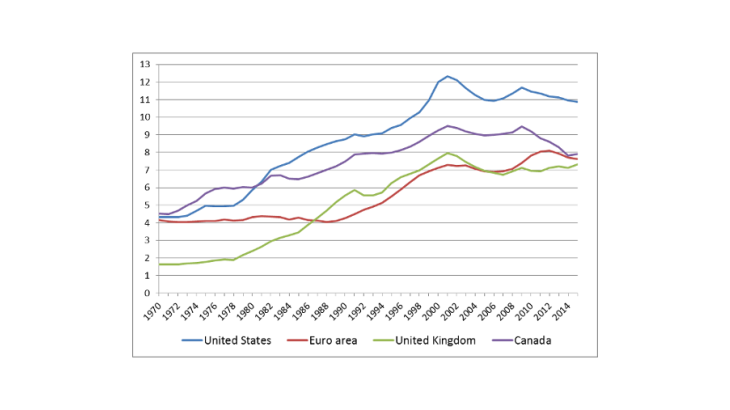

Note: Nominal ICT capital coefficient = nominal ICT capital divided by nominal GDP, economy as a whole, in %.

The low GDP growth observed in the main advanced countries since the start of the 21st century can principally be attributed to sharp falls in productivity gains – in some cases to an all-time low (see Bergeaud, Cette and Lecat, 2017). Can these trends be linked to developments in ICT diffusion (see Cette and Jullien de Pommerol, 2018)?

ICT diffusion has stabilised since the start of the 2000s

The diffusion of ICT to productive activity is captured here using the nominal ICT capital coefficient, which is nominal ICT capital divided by nominal GDP. In the United States, the euro area, the United Kingdom and Canada, this ICT capital coefficient increased steadily over the three decades from the start of the 1970s to the early 2000s (see Chart 1). It subsequently stabilised, as various studies have highlighted (e.g. Cette, Clerc and Bresson, 2015). ICT investment now consists in replacing previous ICT assets at constant value, although with steady gains in performance as ICT prices are still falling, albeit at a slower pace.

ICT diffusion has stabilised at very different levels (see, for example, Van Ark et al., 2008, Timmer et al., 2011, Cette and Lopez, 2012). The divergences are quite marked: at the end of the period, the United States' nominal ICT capital coefficient was more than 30% higher than in the three other economic areas under consideration.

Numerous studies have provided empirical explanations for these variations, such as differences in the average educational attainment of the working-age population, and the existence of rigidities in product and labour markets (see, for example, Aghion et al., 2009, Guerrieri et al., 2011, Cette and Lopez, 2012). In order to harvest the full potential of ICT, average skill levels need to be higher than for other forms of technology, and companies need to restructure, which can be difficult when labour market regulations are too strict. Certain product market regulations can also reduce competitive pressures, which can in turn lower the incentives for using better technology.

The contribution of ICT to growth has fallen

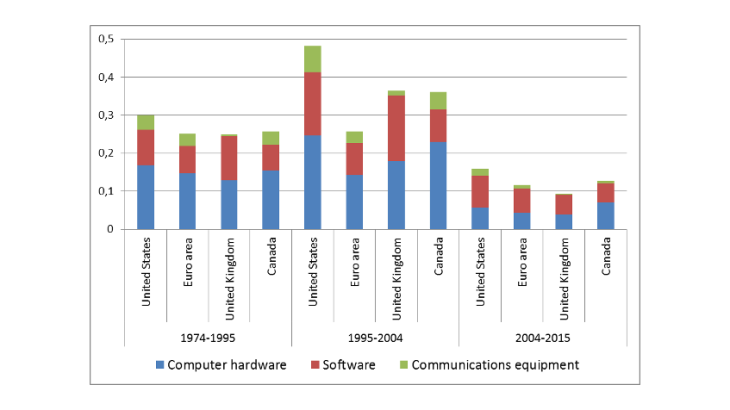

ICT can boost labour productivity via a number of channels. We focus on one of these, which is arguably the most important: the substitution of labour with ICT capital. We measure the contribution of ICT to growth in labour productivity via the increase in ICT capital intensity in productive apparatus. The period when ICT makes the strongest contribution to growth in hourly labour productivity is from 1995 to 2004. In the United States, where the contribution is highest, ICT adds an average of 0.5 percentage point to growth per year in 1995-2004, compared with 0.3 percentage point in the previous decade. This then falls back to 0.15 percentage point between 2004 and 2015. A similar, albeit more limited wave can be observed in the other countries included in our study (see Chart 2).