- Home

- Publications et statistiques

- Publications

- Macroeconomic projections – December 202...

In order to contribute to the national and European economic debate, the Banque de France periodically publishes macroeconomic forecasts for France, constructed as part of the Eurosystem projection exercise and covering the current and two forthcoming years. Some of the publications also include an in-depth analysis of the results, along with focus articles on topics of interest.

- Our new macroeconomic projections were finalised in an increasingly uncertain national and international context. This projection was drawn up on 27 November, i.e. prior to the no-confidence vote, using assumptions relating to public finances close to those of the draft Budget Act, leading to a significant reduction in the government deficit to 5% of GDP in 2025. However, less fiscal consolidation would not lead to more growth as the negative effect of heightened uncertainty on household and business demand would have the opposite effect.

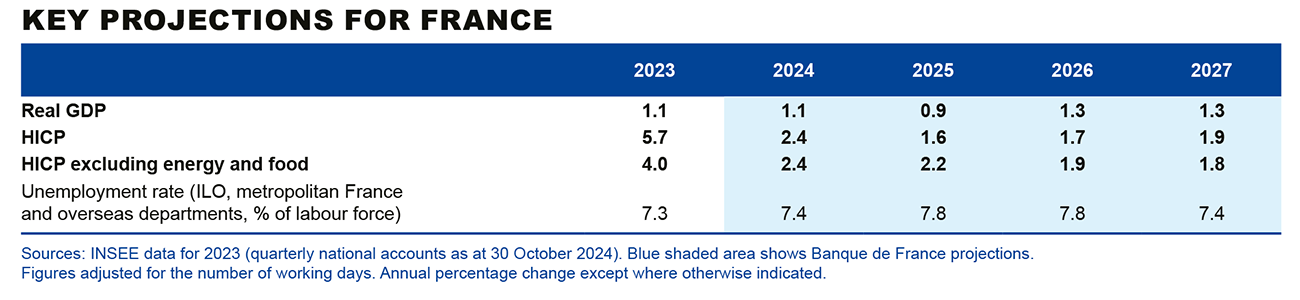

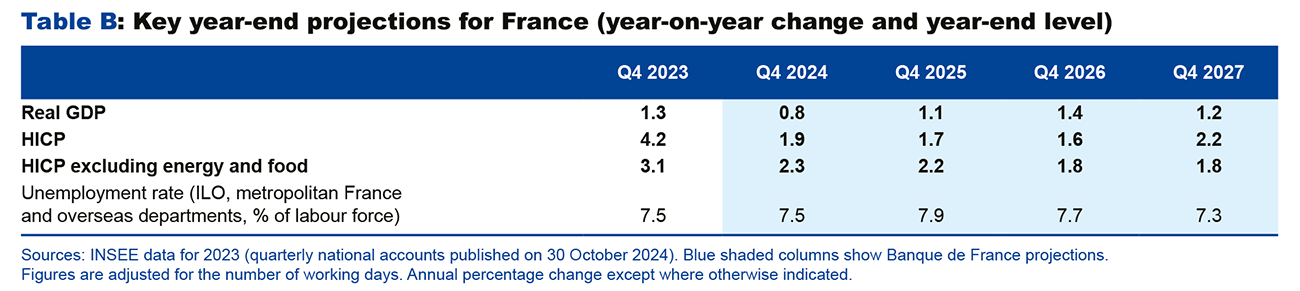

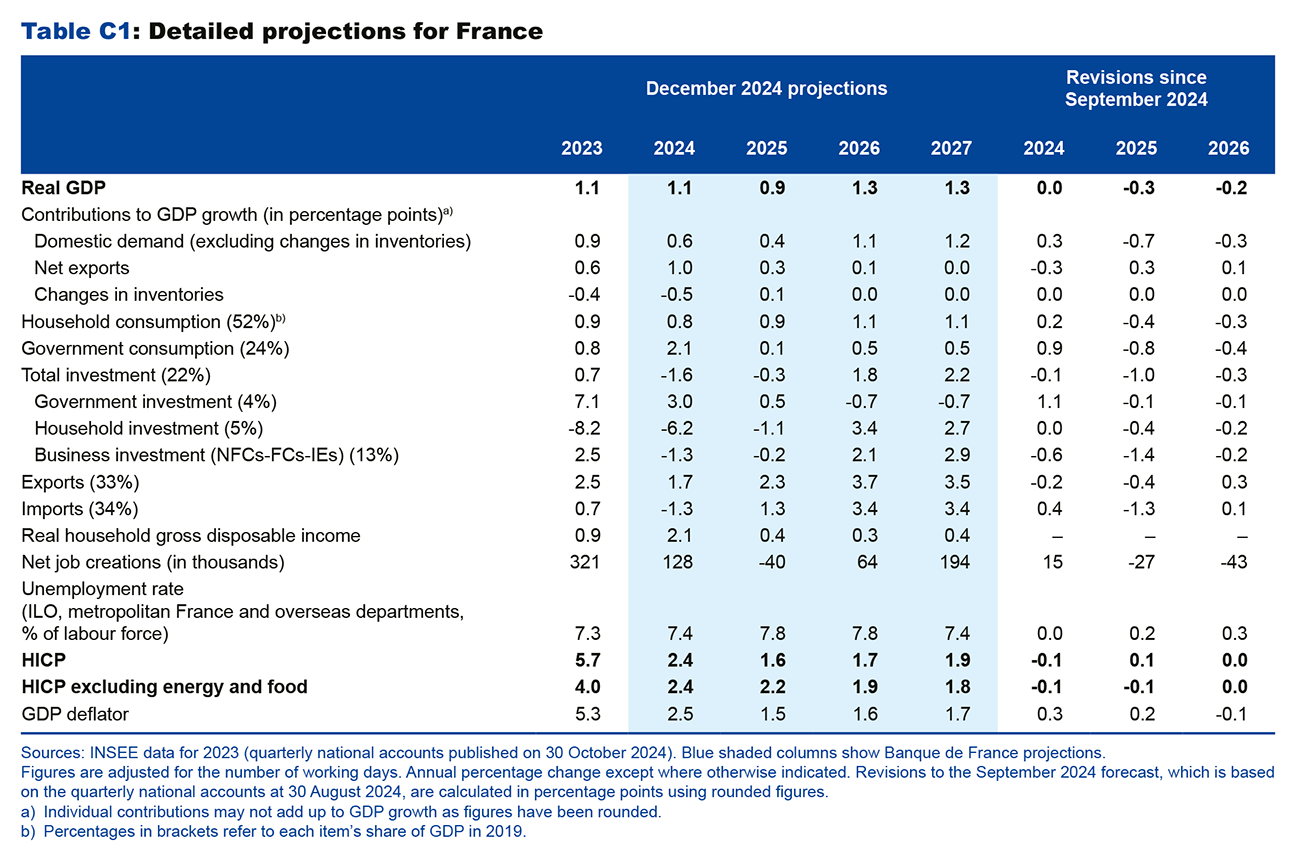

- Our baseline scenario remains that of an exit from inflation without a recession, with a recovery delayed until 2026 and 2027, when compared with our previous projections. Economic activity is expected to grow by 1.1% in 2024, driven mainly by foreign trade. Growth should remain positive in 2025 but decline slightly. In line with the expected recovery in demand from our European partners, growth should pick up in 2026 and 2027, essentially under the effect of lower inflation, and the loosening of monetary policy that will have taken place.

