1 Taxation on production in France: successive reforms to contain a historically high level

France has long set itself apart through a high level of taxation on production. These taxes represented, for example, 3.6% of companies’ value added in 2016 compared with 0.5% in Germany, ranking France as the second highest country for this type of tax in Europe after Greece (Martin and Trannoy, 2019). But such taxes are generally considered harmful to the economy because of the distortions they engender along the production chain. In fact, because they penalise productivity and competitiveness, they influence companies’ methods of production. Since the early 2000s, one government after another has tried to reduce these taxes, as illustrated in particular by the successive reforms of the taxe professionnelle (TP – business tax). This article looks at the effects of the removal of this tax and its replacement with the CET.

The business tax before 2010

The business tax was introduced by the law of 29 July 1975, which simultaneously abolished the “patente” taxes in place since the end of the eighteenth century. Initially, the business tax was applied using a composite tax base that included: (i) the company’s receipts; (ii) the rental value of its real estate assets liable for property tax; (iii) the rental value of its equipment and moveable assets; and (iv) its wages. In 2003, the wage component was excluded from this tax base because of its harmful effects on employment.

Until 2009, the three components – receipts, rental value of real estate assets and rental value of equipment and moveable assets – could be accrued based on a complex mix of factors (see Table 1), sometimes leading to significant threshold effects. The general tax

base penalised investment because the rental value of equipment and moveable assets and of industrial buildings subject to property tax was a direct function of their cost price. The business tax affected in particular those sectors with high capital intensity (with the highest ratio of investment to value added) despite an applied ceiling. The manufacturing, energy and transport sectors paid nearly 66% of the business tax, while they represented less than 35% of the total taxable profits of all companies.

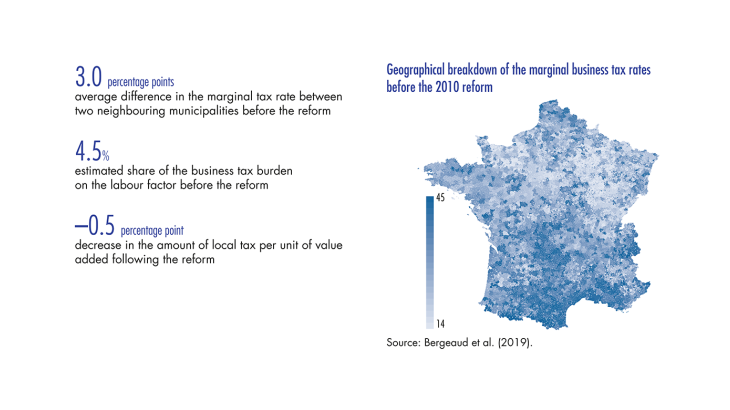

The marginal rates were set by the various local authorities (municipalities, groupings of municipalities, departments and regions). Because of the variations in these rates, a distortion of competition could occur between companies depending on where they were located, even between two neighbouring municipalities.

[to read more, please download the article]