From “too-big-to-fail” to global systemically important banks

Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the G20 called for the implementation of measures to address the problem of large international banks whose failure could cause disruption to the financial system and to real economic activity. In November 2011, the Financial Stability Board identified 29 global banks deemed to be systemically important due to their size and complexity, the lack of readily-available substitutes for the financial services they provide to the economy, their interconnectedness with the financial system and the scale of their cross-jurisdictional activity. These banks were required to comply with stricter capital requirements than those set out in Basel III. A special system of oversight and supervision was also set up to prevent their failure or ensure their orderly resolution, and thus limit the need for government intervention.

Have the G20’s reforms achieved their objectives ?

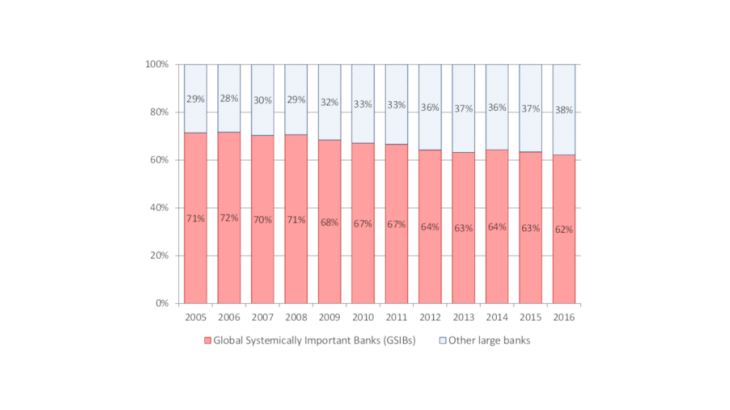

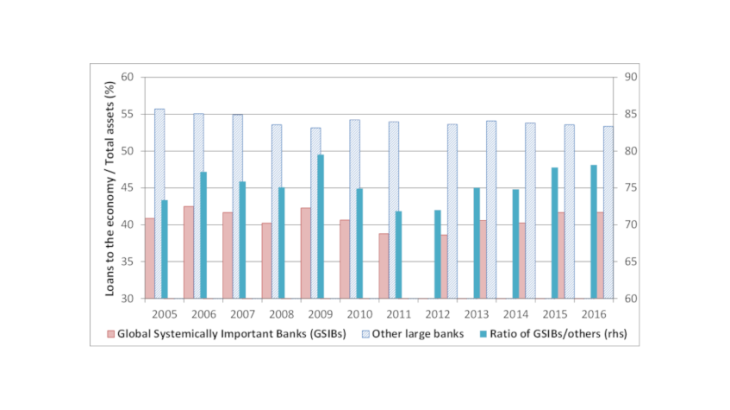

Eight years after the first GSIBs were designated, it is useful to check whether the regulations have had the desired effect. We therefore attempted to assess to what extent the changes in GSIBs’ activities differ from those experienced by other large banks, taking into account initial structural differences between the two types of institution and the financial and macroeconomic events that have affected the countries where they are based. To do this, we analysed the balance sheets of 97 large banks in 22 countries over the period 2005-16, and identified the differences between GSIBs (34 banks designated as GSIBs at least once over the period under review) and other banks before and after 2011. We focused in particular on whether GSIBs have maintained their ability to finance the real economy.

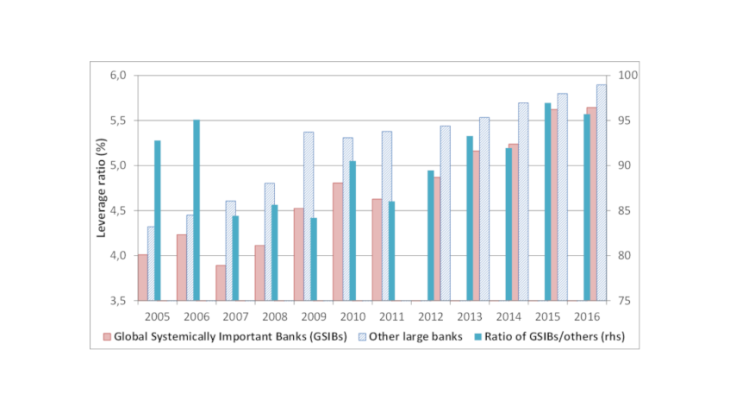

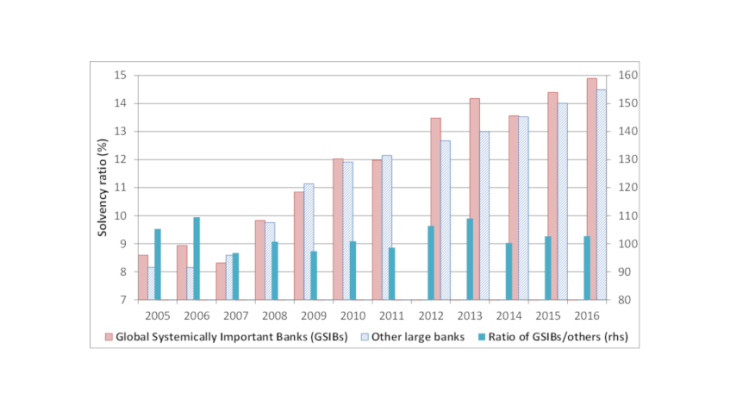

GSIBs have expanded their balance sheets to a lesser extent than other banks

The Basel III framework, which also took effect as of 2011, required all banks, including GSIBs, to increase their leverage and solvency ratios. All financial institutions increased their own funds with a view to meeting these requirements, and GSIBs were no exception. However, GSIBs had much lower leverage ratios than other banks prior to 2011 and increased them at a faster pace in the period after this date (see Chart 2). They also curbed their balance sheet growth to a much greater extent than other banks, leading to a narrowing of the gap between the two categories. This was one of the objectives of the G20, as low leverage ratios can imply a need for government support.