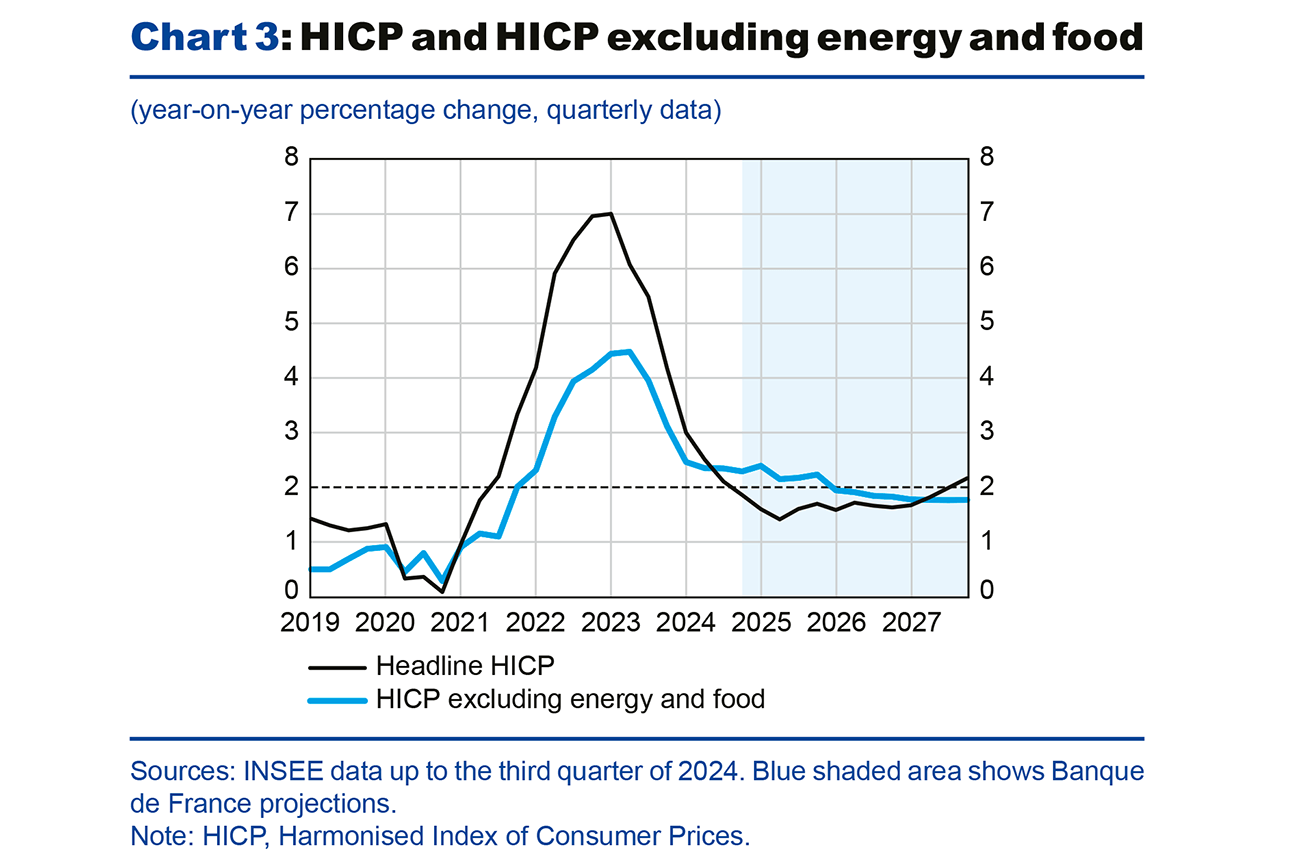

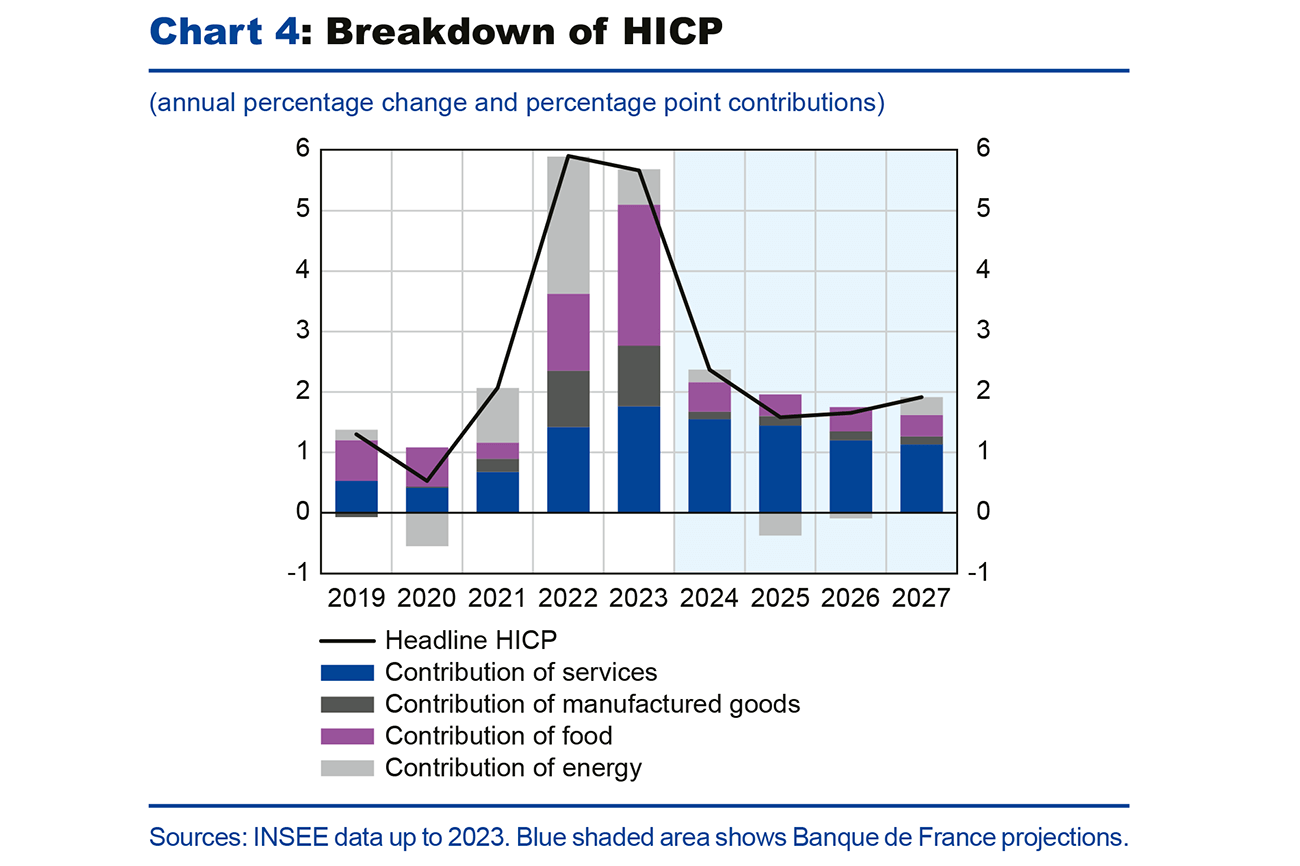

- In 2024, headline inflation declined significantly and is expected to fall to an annual average of 2.4%. Over the projection horizon, inflation should stay below 2% for a lasting period. This slowdown in prices should be facilitated by a slowdown in food, energy and manufactured goods prices, while inflation in services should fall more slowly, thus accounting for a more gradual decline in core inflation towards 2%.

