As the effects of global warming intensify, cities, where nearly 70% of humanity will live by 2050, face a major challenge. Climate change leads to an increase in the frequency, intensity and duration of heatwaves, even in temperate climate countries. Heatwaves once considered exceptional, such as the 2003 event in France, could become the new norm by the end of the century and occur during a larger part of summer. The urban environment exacerbates the effects of heatwaves, creating urban heat islands (UHI). Urban concentration leads to higher temperatures, especially at night because poor-quality building materials, roads, and infrastructure absorb and retain heat. UHI are also amplified by the lack of green spaces and vegetation and by the heat generated by human activities (engines, air conditioning).

Extreme temperatures can be the direct cause of death by provoking heat stroke, hyperthermia, and dehydration. Some populations are particularly vulnerable, such as older adults and young children, but also low-income people, because they present a more fragile state of health than the population as a whole. In addition, low-income populations cannot afford to leave the city during heatwaves to go to rentals or second homes, as wealthier households do. Their prime coping strategy consists in staying at their homes with poor insulation, where they lack agency over thermal situation, in particular with less means to cool their dwellings with air conditioning.

This paper presents the first analysis of climate inequality with respect to UHI in France. We measure UHI exposure among households depending on their income in the major French cities. To do so, we produce unique highly granular databases by compiling and matching finely localized data on temperature, vegetation, residential building density, height and period of construction, and households socioeconomic characteristics across nine of the largest French cities.

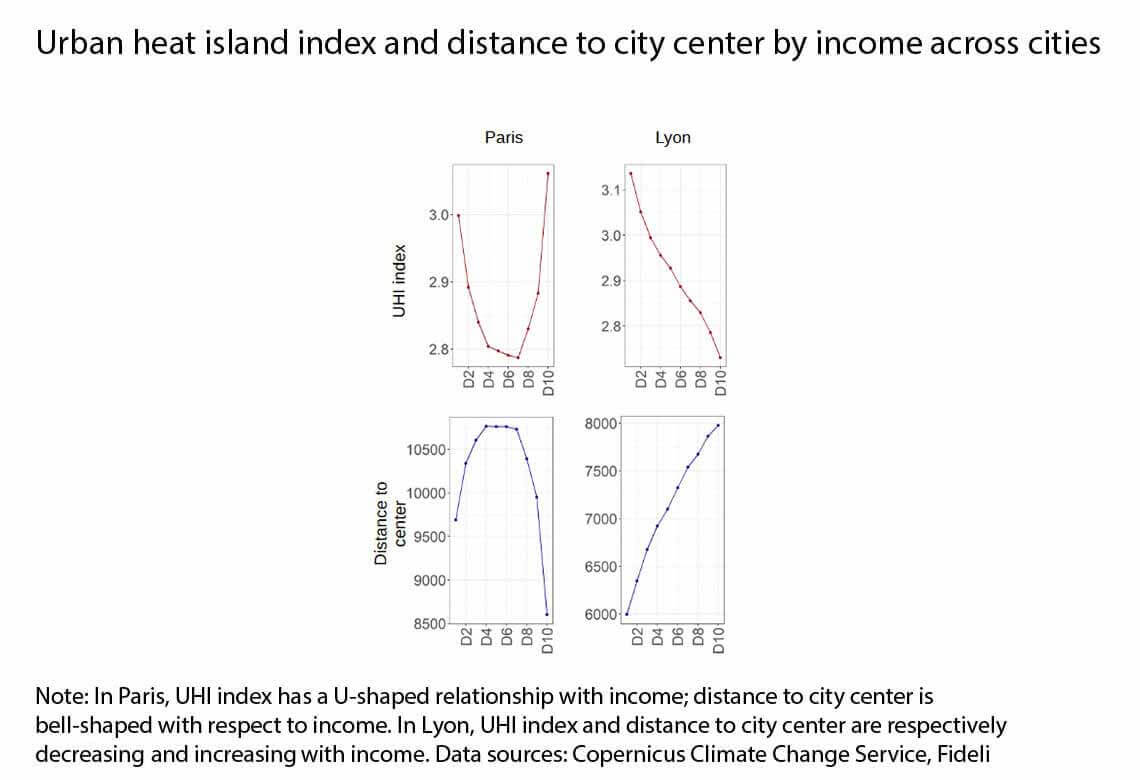

We find that the relationship between UHI exposure and income in a city depends on households spatial sorting by income. In Paris, Bordeaux, Lille, and Nantes, high- and low-income households live closer to the city center than median-income households, and UHI exposure follows a U-shape curve, particularly pronounced in Paris. In Lyon, Montpellier, Marseille, Nice, and Strasbourg, affluent households live in rich suburbs, and UHI exposure decreases with income. We also show that in all cities, except Paris for density, wealthier households live on average in greener, less dense neighborhoods with lower buildings. In cities where wealthy households live close to the city center, they also typically reside in older neighborhoods. In contrast, in cities where they live farther from the city center, they tend to reside in newer neighborhoods.

To guide public policy interventions, we identify the primary sources of unequal exposure to UHI by income across cities and we quantify their contributions to the unequal exposure to UHI by income deciles. First, building density, then vegetation and building height contribute to a decreasing relationship of UHI exposure with income in all cities, except Paris for density. The period of residential building construction in neighborhoods partly explains the varied U-shaped in the first group of cities and decreasing curves of UHI exposure by income in the second one. Lastly, as poorer households already live in denser, less green, and taller neighborhoods on average, we warn policymakers of the potential regressive impacts that mitigating policies may have.

Finally, we focus on vulnerable households, defined on age and income criteria and find that, in all cities, they are slightly more exposed to UHI than non-vulnerable ones. This difference in UHI exposure is mainly driven by the income criterion. Besides, we show that vulnerable households are less likely to improve their home insulation as they are much less likely to own their homes, to escape the city during heatwaves as they rarely possess secondary dwellings, or to cool their dwellings as the possession of an air conditioning system increases with income. We discuss the practical feasibility of exposed households limiting their use of air conditioning, which exacerbates heat stress outdoors.

Keywords: Climate Change; Urban Heat Islands; Urban Areas; Spatial Inequalities

JEL classification: Q54; R11; R14