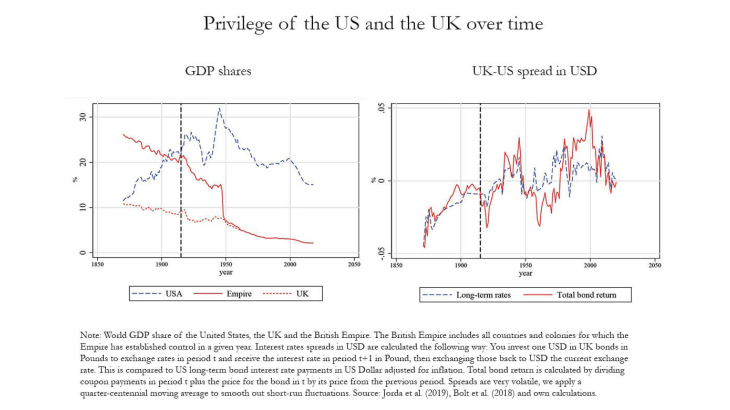

How does a country obtain the status of a dominant global currency provider, and how can it lose this position? This paper focuses on two key aspects: safety and size, and how they relate to each other. Both are necessary conditions for becoming a dominant global currency, in which a country enjoys an exorbitant privilege in the form of lower yields. This is the result of investors strongly preferring to hold bonds of the dominant country, thus willing to pay lower interest rates to the country with the dominant currency.

Our point of departure is that government bonds are not per se safe, as governments can default on their debt whenever a shock occurs that makes it tempting to do so. We argue that a larger economy helps to diversify this default risk. We discuss how regional and sectoral correlation of idiosyncratic shocks, as well the institutional features of the government are key to this diversification argument.

Next to safety itself, the overall size of the country also plays a role as a larger financial market makes it easier to facilitate transactions. This makes bonds of a large country more attractive, which means that there are interest rate spreads even in situations in which countries are comparably safe, but of different size. Furthermore, having safer government bonds also increases the debt capacity of a country, which allows for higher sustainable debt to GDP ratios. This amplifies the size effect and creates convenience yields.

Interest rate differentials are then composed of both a risk and a liquidity premium. While abundant supply of bonds is good from the perspective of liquidity provision, there is a trade-off as the country's risk premium increases at the same time. As in the Triffin dilemma, a country that acts as the global liquidity provider needs to be prudent not to overextend itself.

A previously dominant country can lose its exorbitant privilege if it is eventually overtaken by another rising country in terms of size and safety. The paper highlights several key factors that determine when a challenger could be ready to assume that role, and when it might not. The challenging country would need to have sufficient size, diversification, institutional quality and financial development.