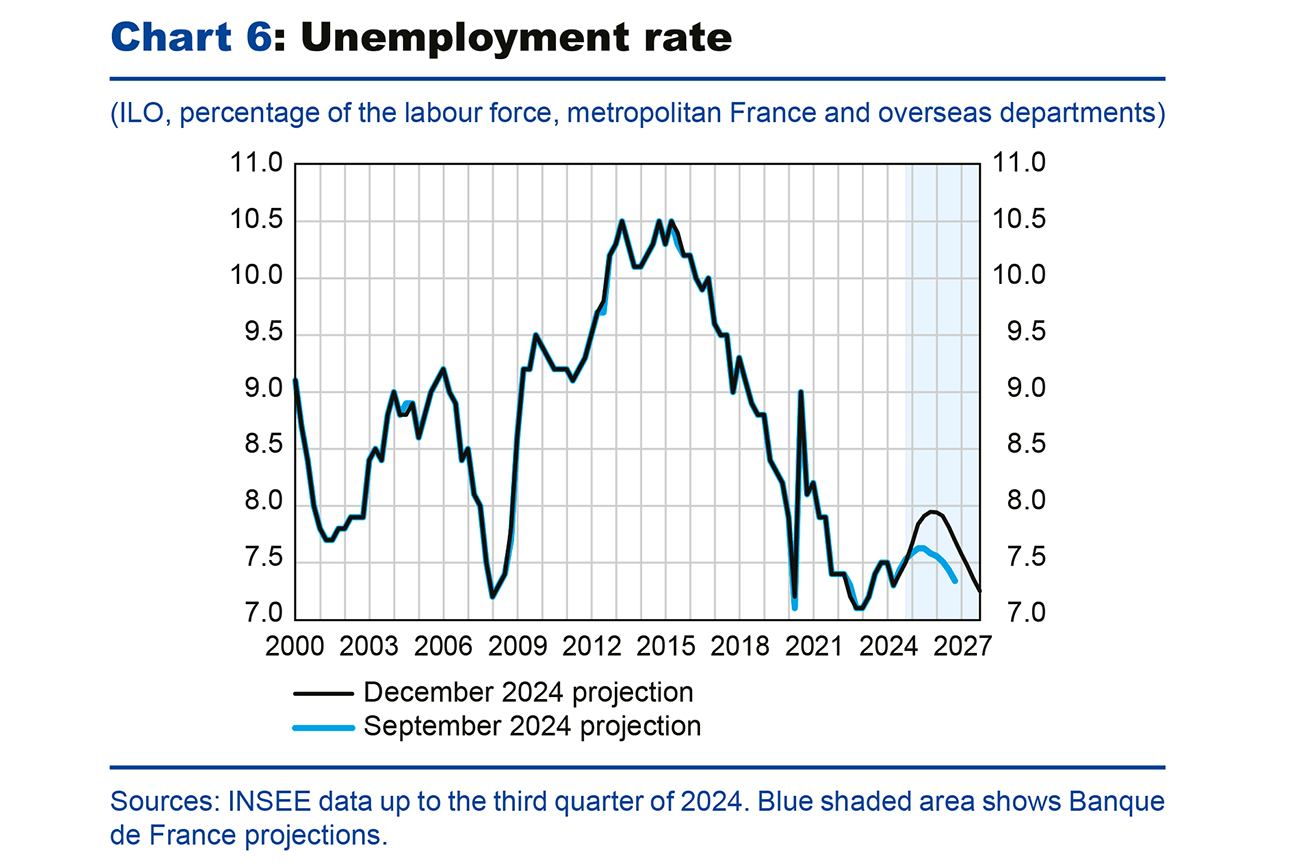

- As expected, the labour market is starting to enter a transitional slowdown phase, concentrated in 2025. The unemployment rate should peak at below 8% in 2025 and 2026, before declining again as activity picks up.

- In addition to domestic uncertainties, geopolitical uncertainties remain high, as do those weighing upon international trade. Our baseline scenario does not take into account the risk of trade tensions in the event of an increase in US customs duties, the effects of which are difficult to quantify (see Box). Overall, the risks relative to our projection are on the downside for growth, and to a lesser extent for inflation.

Projections macroéconomique 2024-2027 – Décembre 2024

Growth is expected to stay positive but decline slightly in 2025, before picking up in 2026

