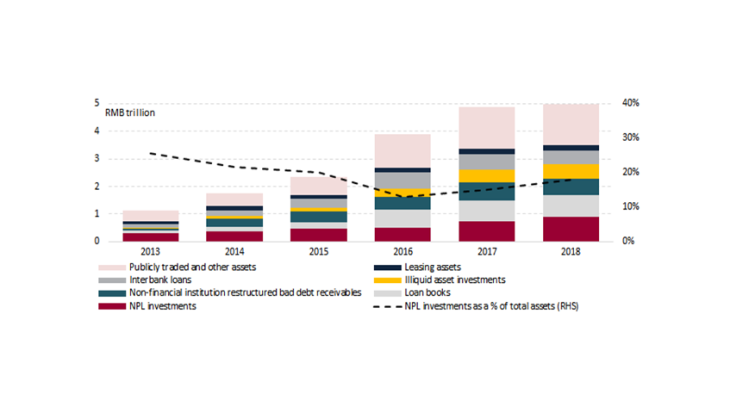

In the mid-2000s, regulatory changes allowed AMCs to start transforming into full-fledged financial conglomerates. Once their policy-mandated NPL disposals were deemed accomplished, they were allowed to purchase NPLs on commercial terms and expand into new business activities. By the early 2010s, the business model of the AMCs had changed and their subsequent balance sheet expansion (see Figure 2) was driven mostly by non-core and more profitable activities such as investment banking.

The funding and governance structure of the AMCs also changed. The AMCs were originally funded by credit from the People’s Bank of China and 10-year AMC bonds held by the state-owned banks. Their subsequent expansion largely relied on domestic credit market borrowing, as well as a 10-year rollover of the original AMC bonds. While Cinda went public in 2013 and Huarong in 2015, the big four AMCs remain mostly state-controlled.

Regional AMCs have been established since 2012, and have developed into an important policy instrument, drawing comparative advantage from established connections with local stakeholders.

The experience with Chinese AMCs provides valuable insights, especially for emerging economies with large government-owned financial and corporate sectors. It points to the inevitability of a large fiscal cost, which could however be reduced by a) upfront loss recognition and b) transparent AMC mandates, as well as by c) the parallel development of an active secondary NPL market. While the initial goal of the Chinese AMCs has mostly been achieved, shortcomings in fulfilling these crucial elements make their usefulness less certain for current NPL reduction needs.

The Chinese NPL market today

The official NPL ratio in China is likely to continue increasing from a low base, due to both macro and regulatory factors (as some exposures get reclassified as NPLs). The largest banks have manageable NPL ratios, but the problem is likely more acute in specific provinces and smaller banks, and could become a broader issue in a downturn.

NPL securitisation, so far seldom used where most needed, could contribute to resolving Chinese NPL issues. It should follow best practice, i.e. by securitising a diversified pool of loans, with banks retaining some residual exposure, and by mandating the restructuring of ailing, yet viable firms (Daniel et al., 2016).

The Chinese secondary NPL market has the potential to be the largest in the world, with an estimated RMB 9.7 trillion of NPLs as of June 2018 (USD 1.4 trillion). In order to support the bank balance sheet clean-up, such a market needs buyers. Yet, it remains fairly closed to private investors. The evolution of the market reflects a very gradual opening to foreign capital in NPL purchases, under the government’s terms. In the near term, the role of state-controlled entities is therefore likely to remain dominant.

The future role of AMCs

The 2017 IMF Financial system stability assessment for China noted that “the current set-up, with a dominant role for the four nationwide AMCs, facilitates disposal of problem bank assets”. However, the future role of the AMCs will depend on the magnitude of the NPL clean-up. Barring a more severe macroeconomic downturn, the large banks are expected to manage their NPLs through a combination of in-house workouts, sales and internal AMCs that some of them have set up. Small and medium-sized banks will depend more on NPL sales.

Notwithstanding their transformation, the big four AMCs have become a permanent feature of the Chinese financial system, which opens up the possibility of a return to their original purpose, as per the authorities’ recent guidance. They now operate on more market-based terms than before, but are still subject to government influence, which could lead to further involvement in banking sector interventions. Regional AMCs, which reportedly accounted for almost half of all NPL purchases in 2017 and 2018, can also play a role. The contribution of the AMCs to systemic NPL resolution will be a function of their purchasing power in proportion to the size of the overall bad debt stock, as well as the Chinese State preference for centralised solutions going forward.