- Home

- Governor's speeches

- The competitiveness of the banking secto...

The competitiveness of the banking sector: a few insights into a major challenge for France and Europe

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on the 25th of November 2025

ACPR Conference

Paris, 25 November 2025

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am delighted to welcome you to this year’s ACPR Conference focusing on the resilience of the financial sector and, on this fifteenth anniversary, the ACPR itself is a fine example of resilience. I would like to kick off this morning with an essential component, namely the competitiveness of the French and European banking sector. Granted, from a legal perspective, this is not part of the ACPR's mandate, but there is no need for any change in legislation for this subject to be of long-standing importance for us too: it relates to the strength and innovative capacity of our financial system. It lies at the heart of our economic sovereignty and needs to be treated seriously as well as with clarity. First, let us consider the facts: French banks are financially sound aside from a temporary lag in profitability due to the predominance of fixed-rate loans, however the real challenge is at the transatlantic level (I). Next, let us analyse certain explanations that are often put forward – regulation and payments – with discernment (II). Lastly, let us broaden the outlook around two decisive drivers, i.e. the size of financial institutions and public support (III).

I. The facts: structural soundness and a transatlantic challenge

1.1 A temporary lag, reflecting a protective fixed-rate model

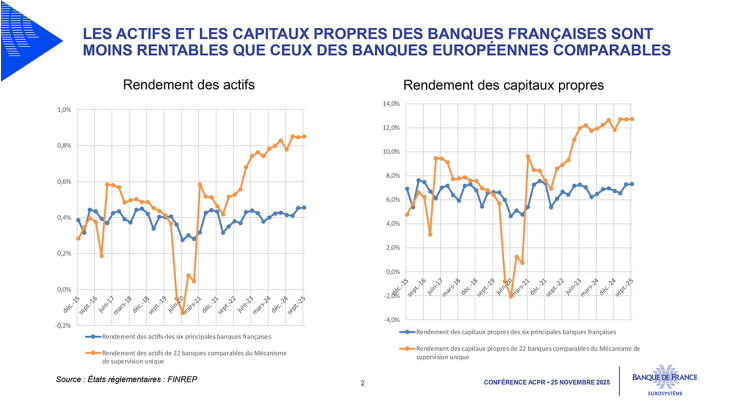

Let us begin with a lucid but nuanced overview. Yes, French banks are currently lagging behind their European counterparts in terms of their profitability ratios. Since interest rates began to rise in 2022, a difference has appeared in the asset yields between French and European banks.

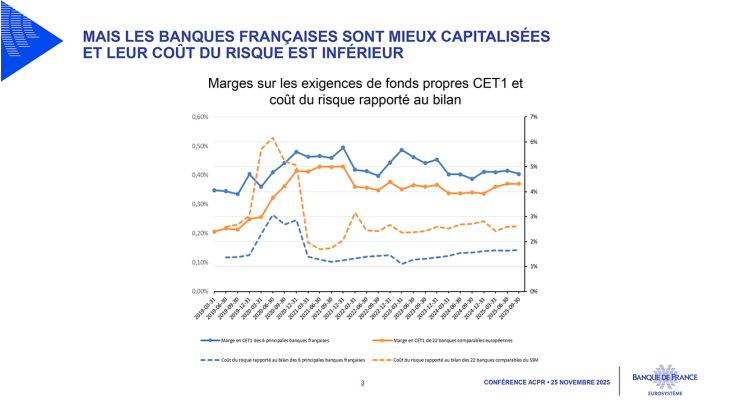

Return on equity is also lower, averaging 6.7% over the same period for French banks, compared with 11.2% for comparable SSM banks. This lag is real, but it should be temporary. It is mainly due to the predominance of fixed-rate loans, limiting the growth in interest income when interest rates rise (inertia of previously low rates). Conversely, during periods of extremely low rates, French banks' interest income, although lower, declined less sharply than that of comparable Spanish or Italian banks. This French model has a short-term cost for institutions, but it protects borrowers and limits the cost of risk.

However, we need to look at the bigger picture. French banks remain among Europe’s strongest, with high average capitalisation levels – higher than their European counterparts – rigorous risk management, and a proven ability to adapt.

They are also among the most diversified, with the share of income related to commissions and market activities nearly twice as high as their euro area peers, and universal business models that afford them valuable resilience.

