Post n° 346. This blog post analyses the gender pay gap in France, showing how differences in working hours, job roles and employer practices have shaped earnings between 2002 and 2019. The gap has narrowed because women are increasingly sorting into better-paid sectors and occupations. The within-firm gap has decreased only slightly and remains significant.

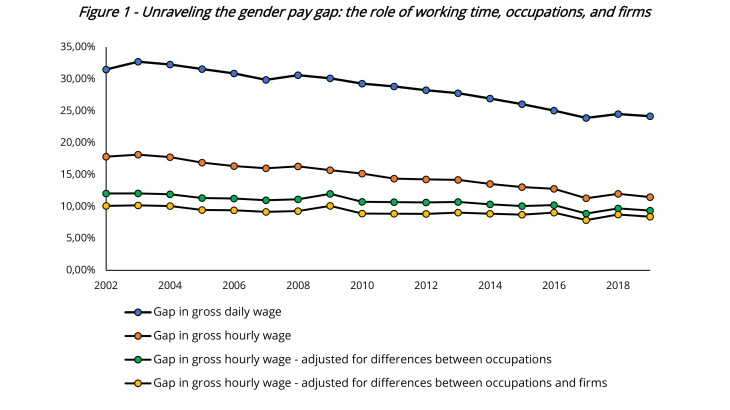

Note: The gross daily wage and the gross hourly wage correspond to the annual gross wage divided by the number of days and hours worked in the year, respectively

Understanding what drives the gender wage gap has been the subject of considerable economic research for decades. When differences in qualifications are controlled for, the gap tends to widen further, as women today tend to have better qualifications than men do. While this reflects the fact that women are more likely to work fewer hours and be employed in lower-paid occupations and firms, in many countries most of the gap is concentrated within firms (OECD, 2021).

Palladino, Roulet and Stabile (2023) examine how the gender pay gap and its worker- and firm-specific components have evolved over time in France. They use a new comprehensive employer-employee dataset (Babet et al., 2023) derived from the “Base tous salaries” register to examine the gender gap in gross earnings in the private sector between 2002 and 2019. This dataset provides a comprehensive perspective, covering not only the earnings associated with each job, but details of the number of days worked, the number of hours worked, the type of occupation and the employer.

The role of working time and occupation

All of this information is used initially to construct a measure of daily earnings, corresponding to the ratio of annual gross earnings to the number of days worked. The gender gap in daily earnings fell from over 30% to less than 25% between 2002 and 2019. There is a 'volume' component that can be explained by analyzing the number of hours worked. Figure 1 shows that differences in daily workload, largely explained by part-time work, contribute significantly to the gross differences in average earnings per day worked, but their weight has not changed significantly over time: the gender gap in terms of hourly earnings fell from 18% to 11.5% between 2002 and 2019.

After adjusting for differences in working hours, it is possible to assess the impact of occupational segregation, corresponding to the difference between the orange and green-marker lines in Figure 1. Over the years, there has been a convergence: women are relatively more likely to be employed in higher-paid occupations than in the past, a fact already well established in the literature. Occupations accounted for one-third of the gender gap in hourly earnings at the beginning of the period, but only one-fifth by 2019.

The role of firms

Even after accounting for differences in hours worked and occupational segregation, the gender gap in earnings remains substantial (9.3 percent in 2019). A more recent strand of research has adapted the Abowd, Kramarz, and Margolis (1999) model to measure the role of firms in explaining this residual gap (see, for example, Card, Cardoso, and Kline, 2016). Using this framework, the role of firms can be broken out into a between- and a within-firm component. The former measures whether women work in lower-paying firms or industries compared to men with similar tasks and responsibilities. The second component looks at whether men and women are paid differently within the same firm, either because of different tasks and responsibilities within the same occupation, or because of differences in wage bargaining and/or unfair pay practices, i.e. discrimination (OECD, 2021).

