- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- Short-time work: a useful tool in times ...

Post n°158. The short-time work mechanism has recently been bolstered to limit the repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic on employment. By preventing dismissals due to temporary difficulties, the reduction in hours worked allows firms to preserve their human capital and will foster the resumption of activity. Certain windfall effects should nevertheless be avoided, outside crisis periods, even though they generally remain minor compared with the benefits of such schemes during times of crisis.

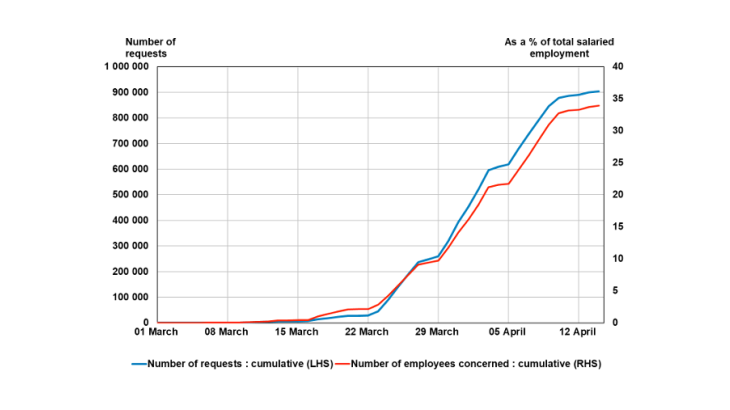

Source: Dares.

Note: In France, the number of requests for short-time work due to Covid-19 amounted to 904,000 at 14 April 2020, representing 8.7 million employees (34% of salaried employment).

Short-time work, more commonly known as chômage partiel in France and Kurzarbeit in Germany, enables firms facing temporary difficulties to reduce the number of hours worked by all or some of their employees. These workers receive compensation for these unworked hours, which is partly or fully financed by the government.

The use of short-time work has reached unprecedented levels due to the Covid-19 pandemic

Since the beginning of March 2020, the public health emergency unleashed by Covid-19 has led many governments, notably French and German, to restrict the movement of their citizens and to order the closure of businesses deemed "non-essential". These restrictions have brought a large part of the economy to a standstill.

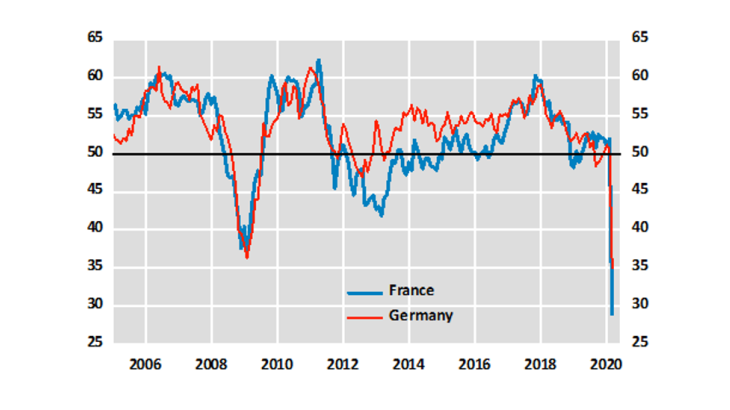

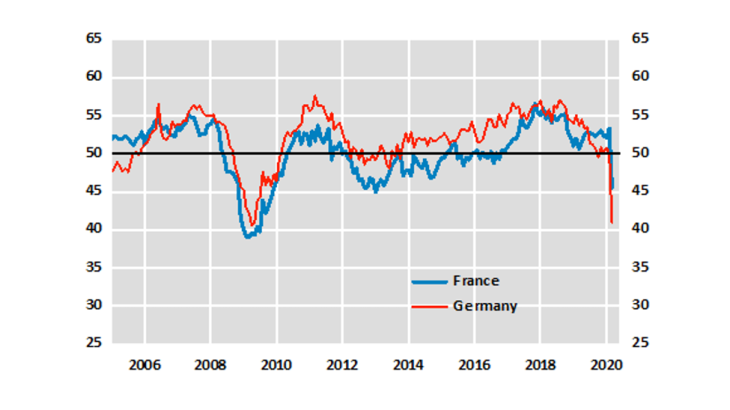

The first economic indicators available for March 2020 show an unprecedented month-‑on-‑month drop in activity. The composite PMI (Chart 2a) reached a historical low in France, at 28.9 (down 23 percentage points on February), as well as in Germany at 35.0 (down 16 percentage points month-on-month). The employment component, which accounts for 20% of the total index, also experienced an unprecedented decline in March (down 8 percentage points in France and 9 percentage points in Germany (Chart 2b), particularly in services). In its March 2020 business assessment, the Banque de France estimated that every two weeks of lockdown results in a loss of annual GDP of approximately 1.5%.

The French and German governments have reformed the short-time work scheme in order to encourage its use and dampen the economic shock. In France, unworked hours are now fully funded by the government and Unédic (the body charged with managing unemployment benefit), up to a maximum of 4.5 times the hourly net minimum wage. The application procedure has been simplified, in particular by reducing the time taken to process requests. According to the Dares weekly indicator at 14 April 2020, 732,000 companies and almost 8.7 million people were benefiting from short-time work, i.e. 34% of salaried employment.

In Germany, the mechanism has been extended to temporary workers and the application procedure has been simplified: a company will be able to apply for short-time work if at least 10% of its employees are potentially affected by a work stoppage (compared to 30% previously). Other constraints, related to the use of employees' working time accounts, have also been relaxed. Since the start of the pandemic (as at 13 April), 725,000 firms have applied to the Federal Employment Agency for short-time work, compared with 1,900 in February.

