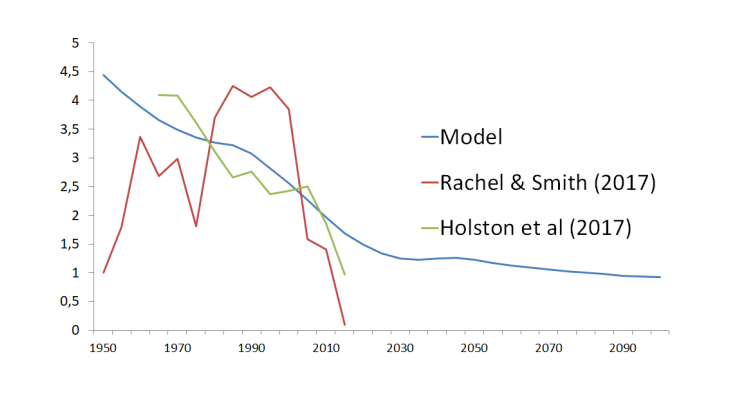

In the model, demographic change implies a decrease in the annual interest rate by 157 basis points (bps) between 1980 and 2015, and is forecast to push down interest rates by a further 76bps by 2100. Compared to measures of the natural interest rate evolution between 1980 and 2015 obtained from the data, demographics are able to replicate 75% of the roughly 210bps drop estimated by Holston et al. (2017), and around 45% of the fall in the Rachel and Smith (2017) measure.

The key mechanism triggered by the demographic transition is the following. First, households anticipate that they will live longer and spend more time in retirement. They are therefore willing to transfer more of their income during working life to the future, in order to smooth their consumption. Second, the slower population growth and increased longevity imply that older households make up a larger share of the total population alive at each period. These two changes both increase the level of aggregate savings-to-GDP over time. To keep the capital market balanced given this higher capital supply, the interest rate decreases.

Unsurprisingly, demographic change alone cannot explain the whole interest rate fall since 1980 which leaves room for other, possibly more transitory, explanations of the current low level of interest rates. Yet, the demographic changes themselves do not reverse, and leave the economy with a permanently lower natural interest rate, as highlighted by the slowly decreasing trend in interest rates after 2030.

Second, our theoretical set-up allows for a broader diagnostic on the impact of ageing on housing wealth, housing prices, household debt-to-GDP and external net foreign assets position. Besides the utility they derive from housing, households can use it as an additional way of transferring wealth over time, in that it is durable and can be sold to fund consumption and bequests. As the interest rate falls, demand for housing rises, pushing up housing prices and increasing the housing wealth-to-GDP ratio.

To be able to afford the more expensive housing assets, young households have to borrow more, and so the rising house price contributes to the rising household-debt-to-GDP ratio. The lower interest rate also has a similar effect as it encourages more borrowing by the young, raising net household debt-to-GDP. Although this pushes down on aggregate savings-to-GDP, it is not strong enough to compensate the increase in savings implied by the change in the structure of the population, hence the increase in aggregate savings and decrease in interest rate along the transition path.

Last, extending our model to consider countries with different ageing speeds, we show that countries ageing faster (e.g. Germany) will accumulate positive net foreign assets, while the opposite is true for countries ageing at a slower pace. About 20% of the cross-country variations in net foreign assets-to-GDP can be explained by demographics in our model.