1. A simple definition but a complex reality

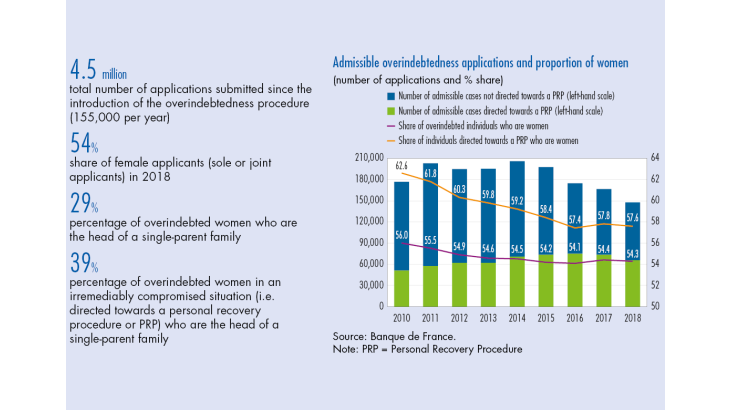

The overindebtedness procedure was introduced under Law No. 89-1010 of 31 December 1989, known as the Neiertz Law, and will thus be 30 years old at the end of this year. It aims to find solutions for families and individuals who are struggling to repay debts or to meet their day-to-day expenses. The laws in place for helping overindebted families, the methods used to deal with cases and even the goals of the procedure have all undergone profound changes over the years.

Main changes in the procedure since its creation

The procedure was initially designed to resolve difficulties deemed to be transitory: the emergence of a high number of cases of overindebtedness not linked to a professional activity, in a context of surging consumer credit following the deregulation of lending in France. The procedure originally consisted exclusively of finding an amicable settlement between debtors and creditors, under the supervision and guidance of the household debt commissions. However, the continuing problem of overindebtedness combined with the high failure rate for the procedure, prompted the authorities to introduce a first set of reforms in 1995 giving the commissions a greater role. Under these changes, the commissions were given responsibility for issuing recommendations to the courts in the event of a breakdown in amicable settlement talks. Subsequent legal changes granted the commissions even greater powers: in 1998 they were authorised to propose debt moratoriums for a limited period; in 2004, the personal recovery procedure was introduced, under which an applicant’s debts can be completely written off, subject to court approval, if the situation is found to be irremediably compromised; and in 2010 the commissions were given the power to impose debt resolution measures on both parties, again under the supervision of the courts. More recently, from 1 January 2018 onwards, two new laws took effect that simplify and speed up the overindebtedness procedure and grant the commissions’ even greater independence: the amicable settlement phase is now reserved exclusively for cases where the debtor owns real estate; and court approval is no longer required for debt resolution measures imposed by the commissions or for personal recovery procedures not involving a judicial liquidation. If the debtors or creditors disagree with the commissions’ decisions, they still have the option of lodging an appeal before a court.

[To read more, please download the article]