In France, as in most countries and in the euro area, inflation soared in 2021-2023 to levels unprecedented since the early 80’s. A set of factors have likely contributed to this persistent burst of inflation: the global disruption of supply chains in the post-pandemic recovery, the increase in energy and food prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the tightening of the labour market. “Accounting” decompositions based on the contributions of subindices (like energy or food) to aggregate inflation, while useful, do not provide a causal explanation of inflation. For example, energy price shocks directly impact headline inflation through the prices of energy goods, but they also have indirect effects on other components. To sort out the factors contributing to inflation using a formal model is in order.

To isolate the factors that underpin inflation, Bernanke and Blanchard (2023) have developed a semi-structural econometric model, initially applied to the US economy. Under this model, the rise in inflation (just like movements in wages and inflation expectations) is attributable to shocks affecting different variables such as the tightness of the labour market (measured by the ratio of job vacancies to the number of unemployed), energy and food prices, supply chain disruptions and trend productivity. According to their analysis, the surge in US inflation from 2021 on (from 1.2% in 2020 to 8% in 2022) was mainly caused by commodity price shocks and supply chain disruptions. The tightening of the labour market was not a decisive factor for inflation until Q1 2023. However, the effects of overheating in the labour market could have materialised subsequently, given the greater persistence of higher wages. These latter considerations had initially led the authors to contend that the ‘last mile’ on the road to achieving the Federal Reserve's 2% inflation target could have been harder than anticipated.

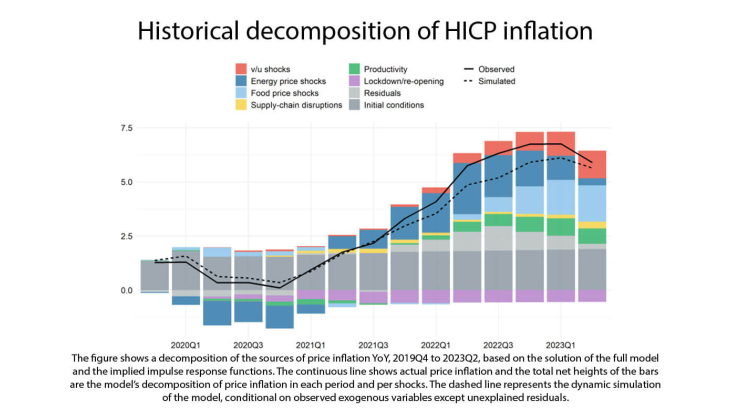

We replicated this exercise for France and estimated the Bernanke and Blanchard (2023) model using quarterly data from Q1 1990 through Q2 2023. Overall, our results (see Figure below) corroborate Bernanke and Blanchard's main findings when applied to France.

The sharp rise in inflation over the 2021-23 period was mainly triggered by energy price shocks in 2021. Food price shocks subsequently played a key role from 2022 onwards. By contrast, the impact of supply chain shocks remained small. However, inflationary shocks did not trigger a wage-price spiral, due to a low degree of wage indexation and a high degree of anchoring of inflation expectations, thanks to the credibility and strong response of the European Central Bank’s monetary policy. According to our findings, although the inflationary response to a commodity price shock is strong, it is short-lived. By contrast, the model shows that persistent tightness in the labour market causes persistent inflation. Interestingly, France stands apart from other advanced economies because of its price shield on energy prices, which limited and deferred price increases in France. Moreover, supply chain disruptions played a less significant role in France than in the United States.

Finally, we run conditional simulations, using the most recent data, up to 2024Q1. Looking forward, this exercise confirms that disinflation should continue in France: the inflation rate should stabilise at around 2% for a lasting period from 2025 on, i.e. at the European Central Bank's medium-term inflation target. The risks around this scenario are balanced. A sharp fall in the unemployment rate leading to persistent tightness in the labour market could push inflation back over 2%. Conversely, a continuing rise in the unemployment rate could push inflation well below 2%. Naturally, both scenarios would lead to monetary policy responses to prevent inflation from becoming too high or too low.

Keywords: Prices, Inflation, Wages, Inflation Expectations, Phillips Curve

JEL classification: E31