- Home

- Deputy governors' speeches

- Central bank accounts: the corollary of ...

Central bank accounts: the corollary of success

Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Second Deputy Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 31st of March 2025

Tribune By Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Second deputy-governor of Banque de France.

One after another, the euro area and non-euro area central banks have published their financial statements for 2024 (see Table 1). As for the Banque de France, it held its annual press conference on 19 March 2025, and its 2024 Annual Report is available on its website. As expected, profit/loss before tax showed a significant loss of EUR 17.4 billion as a result of a scissor effect between low-yielding assets, inherited from a period of very low interest rates prior to 2022, and liabilities mainly remunerated at the ECB deposit facility rate (3.73% on average in 2024).

Table 1. Results of selected central banks for 2024

| ECB | Germany | France | Australia* | Canada** | Netherlands | |

| Profit/loss before allocation to provisions | -7,9 | -19,8 | -17,8 | -3,5 | -1,15 | -3,2 |

| Profit/loss after allocation to provisions | -7,9 | -19,2 | -7,7 | -3,5 | -1,15 | 0 |

| Accumulated losses carried forward | -9,2 | -19,2 | -7,7 | -16 | -5,2 | 0 |

Source: Annual reports.

Notes: * June 2023 to June 2024; ** three first quarters of 2024.

However, these figures should not worry us. In fact, they should be seen as a corollary of our successful fight against inflation (see also my 2024 opinion piece on the subject).

No cause for concern

Over the 2015-22 period, the Banque de France reported accumulated profit before tax of EUR 45.8 billion. It paid EUR 16.3 billion in corporation tax and EUR 15.5 billion in dividends to its only shareholder, the French state (see the 2023 Annual Report, p. 95). The remainder of the profits was transferred to various reserve accounts, including the “Fund for General Risks”, which meant that the entire loss before tax and extraordinary items for 2023 of EUR 12.4 billion and a substantial part of that for 2024 could be absorbed, leaving a net loss for 2024 of -EUR 7.7 billion.

If we think in terms of stocks (the balance sheet) rather than flows (the profit and loss), paradoxically we see an increase in net worth from EUR 169.7 billion at year-end 2023 to EUR 202.7 billion at the end of 2024. This is due to unrealised capital gains of EUR 52 billion, in large part due to the rise in the price of gold (2024 Annual Report, p. 119). As these capital gains are unrealised, they have no impact on profit or loss. Nonetheless, they show that the Banque de France’s balance sheet has not deteriorated, despite the net losses allocated to equity.

Furthermore, the scissor effect described above should gradually disappear in the years to come, for two reasons. First, the balance sheet is contracting. It reduced from EUR 1,597.0 billion at year-end 2023 to EUR 1,515.7 billion at year-end 2024, and will continue to contract by EUR 7.7 billion per month in 2025, in line with the policy of normalisation following the exceptional measures taken between 2015 and 2021. Thus, the balance sheet is shedding its low-yielding securities. Second, the interest rate paid on bank reserves has fallen. It is already down to just 2.5% (since 12 March 2025), compared with 4% in the first half of 2024. Consequently, profit should recover mechanically from 2025.

Lastly, as the Banque de France's only shareholder is the French state, we can consider the consolidated balance sheet of the two entities. This does not include the French government bonds held by the central bank, which offset each other as an asset for one and a liability for the other (see Table 2). In passing, it is worth noting the inanity of the debate on a hypothetical “cancellation” of the public debt held by the central bank (see Bénassy-Quéré, 2020).

The public debt securities held by other central banks and by the private sector, however, are still included in liabilities. At the same maturity, their rate of return would be the same as that of securities held by the central bank – a return lowered by past policies. Nevertheless, the maturity of the aggregate liabilities has shortened, making the consolidated balance sheet more sensitive to changes in key interest rates.

