- Home

- Publications et statistiques

- Publications

- Towards sustainable financial inclusion ...

Post No. 398. Recent progress in financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa – and especially in bank account ownership among the most vulnerable groups – plays a crucial role in improving “financial well-being” or “financial health”. To reduce the associated risks, especially for recently banked populations, financial inclusion must be accompanied by public policies to protect these groups.

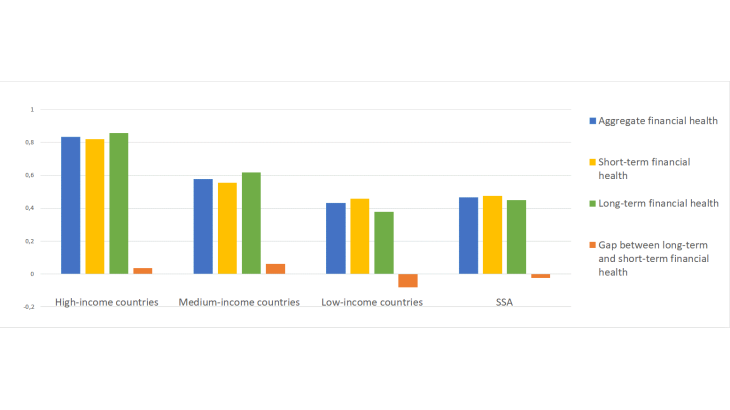

Chart 1: Short and long-term financial health in 2021 by level of development

Note: Financial health = 1 - share of individuals worried about their ability to afford spending on education or retirement (long term), monthly expenses, or expenses related to an accident or serious illness, and have difficulty raising emergency funds within 7 or 30 days (short term)

Progress in the financial inclusion of African populations can improve their financial health

A population’s “financial well-being”, or “financial health”, is primarily dependent on its economic development (see Chart 1). Financial health, defined as the ability to meet short or long-term financial obligations (GPFI, 2024), is significantly weaker in low-income countries (LICs, 43%) and in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA, 47%) than in advanced economies (AEs, 83%). In LICs and SSA, long-term financial health (i.e. the ability to meet educational and retirement costs) is also weaker than short-term financial health (the ability to meet day-to-day expenses and cope with adverse shocks), reflecting more limited access to education and less developed social safety nets. In these countries characterized by a strong preference for cash and where confidence in the formal financial system is low, a large share of financial activity still takes place via informal support networks (Guerineau, 2014). This is due notably to social, legal and cultural barriers, and, in some cases, difficulties accessing the formal financial system (too expensive, too far away, etc.). It also reflects a less developed financial system, where the offering of financial services, especially credit, is constrained by information asymmetries and by the high cost of developing infrastructure (identification of customers and creation of contact points).

However, “mobile banking” (i.e. the provision of banking services via a mobile phone) has generated significant catch-up effects in these countries. In SSA, the banked population has more than doubled in ten years, from 23% in 2011 to 55% in 2021 (41% in the WAEMU and CEMAC in 2021, compared with 8% and 12% respectively in 2011), thanks to the rapid spread of mobile banking (used by 33% of the SSA population in 2021 compared with 12% in 2014). Yet there is still room for progress in the use of certain financial services. In 2021, only 16% of the SSA population (7% in the WEAMU and 8% in CEMAC) said they held savings with a financial institution, compared with 23% in medium-income countries (MICs). Moreover, in SSA, only 10% had access to formal credit (7% in the WAEMU and CEMAC), compared with 22% in MICs. In SSA, recent rapid advances in financial inclusion could help to increase the use of financial services and improve the population’s financial health, provided this inclusion is sustainable (Dufresne, Jacolin, Salmon, 2024).

To improve populations’ financial health, financial inclusion must be sustainable

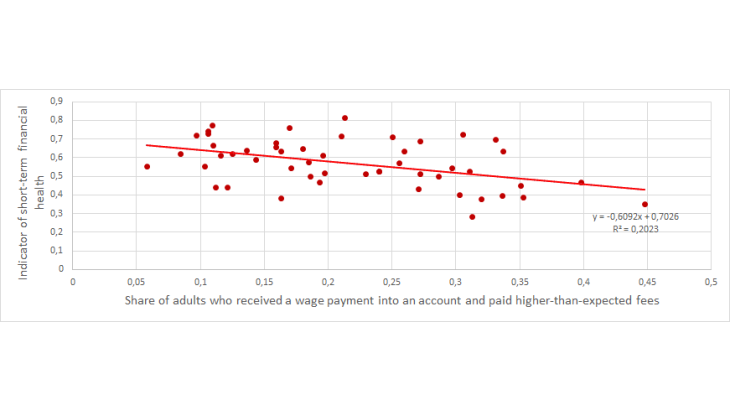

The impact of financial inclusion on financial health depends critically on the quality of the financial services offered. For SSA citizens that have only recently become banked, transparent conditions of use for digital financial services (DFS), especially regarding pricing (see Chart 2), and financial literacy are all crucial for minimising the risks linked to account ownership. The rapid spread of DFS can expose these populations to risks of fraud and overindebtedness. According to the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), nearly three-quarters of DFS users in Côte d’Ivoire experienced at least one scam attempt in 2022 (Ponzi scheme, phishing attack, etc.). In Kenya, a pioneer in digital finance in Africa, financial health is estimated to have deteriorated recently in the inflationary environment, with households turning increasingly to short-term loans which are linked to a rise in non-performing loans in the banking sector’s loan portfolio (Gubbins and Heyer, 2022).