1.2 The real challenge: bridging the transatlantic gap

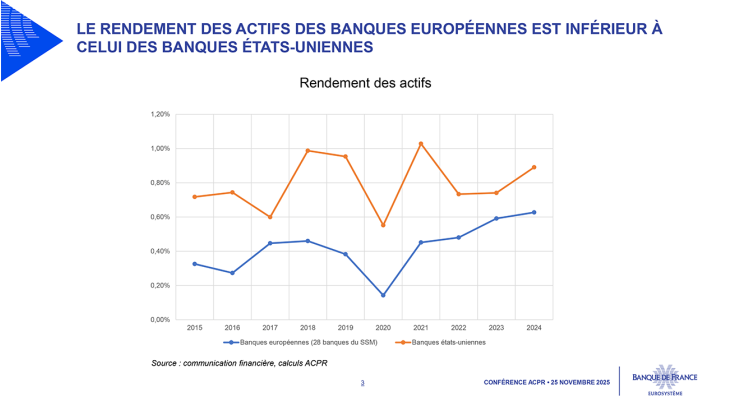

The gap in competitiveness is most pronounced – and most worrying – between European and American banks.

European banks as a whole struggle to compete with large American institutions, which benefit from a dynamic domestic market with high margins, particularly in investment banking. The figures speak for themselves: US investment banking revenues are around three times higher than those of European banks.

II. Examining with discernment two traditional explanations put forward by the sector: regulation and payments

2.1 Regulation: simplifying without deregulating

Financial regulation is frequently mentioned to explain the difference in competitiveness between European and American banks. Yes, the European regulatory framework is dense – sometimes overly – but no, the solution cannot lie in deregulation. Financial stability is a common good that aims to prevent the immeasurable costs of banking and financial crises. Let’s not be too quick to forget 2008, especially when financial stability appears to be fragile, across equity, cryptocurrencies, and private credit markets. It is not a question of choosing between robustness and efficiency, but of reconciling the two. We need to aim for ambitious simplification: there is room for improvement in Europe for making things less complex without making them less secure. A year ago, right here, I put forward proposals to this effect.i

In this same spirit, we now need to review the simplification initiative launched at European level. Progress has been made in several areas, especially in supervision and reporting. The SSM has taken the first tangible steps in relation to the Next Level Supervision initiative: greater efficiency and focus on risk through digitalisation, standardised and faster processes, and fewer unnecessary charges. In early October, the European Banking Authority proposed 21 simplification measures to ease the reporting burden, which will be implemented in the very near future for the entities within its remit. These are a step in the right direction and we support their expansion and their effective rapid implementation.

On regulation itself, we have participated in the ECB's High-Level Task Force, and in December it will submit its proposals to the Commission to contribute to the overall “review” next year. There are ways to simplify without deregulating, but this cannot involve imposing additional requirements on European banks: the results of the latest very stringent stress tests published on 1 August 2025 show that these banks are sufficiently capitalised, both collectively and individually. I am specifically referring to the removal of thresholds that trigger the maximum distributable amount related to MREL and leverage frameworks. I am also referring to the streamlining of the resolution framework by achieving a better fit with the TLAC international standard. We also need to rethink certain overly complex aspects of European regulation, such as the systemic risk buffer (SyRB), which does not exist anywhere else. There is scope for merging or even eliminating certain buffers.

Let's face it: there is also room for simplification at the national level. To cite just one example, the Banque de France and the ACPR remain more committed than any other institution to the fight against climate change, however, the reporting requirements in place for four years under Article 29 of the Energy and Climate Act ii (LEC29) specific to France are of very little use and fit very poorly with the related European provisions. Moreover, AI could help us to “streamline” a lot of existing legislation in the future.

2.2 Digital euro and tokenisation: we must not fight the wrong battle

A second factor that is sometimes mentioned is payments, particularly with regards to digital currencies. And here again, erroneous debates must be avoided. The issue is not public versus private. It is rather Europe versus the United States. It is transatlantic, not intra-European.

En effet, nous sommes confrontés à un double défi de souveraineté :

• Regarding payments: every day we use the services provided by two major US “schemes” that account for 69% of all card transactions in the euro area (in the second half of 2024); although, fortunately, this rate is less than 30% in France thanks to the strength of the GIE Cartes Bancaires infrastructure.

• Regarding currency: the US administration is promoting the surge in stablecoins, 99% of which are backed by the US dollar, raising the risk of “privatisation” and “dollarisation” of our currency.iii

Firstly, we actively and urgently support the development of a wholesale central bank digital currency, which will allow banks to benefit from settlement in a central bank money in a tokenised environment. It represents a decisive step forward in the modernisation of financial infrastructures and in European monetary sovereignty. And there is general consensus here, but it must go hand-in-hand with the development of a tokenised private currency, in euro, which could take the form of tokenised bank deposits or euro-based stablecoins issued by banks. Europe could have both, but it would be a terrible mistake to have neither.