Table 2. Simplified consolidated public sector balance sheet

| Assets | Liabilities |

|

Private debt securities held by the central bank

|

Public debt securities held by the private sector Commercial bank reserves Currency Other liabilities Net worth |

Source: Adapted from Cecchetti and Hilscher (2024).

Looking at the consolidated balance sheet, we could wrongly conclude that public debt is of no importance as long as it is held in the balance sheet of the central bank. But if the central bank pledged to keep these securities, in reality it would find it impossible to reduce the quantity of money in circulation in the event of a surge in inflation. And yet the economic value of a sovereign state is a direct reflection of the quality of its public policies: markets continue to lend to the French state primarily because of its ability to raise taxes in the years to come, and therefore to service its debt. The outlook for growth and price stability are key.

The corollary of success

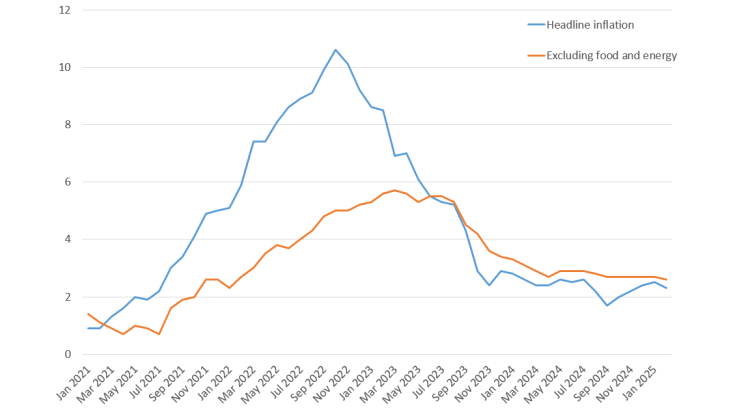

When the Eurosystem Governing Council sharply raised its key interest rates to fight inflation, it was fully aware that it would result in accounting losses, as the interest received on assets could not adjust at the same pace as the interest paid on liabilities. In other words, it knew that the interest rate risk accumulated between 2015 and 2021 through the purchase of long-term bonds would materialise if it raised short-term interest rates, which determine the return on commercial banks’ reserves. The Governing Council decided to raise its rates because its mandate is not profit maximisation, but price stability. And sure enough, inflation quickly returned to a level close to 2% (see chart).

Chart: Harmonised index of consumer prices inflation, euro area, year on year variation (%)

What would have happened if the Governing Council had set its monetary policy to avoid temporary losses? Based on the ECB's macroeconomic forecasts as of December 2023, Gebauer, Pool and Schumacher (2024) show that inflation would have been substantially higher. Renouncing its price stability mandate in such a way could also have resulted in a de-anchoring of inflation expectations, which would have pushed inflation up by several additional percentage points (see Dupraz and Marx, 2025).

Along the same lines, Adrian et al.(2024) use a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model to show that in times of recession and interest rate constraints (zero lower bound), a policy of quantitative easing has a three-fold effect: stabilising activity and prices; benefiting fiscal revenues; and (temporarily) increasing central bank profit. These effects are only partially diluted when policy rates rise, generating losses in the central bank's accounts but still contributing to macroeconomic stabilisation. However, the authors stress that these conclusions only hold true if quantitative easing is used during a “liquidity trap” – when it is impossible to act by lowering interest rates.

To sum up, the losses reported by the Banque de France in 2023 and 2024 are cyclical in nature. They occur after years of profit that allowed the Banque de France to build up its reserves and thus absorb the losses. And the losses will not persist, because the mismatch between interest earned and paid on assets and liabilities will narrow mechanically from 2025 onwards. Finally, an annual loss of around half a percentage point of GDP is a small price to pay given the crucial importance of maintaining well-anchored inflation expectations and successfully bringing inflation back to its anchor. At a time when fiscal leeway for macroeconomic stabilisation is a concern, given current levels of debt, we should be pleased to have a powerful monetary instrument to manage episodes of inflation.

Updated on the 31st of March 2025