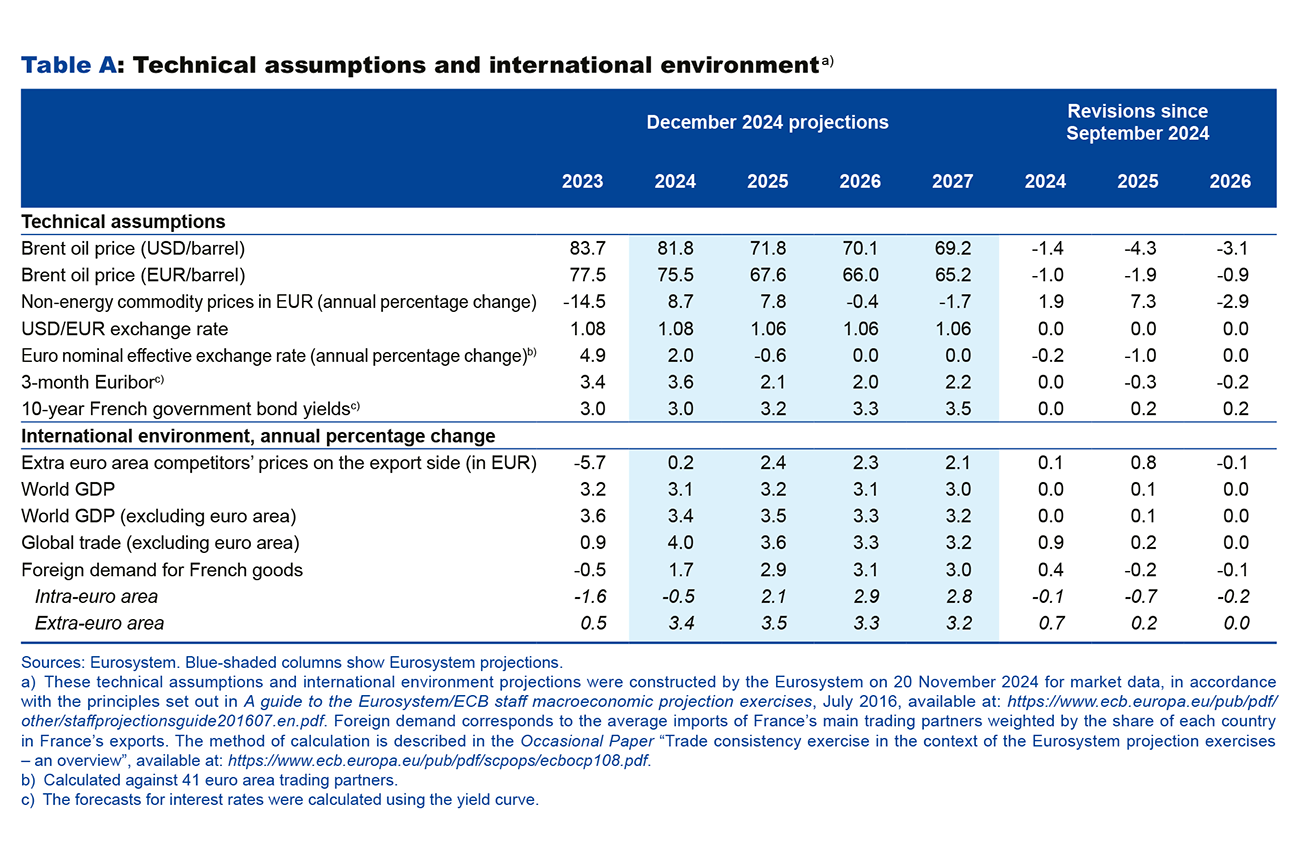

This projection, which was finalised on 27 November 2024, incorporates the first estimate of the third quarter 2024 national accounts published on 30 October, and the final estimate of HICP (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices) inflation for October published on 15 November. It is based on the Eurosystem’s technical assumptions, for which the cut-off date is 20 November 2024. It does not take into account the detailed figures for the third quarter of 2024, but these are broadly in line with our forecasts, with growth carry-over at the end of the third quarter remaining unchanged at 1.1%. Furthermore, our international scenario incorporates a more expansionary fiscal policy in the United States following the outcome of the US elections, but does not take into account the impact of tariffs, which remain uncertain at this stage.

Finally and most importantly, our fiscal assumptions for 2025 are based on the French government’s initial draft Budget Act presented to the Council of Ministers on 10 October. However, our projections remain in line with alternative assumptions leading to a higher government deficit, based on a working assumption of between 5% and 5½% of GDP in 2025 (see the section on public finances). The greater uncertainty arising from the budgetary position would compensate for the more limited magnitude of the fiscal restraint.