As for retail payments, the digital euro is one of the keys to the solution. Let us move beyond the sometimes surprising excess of emotion and passion surrounding this issue. The Eurosystem is designing the digital euro in a logic of “public-private partnership” with banks, which will play a central role in its distribution. It will not threaten European private payment solutions, but rather it will be a catalyst: we are fully behind Wero, which recently joined forces with other national mobile payment solutions (such as Bizum in Spain) within the EuroPA consortium. The digital euro will assist these solutions by facilitating the development of open and harmonised acceptance standards throughout the euro area. This partnership will thus strengthen the competitiveness of European banks; on the contrary, if we do not develop it, European dependence on US technology and financial giants will deepen.

III. Broadening the outlook around two key drivers – size and public support

3.1 Size: a structural handicap

European banks are too fragmented; too small on a global scale. 45% of US bank assets are owned by the five largest banks, whereas in Europe, this ratio is only about 33%. Moreover, US banking group subsidiaries play a significant and increasing role in market activities and investment banking: they account for over 55% of investment banking commissions in Europe.

The size of European banks limits their ability to invest heavily in the technologies of tomorrow – artificial intelligence, quantum computing and cybersecurity – as these investments entail high fixed costs, which larger institutions can better absorb.

We must therefore remove the political and regulatory obstacles that hinder the creation of cross-border European champions – by reinvigorating the Banking Union. The Savings and Investment Union – it has not been stressed often enough – draws together the Banking Union and the Capital Markets Union, uniting them rather than pitting them against each other. We have more than a decade of effective SSM supervision behind us; it is high time that we learn from this experience so that liquidity and capital can flow more freely within banking groups and their subsidiaries in the Banking Union. We must revisit the criteria, which today are too strict, for granting waivers allowing for the consolidated management of liquidity requirements within European groups. And we must go further by removing Pillar 2 requirements for subsidiaries within the SSM and by introducing the possibility of waivers that favour the management of capital that is itself consolidated in Europe.

As for the deposit guarantee, rather than always chasing the dream of a complete system, of a “fully-fledged EDIS”, a decisive step would be to create a European liquidity support scheme, between national guarantee schemes, which would act as a safety net. I have already suggested it, as has my German colleague, Joachim Nagel.iv

3.2 The need for a public strategy

The banking and financial sector is a strategic strength for France and for Europe. And for France in Europe, since our country possesses the largest financial industry in Europe. It cannot be solely perceived as a source of risk or tax revenues. It must be recognised as a vector of sovereignty and competitiveness. This is certainly true in retail banking – which often attracts more political attention – and is no less true in investment banking, which is crucial both for financing our three major transformations – digital technology and AI, decarbonised energy, and defence – and for boosting companies' equity capital in order to close our innovation gap.

The United States grasped this a long time ago. Its support for its financial institutions is strategic, even if excessive deregulation would be dangerous. And this is a lesson we have to learn. Over 25 years ago, Europe won its monetary sovereignty with the tremendous success of the euro. Today, faced with the current US administration’s offensive, the Draghiv and Lettavi reports set out a clear path for a new “leap in sovereignty”. But there will be no economic sovereignty without financial sovereignty. And that means consistent tax policies, moderating regulatory temptations, including at the national level, and a shared European ambition.

**

The competitiveness of the French and European banking sector is a major strategic issue. It is not simply a matter of ratios or rankings. It affects our ability to finance our economy, support transitions and defend our model. We have the means: robust banks, committed regulators, a common and well-recognised currency. But we must remove the obstacles: complex regulations, market fragmentation, a lack of strategic vision. This is the ambition that we are committed to, working together, for a stronger European banking sector. Thank you.

i Villeroy de Galhau (F.) (2024), “Towards a realistic simplification: untying some of the knots in European banking regulations”, speech to the ACPR conference, 27 November.

ii Loi n°2019-1147 du 8 novembre 2019 relative à l’énergie et au climat

iii Villeroy de Galhau (F.) (2025), “L’Europe a les moyens de la bonne réponse stratégique à la révolution de la monnaie”, interview with the journal Le Grand Continent, 25 September.

iv Villeroy de Galhau (F.) (2025), Financial services: The European mysterious gap, speech at the Bruegel Annual Meetings, Brussels, 4 September.

v Draghi (M.) (2024), The future of European competitiveness, September.

vi Letta (E.) (2024), Much more than a market, April.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 25th of November 2025