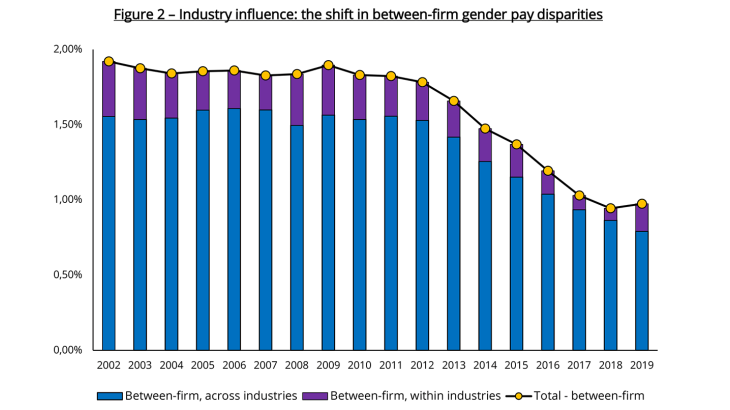

The difference between the green and yellow marker lines in Figure 1 captures the between-firm component, which can be further broken down into a between- and within-industry component as shown in Figure 2. The total between-firm component, already modest at the beginning of the period, declines over time, starting around 2014 and continuing through the end of the period. Most, i.e. 75% of the decline in the between component over the period of analysis is explained by a decline in the between-industry channel. In other words, women are increasingly sorting into industries with higher-wage firms, rather than gaining access to higher-paying firms within industries.

Note: The total between-firm gap is the pay gap attributable to women working in lower-paying firms or industries compared to men.

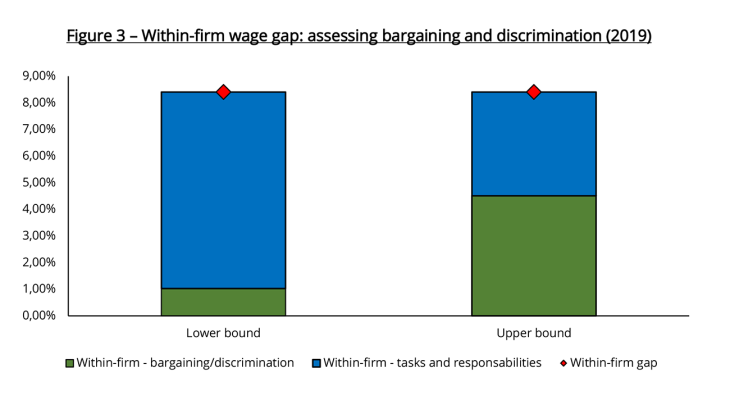

Finally, we are left with the assessment of the within-firm gap, which is significant both at the beginning and at the end of the period of analysis (around 10 percent in 2002 and 8 percent in 2019). Assessing the change over time of its two components – i.e. differences in tasks and responsibilities within a given occupation, and bargaining/discrimination channels - relies on certain assumptions concerning the underlying econometric model and cannot be fully evaluated in this context (Palladino, Roulet and Stabile, 2023). Figure 3 shows credible lower and upper bounds for the bargaining/discrimination component for the most recent year available. We see that this component, which is the closest we can come to identifying differences in pay for work of equivalent value, ranges between 1 and 4 percent, accounting for between 10 and 40 percent of the total hourly wage gap in France in 2019.

Note: The total within-firm gap is the pay gap attributable to men and women being paid differently within the same firm.

The role of policies

In 2019, France introduced a significant pay transparency reform aimed at addressing within-firm gender wage gaps. Under this reform, companies with 50 or more employees are required to conduct regular equal pay audits and publicly report information on the gender pay gap (known as the Professional Equality Index (or “Index de l’Égalité Professionnelle entre les Femmes et les Hommes”). Several other countries have also implemented similar measures.

While these actions play an important role in making gender pay gaps more visible, this blog post proves that their implementation can be complex. Determining whether gender pay differences within a specific firm are due to systematic disparities in tasks and responsibilities or to unequal pay for work of equivalent value is challenging.

This discussion highlights the fact that although policies targeting pay differentials within firms are indeed valuable, they are unlikely to be sufficient on their own. To achieve meaningful change, it is essential to address the underlying reasons for gender differences in the demand for flexible work arrangements and in mobility across occupations, tasks, industries, and firms.

Download the PDF version of the publication

Updated on the 25th of July 2024