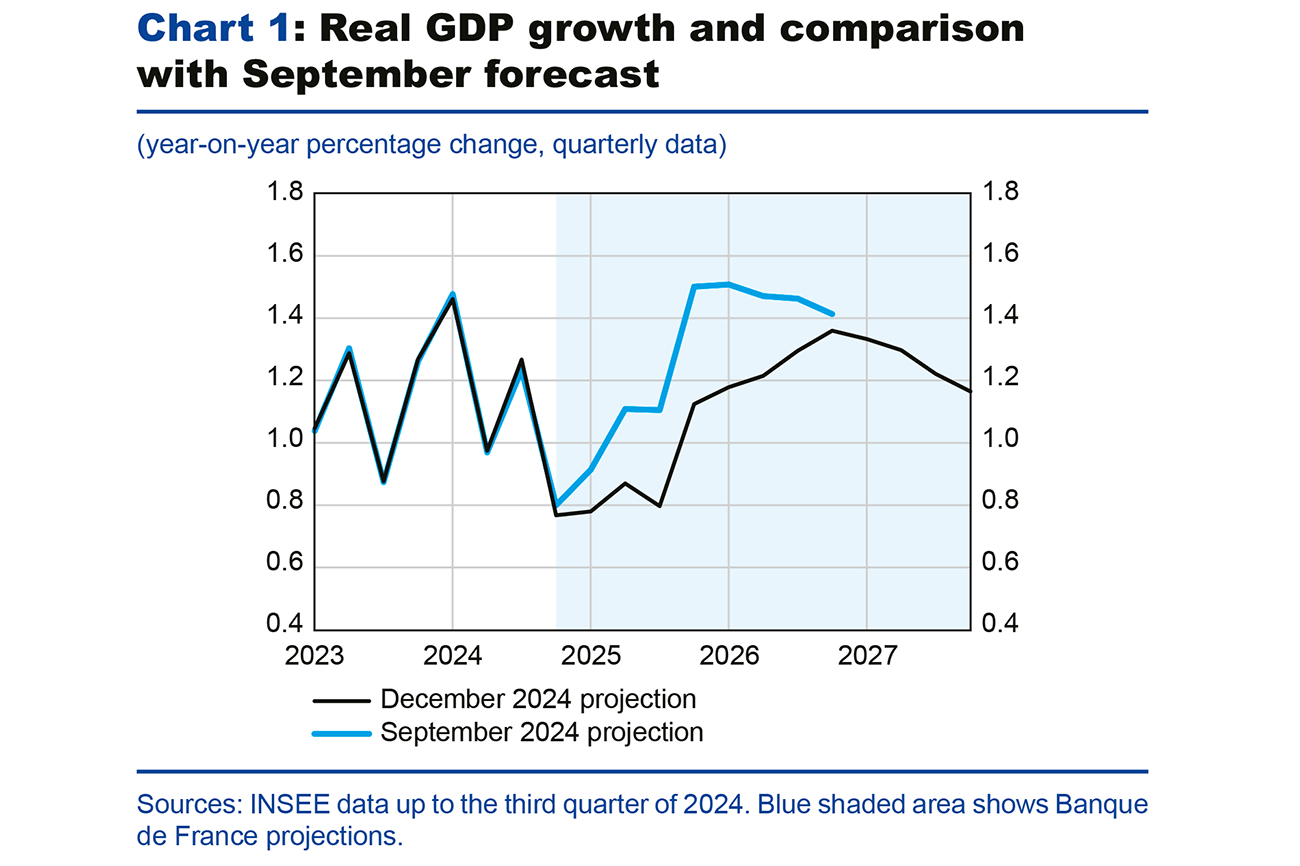

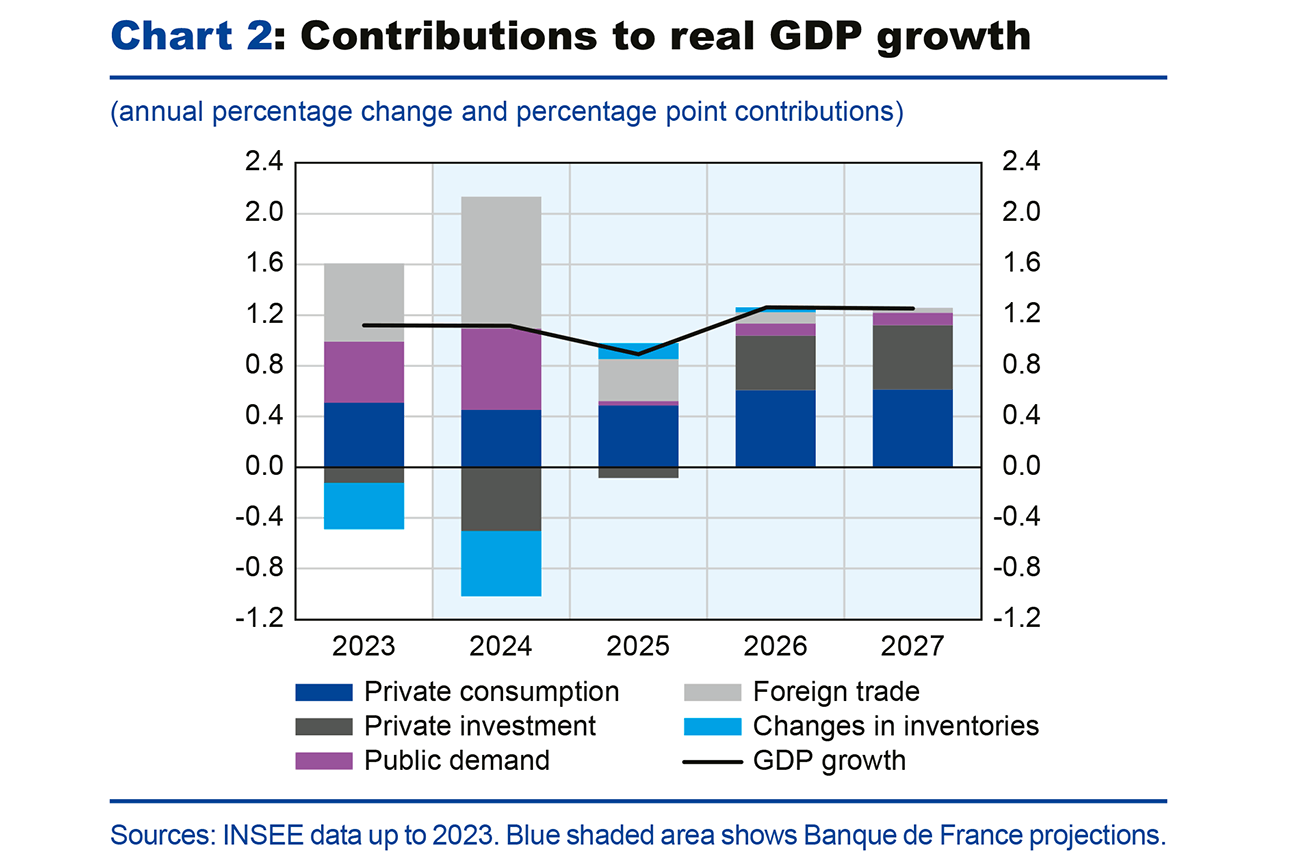

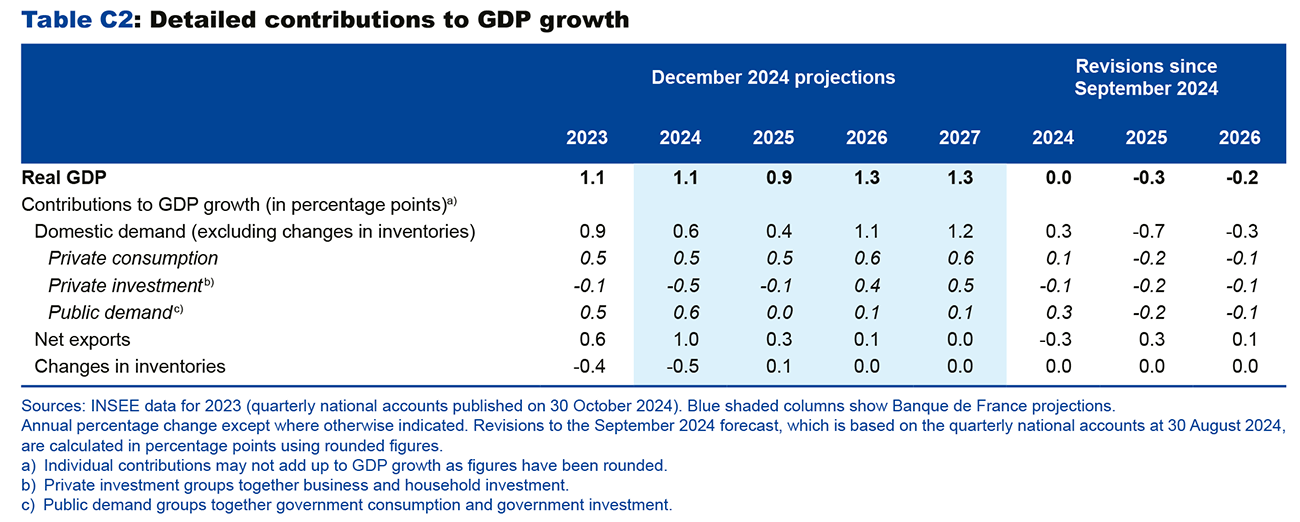

According to the results of the Banque de France’s latest Monthly Business Survey, drawn up at the beginning of December, activity is expected to be stable in the fourth quarter, due to the negative after-effects of the Olympic and Paralympic games on activity following their positive impact on growth in the third quarter of 2024. Growth is therefore expected to reach 1.1% for the year as a whole. Growth should be driven primarily by foreign trade (see Chart 2), but held back by destocking. Despite gains in the purchasing power of wages, consumption is expected to grow moderately in 2024, hampered by a saving ratio still almost 3 percentage points above its pre-Covid level. Business and household investment is expected to weigh negatively on activity, under the delayed effect of the past deterioration in financial conditions, against a backdrop of uncertainty that reinforces the wait-and-see attitude of private agents.

