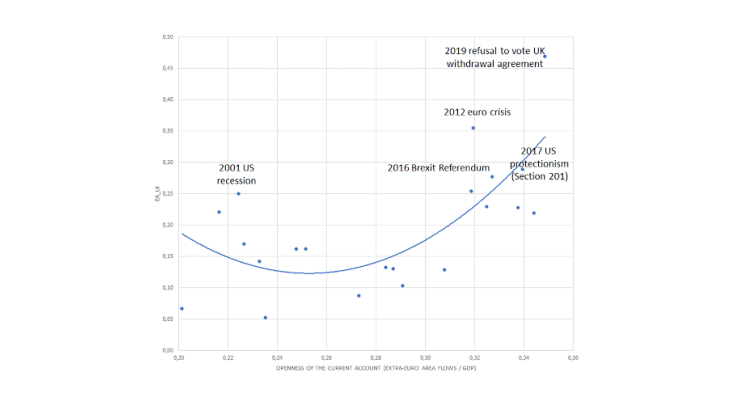

Note: y-axis: GDP-weighted average of the quarterly euro area uncertainty indices (EAUI). X-axis: half-sum of euro area current account payments and receipts relative to its GDP (CHELEM). Uncertainty data are missing for Cyprus, Estonia, Luxembourg and Malta.

A large amount of uncertainty in a highly globalised economy

Why did Christine Lagarde declare in 2020 "There is no doubt that the economic situation we face today is characterised by profound uncertainty. Looking into the future has rarely been harder"?

Why have economic policy makers, in particular monetary authorities, become more attentive to uncertainty? Because it has increased sharply, in parallel with economies’ growing interconnection as a result of globalisation. But the relationship between the perception of uncertainty, whose shocks spill over to the real economy, and globalisation is complex. Certain episodes of high uncertainty (such as the US recession following the September 11 attacks) occurred at a time when economies were less globalised than today, with limited global impacts. The period of sustained growth, from 2001 to 2008, was marked, on the other hand, by an acceleration of globalisation in a world that had become less uncertain. Ultimately, it is the return of strong uncertainty in a now highly globalised world that gives cause for concern. The nature of globalisation has also changed since the great financial crisis, with trade in goods no longer growing at a faster pace than world GDP, even if this trend is less marked in the euro area. Services and income, especially financial income, are now posting strong growth, creating an additional potential source of uncertainty. Whatever the indicator, the level of globalisation remains high at the end of the period in the euro area.

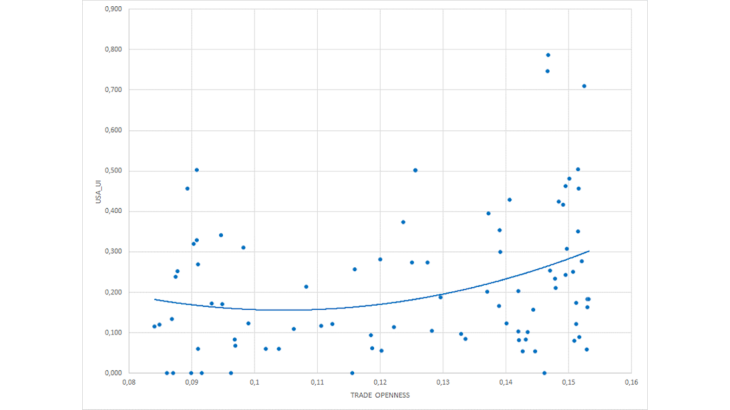

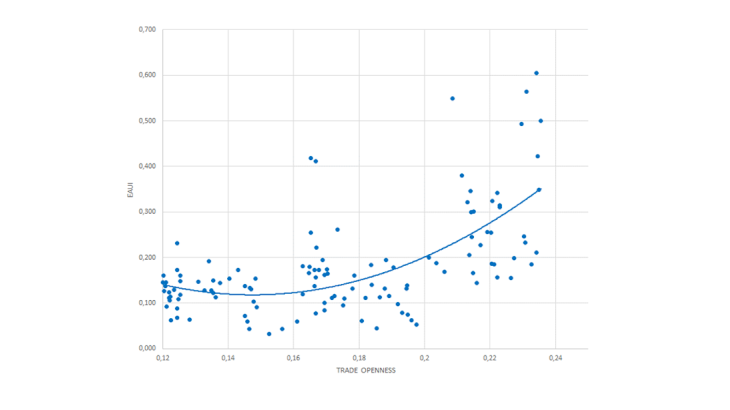

This relationship between globalisation and uncertainty becomes clearly apparent if we relate the various indicators of the euro area’s integration into the global economy to the indicator of Ahir et al. (2018), which is reconstructed in this post for the euro area countries alone. This indicator increases with the frequency of appearance of the word "uncertainty" in the country reports of the Economist Intelligence Unit for the major euro area countries (EAUI in Charts 1 and 2). Peaks of uncertainty appear during the following episodes: the US recession (already mentioned), the sovereign debt crisis in the euro area, the vote in favour of Brexit, the United States’ shift towards protectionism, the US presidential campaign, and finally the refusal to vote the UK's withdrawal agreement.

While the global financial crisis has illustrated how a financial shock can be transmitted globally and lead to a deep and lasting recession, Brexit and the 2011-2013 euro crisis are the two events that are associated with increased uncertainty in the EU. In Chart 1 this uncertainty is related to the degree of globalisation of the euro area at each date, taking into account trade in goods and services and the euro area's international income as a proportion of its GDP, i.e. the current account. This relationship is still visible, albeit attenuated, if we limit ourselves to the globalisation of trade in goods and services. This is shown in Chart 2, this time for the United States, for the period again starting with the creation of the euro, but including the first quarter of 2020. Chart 3 extends the period covered to the whole of the 1990s, for the euro area, and also includes the outbreak of the Covid-19 epidemic in the first quarter of 2020 (Berthou et al., 2020). The succession of these shocks gives rise to a growing sense of global unpredictability, adding to the effect of stronger (and more complex) interconnections between countries at the global level (Ludvigson et al., forthcoming).