, 28 February 2023

xxivFrance Stratégie, ibid; notably pages 2 and 3 concerning methodological questions related to “efficiency frontiers”

xxvIncluding pension, healthcare, family, unemployment and personal housing benefits

xxviThe proportion of the population attending school is 23% in France compared with an average of 20.5% for the euro area as a whole

xxviiCour des Comptes, Restaurer la cohérence de la politique du logement du logement en l’adaptant aux nouveaux défis, November 2021

xxviiiCour des Comptes, Assurer la cohérence de la politique du logement face à ses nouveaux défis, note thématique, July 2023

xxixWorld Bank, Worldwide governance indicators

xxxIn assessing the government effectiveness of France and the other European countries in 2022, the World Bank drew on eight sources: The Economist Intelligence Unit; the European Quality of Governance Index; the Gallup World Poll; the Institute for Management and Development World Competitiveness Yearbook; the Political Risk Services International Country Risk Guide; S&P Global Country Risk Service; World Bank Enterprise Surveys; and the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report

xxxiWorkforce at 1 January 1998 (prior to the merger of the DGI (Direction générale des impôts) and the DGCP (Direction générale de la comptabilité publique), compared to the DGFiP workforce of 95,000 in 2023.

xxxiiBaromètre Paul Delouvrier 2023 ; see trends in public service user satisfaction

xxxiiiCour des Comptes, La modernisation de l’État : des méthodes renouvelées, une ambition limitée, 26 January 2024

xxxivCour des Comptes, ibid

xxxvDraghi (M.), The future of European competitiveness, report, September 2024

xxxviLetta (E.), Much more than a market, report, April 2024.

xxxviiReported by Alain Peyrefitte in C’était De Gaulle, volume II, published in 1997

Download the full publication

Updated on the 10th of December 2024