Central banks monitor inflation using a variety of indicators

The price stability objective of central banks, and in particular the ECB, means that they must be able to assess not only current and future inflation developments but also the perception of inflation of economic agents. As regards current inflation, the consumer price indices published by national statistical institutes such as INSEE are closely analysed, be it for headline inflation, its components or measures excluding the most volatile items. Projections are also conducted to assess the inflationary or deflationary risks to the economy.

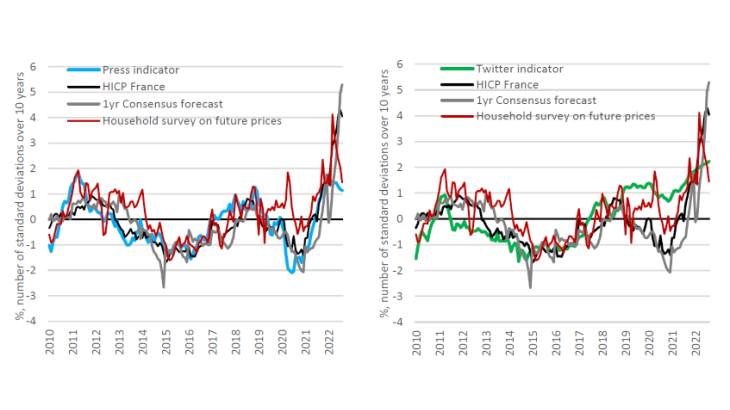

Maintaining price stability also requires that the inflation expectations of economic agents, households or companies, remain anchored around the inflation target set by the central bank. To measure inflation expectations, several indicators are used: i) expectations from financial markets, measured using inflation-linked bonds or inflation derivatives, ii) expectations of forecasters based on surveys (e.g. the Consensus Forecast or the Survey of Professional Forecasters), iii) expectations of companies (e.g. in France, the new survey of business leaders conducted by the Banque de France) and iv) expectations of households from surveys for example the European Commission's consumer survey or the European Central Bank's Consumer Expectations Survey (CES). The analysis in this post focuses on the way inflation is perceived through certain forms of media and the short-term expectations that can be derived from this.

Text mining of alternative data to complement traditional sources

The media disseminates a wealth of data that may reflect the inflation perceptions and expectations of households and businesses. This includes traditional media such as television, radio and print media or social networks. In the case of the press and social networks, processing this volume of data requires the use of data science techniques that analyse qualitative textual data and transform them into quantitative figures that can be used by economists in the form of indicators.

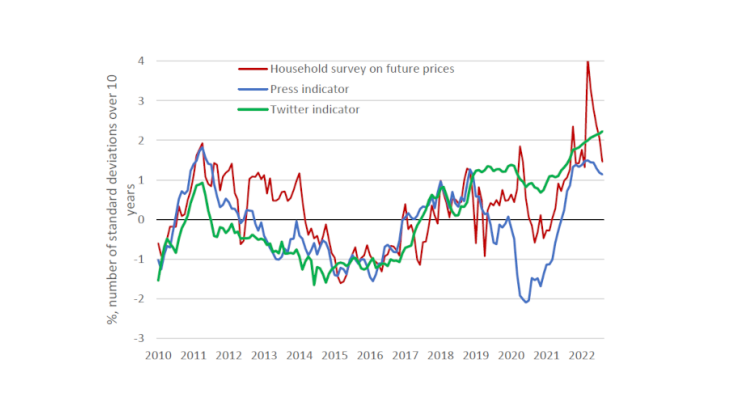

A recent work in this area, carried out at the Banque de France on French data, collects and analyses more than one million articles from the written press since 2003 (source Factiva) as well as around four million tweets since 2012 (source Twitter) to construct indicators of perceived inflation (in the spirit of the work of Angelico et al. 2022 for Italy).

The method is based on the selection of articles and tweets using keywords (related to the semantic field of "inflation" or "prices"). Filtering and classification algorithms are used to select only those that actually deal with inflation and not other subjects (e.g. literary 'prizes') and to derive the direction of inflation/prices that may be mentioned in the text (rising, falling or stable). Extensions were also explored, to exclude articles that might reflect the views of central banks themselves, and focus more on households.

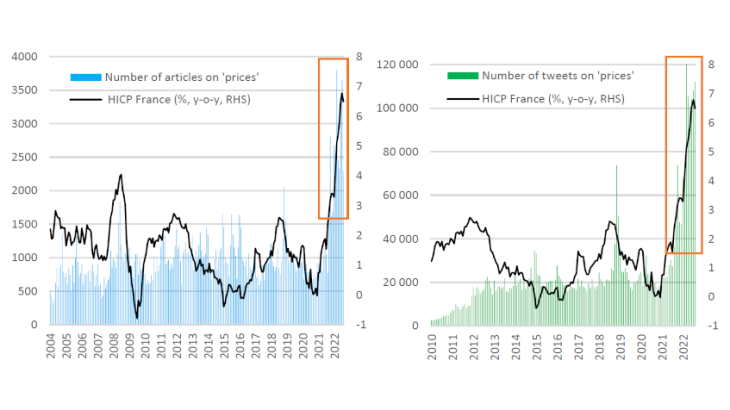

Chart 2 shows the number of press articles and tweets resulting from the first stage of filtering and that can be interpreted as an indicator of attention to inflation in the media (traditional and social networks). At first sight, attention to inflation appears to increase during episodes of strong inflation or deflation - when inflation deviates from its mean value - and in particular in the recent period since mid-2021 (see rectangles in Chart 2).