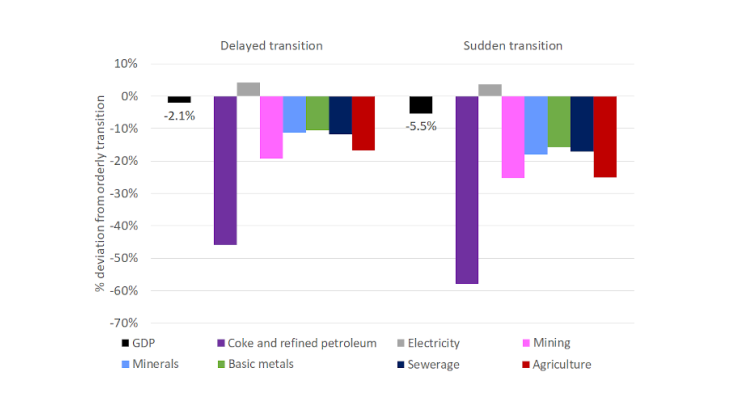

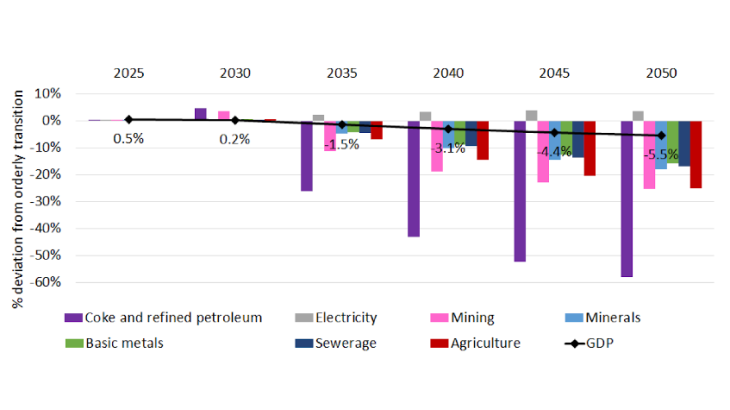

Note: Impacts in deviation from the orderly transition. For example, in the event of a sudden transition, the GDP and value added of the “Mining” sector in 2050 would be 5.5% and 25% lower respectively than under an orderly transition.

Although there is still some debate over the best way of achieving an efficient climate transition, the risks of a “disorderly” transition (for example acting too late or, conversely, too suddenly) are far less contested. It is nonetheless important to quantify these risks, in order to better anticipate the resulting economic and financial challenges. So-called “orderly” transition scenarios, where economies succeed in making the shifts needed to meet the Paris Agreement goals, frequently anticipate that the costs to the economy will be low (see the French National Low-Carbon Strategy or the Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System’s orderly transition scenario, which estimate that the final impact on French GDP by 2050 will be negligible). One possible criticism of these analyses is that they take insufficient account of certain macroeconomic costs during the transition phase (Pisani-Ferry, 2021). The aim of this blog post is not to discuss these scenarios but rather to underline the risks associated with a disorderly transition, using as a basis the climate pilot exercise conducted by the ACPR in 2021. For this exercise, the Banque de France developed a suite of models that disaggregate the effects of the low-carbon transition at the national, sectoral and infra-sectoral levels. There are specific requirements for the exercise, notably a very long time horizon and high degree of granularity in order to capture disparities that are invisible at the macroeconomic level.

Transition scenarios

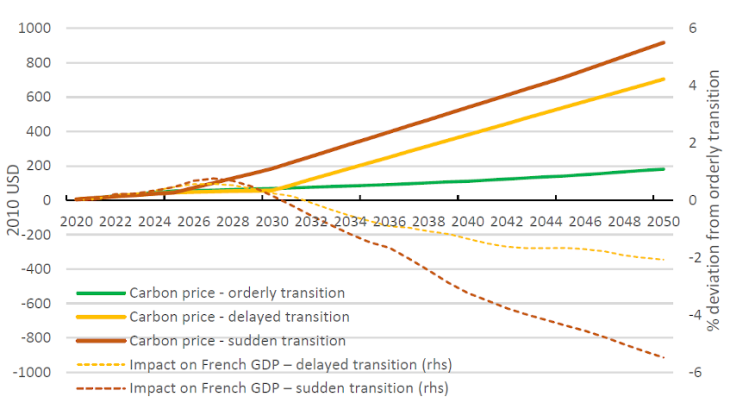

Within the framework of the ACPR’s pilot exercise, Allen et al. (2020) describe three types of climate transition: (i) an “orderly” transition where public policy action and technological change reduce carbon emissions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement, with minimum macroeconomic damage; (ii) a “delayed disorderly” transition involving delayed policy action and disruptive effects on the economy; and (iii) a “sudden disorderly” transition where the late and abrupt (to make up for the delay) implementation of the transition is not accompanied by technological advances, leading to significant disruptive effects.

In this blog post, we present the two latter scenarios (Chart 2), with a particular focus on the “sudden” adverse transition. The impacts of the two transitions are measured as deviations from the orderly transition, i.e. the one that meets the Paris Agreement goals with no major disruption, and where the carbon price rises from EUR 54 per tonne of CO2 equivalent (tCO2eq) in 2025 to EUR 180 in 2050. The “sudden” transition scenario is based on a rise in the carbon price, via increased taxes, from EUR 45 tCO2eq in 2025 to over EUR 900 in 2050, which is nearly EUR 700 higher than in the orderly transition. It can therefore be considered to be strongly adverse, as this carbon price shock is only accompanied by minimal technological progress.