Post No. 394. The share of women among French business leaders had risen to 25% in 2023. The under-representation of women is due in particular to family constraints, which continue to weigh more heavily on their professional careers.

Chart 1 Percentage of women among business leaders

Female representation within the ranks of business leaders is progressing but a gap persists

In 2023, women accounted for over half the French population (52%) and almost half the labour force (49%), but only 25% of business leaders, defined here as corporate officers (e.g. managing director of a limited liability company or CEO of a public limited company). This figure falls to 17% in the largest corporate structures (i.e., in intermediate-sized enterprises (ISEs), and larger enterprises (LEs), compared with 26% in microenterprises and 19% in other SMEs (see Chart 1, and Berardi and Bureau, 2025 (in french), for a more detailed presentation of the elements summarised in this blog post).

The number of female business leaders has increased over the last twenty years, particularly in ISEs and LEs, where women represented only around 5% at the turn of the 21st century. But progress remains relatively slow and, at this rate, achieving gender parity will still take many years.

The gender imbalance is even more marked if we focus on large listed groups. Women only headed up 6.25% of CAC 40 companies in 2023 (compared with 3.75% in 2022, and 2.5% in 2021). In recent years however, the French legislator has sought to encourage the appointment of more women to the governance bodies of large companies. The Copé-Zimmermann Act of 2011 introduced female quotas for the boards of directors and supervisory boards of ISEs-LEs (40% since 2017). The Rixain Act of 2021 introduced female quotas for the executive committees (which assist the CEO and include a group's key senior managers) of companies with more than 1,000 employees (30% by 2026, 40% by 2029). In recent years, these laws have clearly boosted the proportion of women on boards of directors and supervisory boards (up from 29% to 46% in less than ten years for SBF 120 companies), and on executive committees (up from 12% to 29%).

Consequently, France leads OECD countries in terms of the proportion of women on the boards of directors and supervisory boards of listed groups (46% in 2022, compared with 43% in Italy, 35% in Germany, 32% in the United States and 15% in Japan, for example; see OECD, 2023a). It also ranks in the top third of OECD countries in terms of the proportion of women managers more generally (i.e., not just executive committees, and for both listed and unlisted companies): 38% in 2021, compared with 41% in the United States, 29% in Germany and Italy, and 13% in Japan (see OECD, 2023b). While we do not have sufficiently reliable data to make the same comparison for business leaders alone, there is every reason to believe that the paucity of female business leaders highlighted above is by no means a French exception.

The presence of female managers varies greatly from one sector of activity to another

The least feminised sectors are construction and transport, with 4% and 10% respectively of companies run predominantly by women (see Chart 2). By way of contrast, the sectors with the highest proportion of women are education, health and social work (35%) and “other services” (46%). The latter corresponds to French NAF sub-sectors “R. Arts, entertainment and recreation” and “S. Other service activities”.

At a more detailed sectoral level (i.e., 4-digit NAF codes), the results become especially gendered: the sub-sectors with the highest proportion of women are jewellery, childcare, hairdressing, beauty care, perfumes, clothing and flowers. Conversely, the sub-sectors with the lowest proportion of women are electronics, electricity, plumbing, construction and machinery.

Chart 2 Percentage of companies run by women in 2023 - by sector of activity

Source: Banque de France, FIBEN database.

Family constraints continue to weigh more heavily on women's working lives

Why are there so few female business leaders? The work of Claudia Goldin, winner of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Economics, shows that inequalities in the labour market - in terms of participation and wages - primarily reflect inequalities within households in terms of the distribution of the work of looking after children and fragile family members. In this context, within (heterosexual) couples, women are more likely to turn to “flexible jobs” that pay less but leave more time to look after their families. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to invest in what Claudia Goldin calls “greedy jobs”, in other words, jobs that require long working hours, where pay (per hour worked) increases with the number of hours worked, and which demand a high level of availability (with possible demands on evenings, weekends, holidays, etc.). Business leader positions, which often require a major personal investment, are similar to “greedy jobs” - except that, in practice, high pay is by no means systematic (particularly in SMEs). Aside from the question of children and dependent relatives, INSEE (2022) indicates that gender inequalities are only slowly being reduced in the area of domestic work (housework, preparation of meals, food shopping).

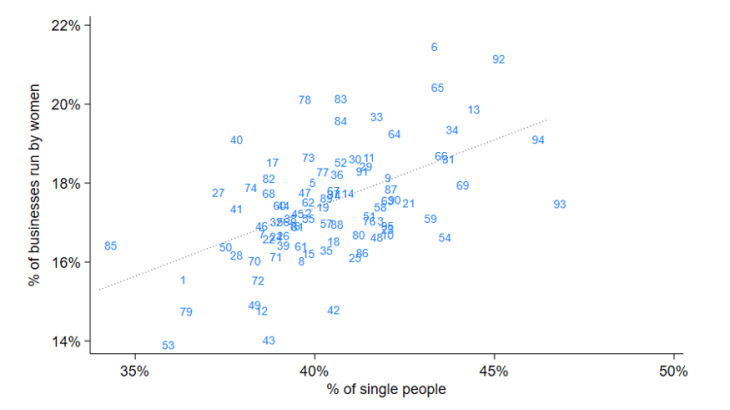

In a similar vein, DGE-DGCS (2019) indicates that family constraints are identified as the main brake on women setting up businesses and that as a consequence, 40% of female entrepreneurs are single compared with 21% of men. Chart 3 shows a fairly strong correlation between the proportion of businesses run by women and the composition of households in the region (even when reasoning at a fairly aggregated level - in this case at departmental level). These correlations are presented for illustrative purposes and are not a substitute for a causal estimate, but we can verify that they are robust and cannot be explained, for example, by factors such as differences in inter-regional sectoral composition, business size or urbanisation rates.

Chart 3. Correlation - at departmental level - between % of single and % of women business leaders

Source: Banque de France, FIBEN (company data) and INSEE database (data on household structure).

Under-representation of female business leaders: a brake on the economy?

Gender inequality in access to business leader positions raises questions about equity insofar as the opportunities available to men and women are not the same, but it also raises questions of economic efficiency. Indeed, if we assume that the distribution of talent is identical within the female and male population (i.e., the same proportion of talented individuals among men and women), then the existence of barriers for women is likely to deprive the French economy of talented female business leaders, while at the same time, promoting some less competent male business leaders to these function (because more competent women have not had the opportunity to become business leaders, to compete with and ultimately drive them out of the market). In theory, therefore, this mechanism can have a negative impact on productivity and growth.

This problem of a misallocation of resources in the economy is not confined to the issue of business leader gender. It also concerns minorities' access to the labour market and insufficient social mobility. These cases are all barriers to the optimal allocation of talent and the macroeconomic impact of this misallocation of resources is potentially major (Sestieri and Zignago, 2019). For instance, the work of Hsieh et al. (2019) shows that, over the period 1960-2010, 30% of economic growth in the United States came from a better allocation of the talents of women and minorities.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 7th of March 2025