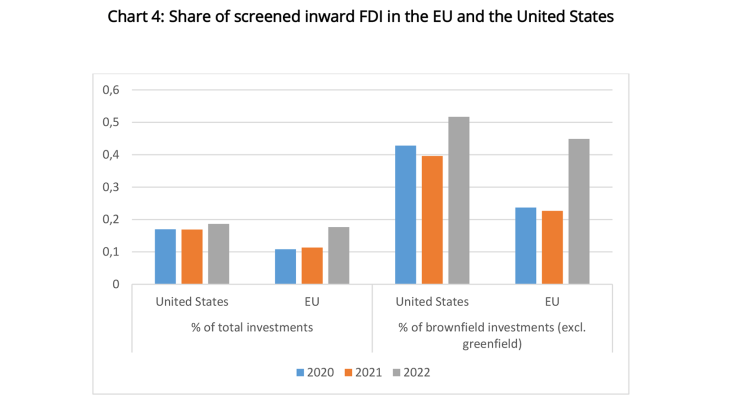

The increasing use of ISMs in the EU has contributed to the growth in the number of transactions screened in 2022. However, in both the United States and the EU, few transactions are blocked (1% in the EU, no transactions in the United States in 2022), which suggests that ISMs strike a balance between opening up to FDI and protecting national interests. The low percentage of transactions blocked could also reflect the deterrent effect of ISMs.

Information and communication technologies and the manufacturing sector account for the bulk of transactions screened or blocked, which is consistent with the scope of MFIs. These sectors include technology (artificial intelligence, robotics, etc.), critical infrastructure (communications, media, data processing and storage) and defence.

The geographical origin of the most screened investors is related to the weight of each nationality in FDI flows (the share of US investments in investment flows to the EU, and vice versa). However, in the United States as in Europe, some investments, particularly from China and Russia, are over-represented in the transactions that are screened and blocked. This over-representation reflects the predominance of Chinese investors controlled by state authorities and subject to particularly close monitoring in most ISMs.

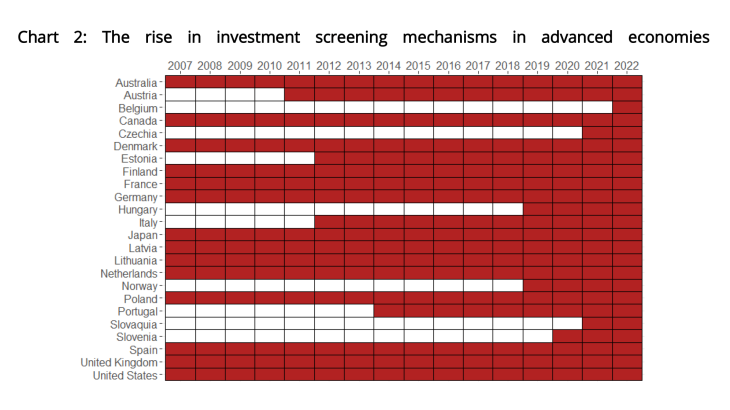

The trend towards stricter FDI screening mechanisms continues apace. In the United States, the Biden administration announced in summer 2023 the creation of a screening mechanism for outward FDI, designed to limit the risk of technology transfers with potential military applications. The EU has affirmed its commitment to strengthening its economic security and analysing the risks posed by outward investments in its European Economic Security Strategy (June 2023).