A tried and tested mechanism during the Great Recession

Short-time work had already been used to protect employment during the Great Recession of 2008-09 in France and even more in Germany (Cahuc et al., 2018 and Balleer et al., 2016, respectively). In Germany, the implementation of collective agreements on working time and wages made a major contribution to the labour market "miracle” (Barthelemy and Cette, 2011 ; Boulin and Cette, 2013).

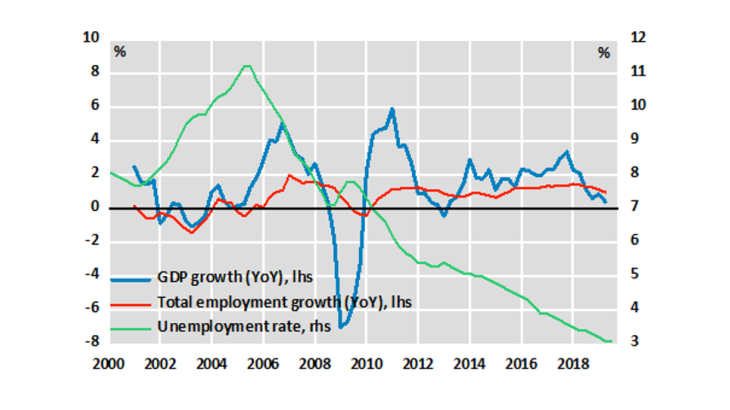

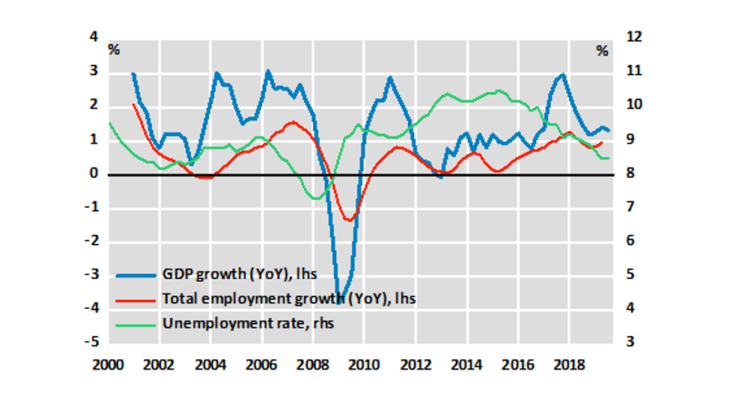

For example, GDP fell by 5.6% in 2009 in Germany without leading to a collapse in employment or a surge in the unemployment rate (Chart 3a). In France, GDP fell less sharply (-2.8%), but job losses were higher and the unemployment rate rose on a sustained basis (Chart 3b). On average, in 2009, the use of short-time work for economic reasons affected 3.0% of employees in Germany, compared with 1.3% in France.

However, legislation differs in France and Germany

In both countries, employees receive compensation for each unworked hour of between 60‑84% of their net hourly wage. This compensation may not, however, be less than the hourly minimum wage in France. The maximum length of compensation is now limited to 12 months in France, and up to a maximum of 1,607 hours per employee per year. In Germany, it can be extended by decree, depending on the economic situation of the country or of a particular sector.

There are three main differences in terms of legislation between France and Germany, which have become less pronounced since the Covid-19 crisis. First, short-time work includes non‑standard contracts such as fixed-term contracts and temporary workers in France, whereas in Germany it does not cover mini-jobs and temporary workers have only been taken into account as of April 2020. Second, in France, payments are made by firms, which are then reimbursed by the government and Unédic:-- up to EUR 7.23 per hour for firms with more than 250 employees and EUR 7.74 per hour for smaller firms. It should be noted that, since 17 March, this compensation has been fully covered. In Germany, compensation is fully funded by the public authorities, thus easing the financial constraints of companies. This difference seems to explain the greater take-up of short-time work in Germany in 2009. Third, in France, it is up to the administration to assess the level of difficulties, whereas in Germany the scheme includes thresholds for triggering the short-time work mechanism based on the proportion of employees and/or the number of hours concerned, which makes it possible to identify troubled firms more effectively. Businesses must also have exhausted all other options that could have allowed them to avoid using the short-time work mechanism. These conditions have been partially eased since the start of the Covid-19 crisis.

A widely adopted mechanism in a locked-down Europe

In Europe, short-time work is a flagship measure to combat the Covid-19 crisis. Many European countries have made reforms to this mechanism or have created such a scheme (Greece, Sweden). For instance, in Austria, Belgium, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, this scheme is generally more generous towards employees and/or companies; in Austria, Spain and Finland, the procedure has been simplified; and, in Spain, the scope has been extended to benefit certain categories of previously excluded employees.

In order to encourage these initiatives, the European Commission announced on 2 April 2020 the creation of a financial assistance mechanism designed to protect the jobs threatened by the pandemic. Its proposed budget will be EUR 100 billion in the form of guarantees and soft loans to Member States in order to promote the creation or extension of national schemes such as short-time work.

However, while it protects jobs, the short-time work scheme may also have perverse effects, particularly if it is used for extended periods outside times of crisis. Some firms not experiencing difficulties may be tempted to take advantage of it to make a profit, putting a strain on public finances with a negative effect on hours worked without any gain in employment (windfall effect). Other firms, facing structural difficulties, would be tempted to use it, which delays or even prevents the reallocation of their labour force to more productive sectors. These negative effects result in a loss of aggregate output relative to the social optimum (Cahuc and Nevoux, 2018 ; Cooper et al., 2017). However, these effects remain relatively modest compared to the benefits of short-time work in times of crisis.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024