Chart 2: Correlation between unexpected account-holding fees and financial health in emerging and developing countries

Note: Each point corresponds to a country.

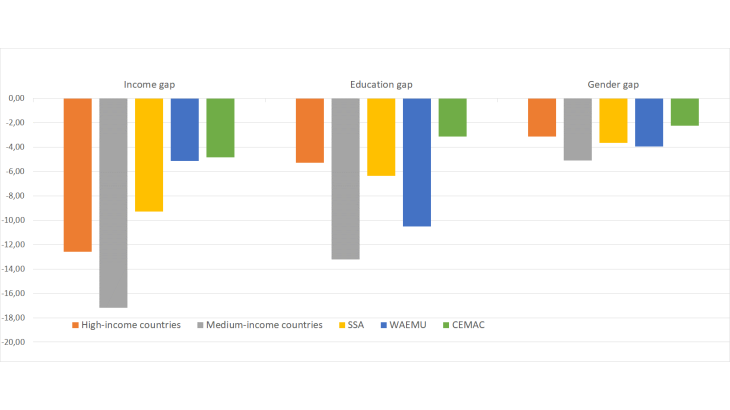

Risks are particularly acute for the most vulnerable populations. The least financially included, or “Last Mile” – the poorest, least educated and women – have the weakest financial health (see Chart 3). They are also the most vulnerable to the risks linked to sub-optimal use of financial services, and the group on which banks have the least information.

To ensure the effective and sustainable use of financial services, these information asymmetries need to be reduced – for example, by reinforcing systems to identify the population, along the lines of the Aadhaar unique ID system in India, which is a secure centralised identification system for financial institutions. Regarding credit access, the development of guarantee registers, central credit registers and credit bureaus, and especially the monitoring of mobile banking use, can all help to improve understanding of customer behaviour.

Chart 3: Differences in financial health in 2021 by level of development

Note: The income gap, in percentage points, is defined as the difference in financial health between the 40% poorest individuals and the 60% richest individuals. The education gap is defined as the difference in financial health between those with primary education at the most and those with at least secondary education. The gender gap is the difference in financial health between women and men.

Towards high-quality financial inclusion and financial health in SSA

Improving access to secure financial infrastructure can amplify the catch-up effects generated by mobile banking. The current roll-out of rapid, interoperable payment systems (AfricaNenda, 2022), such as the Pan African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) in the African Union, the Groupement Interbancaire Monétique de l’Afrique Centrale (GIMACPAY) in the CEMAC, and, more recently, Pi in the WAEMU, will be important in expanding and lowering the cost of DFS in SSA: national financial markets in these countries are small and fragmented, and significant gains can be made from financial integration. Another contributing factor will be the international efforts underway to harmonise cross-border payments, such as the G20 2027 roadmap and the recommendations from the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion’s (GPFI) report on digital public infrastructure. The G7 partnership for the digital financial inclusion of women in Africa, set up under the French presidency in 2019, aims to improve digital identification and payment system interoperability.

Another key to improving financial health in Africa is financial literacy; however the barriers to education are greater in these countries than in AEs. The need to promote financial literacy has in general been properly identified, with two-thirds of SSA countries implementing a financial literacy strategy and digital education programmes comparable to those in AEs. But it can prove difficult to target vulnerable populations in these countries, due to lower access to education (only 44.8% reach secondary education, according to the World Bank), limited fiscal leeway and the need for technical assistance.

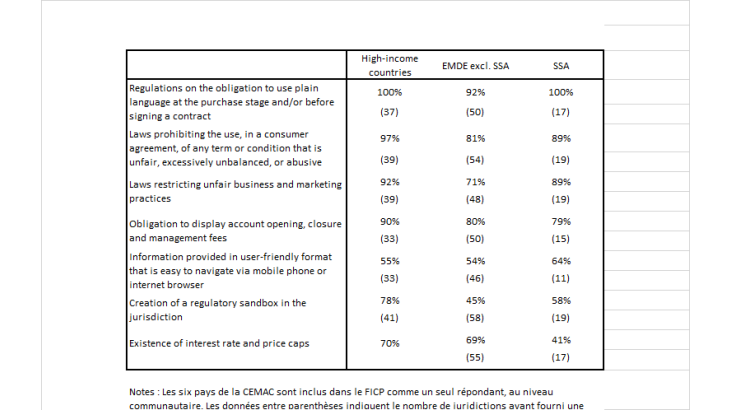

Another essential lever for ensuring sustainable financial inclusion is consumer protection regulation. Even though some regulations have indeed been adopted widely in SSA (see Table 1), rules restricting prices, and especially usury laws, are less widespread than in other countries (41% of SSA countries have them compared with 70% of high-income countries in our sample). For DFS to expand rapidly, it is also important to adapt existing regulations, notably to include new player categories such as electronic money issuers and payment institutions. There are also fewer sandboxes in SSA than in AEs (58% of countries compared with 78%). Fewer SSA countries have adopted open banking standards (16% compared with 56%), which can help to improve customer knowledge – provided the associated risks are taken into account, especially regarding data privacy.

Table 1: Consumer protection regulations

Notes: The six CEMAC countries are grouped together as a single respondent. Data in brackets show the number of jurisdictions that provided a response.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 3rd of July 2025