Most macroeconomic models are based on the hypothesis of full information rational expectations. However, empirical facts tend to reject this hypothesis and highlight the strength of information frictions. Documenting these information frictions is crucial for central banks as they may have a strong influence on the effects of monetary policy on the economy.

As macroeconomic dynamics depend on expectation processes, monetary policy consists for a large part in managing inflation expectations of different agents (households, firms, professional forecasters). It is therefore of utmost importance for central bankers to measure inflation expectations (see Bouche et al., 2022) and to determine the strength of informational frictions that affect these expectations.

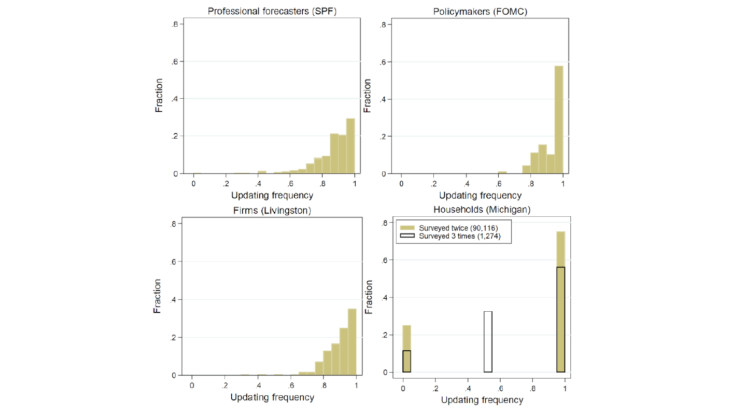

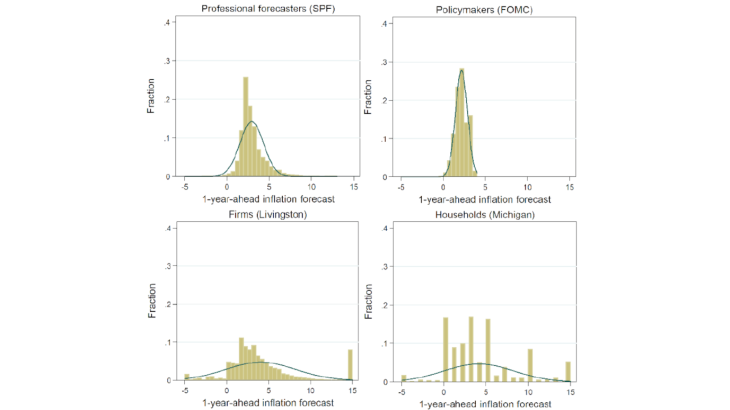

These informational frictions can be characterized by the frequency of forecast revisions (the lower the frequency, the higher the friction) and cross-sectional disagreement on inflation expectations (the larger the dispersion, the higher the friction). Andrade and Le Bihan, 2013, Coibion and Gorodnichenko, 2015, and Savignac et al., 2021 discuss these dimensions for some economic agents.

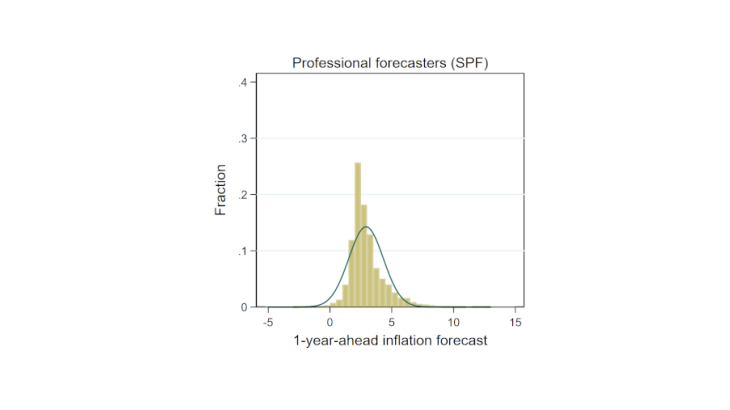

For instance, the disagreement on inflation expectations appears small for US professional forecasters (most of the inflation forecasts are comprised between 1 and 3%, see Figure 1). However, this measure needs to be compared to other economic agents to be properly assessed. Because the cost of collecting and processing information may be different for individuals, the strength of information frictions could vary dramatically within and across various categories.

In a recent work, Cornand and Hubert, 2022 focus on two dimensions of these frictions: the frequency of forecast revisions and the cross-sectional disagreement in inflation expectation surveys among and within four categories of US economic agents: households (Michigan Survey), firms (Livingston Survey), professional forecasters (Survey of Professional Forecasters of the Philadelphia Fed) and policymakers (FOMC members). By harmonizing the characteristics of different surveys to make them as comparable as possible, it is achievable to compare the frequency at which individuals revise their inflation forecasts and the cross-sectional disagreement on these inflation forecasts for households, firms, professional forecasters and policymakers in the United States (US).

Economic agents experience information frictions but with different relative strength

All economic agents experience information frictions. However, a strong heterogeneity in their relative strength can be documented. Figure 2 plots the frequency of forecast revisions across the four categories of agents. Policymakers revise more frequently (almost 60% of them always revise their forecasts, i.e. at each period) than firms and professional forecasters (for which around 30% of them always revise), who themselves revise more frequently than households. Note that this is in part –but not only– due to how the survey is conducted: households are only observed twice or thrice and then are dropped out of the survey. We also find that the frequency of forecast revisions evolves over time and is affected by the volatility of inflation.