In 2025, the French economy is expected to continue to grow at a moderately low rate of around a quarter of a percentage point per quarter, or an annual average of 0.9%. Domestic demand is likely to be impacted not only by fiscal consolidation measures, but also by the uncertainty surrounding them. As a result, household consumption is likely to grow only moderately, after posting sluggish growth in 2024. The contribution of private investment should remain negative, but much less so than in 2024. The contribution of foreign trade to growth should still be positive, but less than in 2024 due to a normalisation of imports after a period of marked decline.

In 2026, annual growth is expected to rebound to 1.3%, spurred on by the easing of financial conditions. This easing should enable private investment to contribute positively to growth once again. Household consumption is expected to grow at a more sustained pace than in 2025, boosted by a slightly sharper decline in the saving ratio. In 2027, annual growth should be close to that of 2026, but the quarterly growth rate should normalise over the course of the year to approach the rate of potential growth, with year-on-year GDP growth reaching 1.2% at the end of 2027, compared with 1.4% at the end of 2026.

Compared with our September 2024 projection, economic recovery would be delayed from 2025 to 2026 (see Chart 1). GDP growth is unchanged for 2024, but weaker in 2025 and 2026.

Headline inflation should remain below 2% for a lasting period, whereas inflation excluding energy and food is expected to decline more gradually

According to Eurostat’s provisional estimate for November 2024, HICP inflation should reach 1.7% year-on-year, up from 1.6% in October 2024. Core inflation (excluding energy and food) is expected to come in at 2.2% year-on-year in November 2024, after reaching 2.1% in October 2024. The Olympic and Paralympic Games had an upward effect on inflation in certain services sub-sectors. However, this effect remained transitory and concentrated mainly in August 2024, and did not call into question the overall downward trend in inflation. Nevertheless, inflation should rise slightly and temporarily over the rest of the year, due to base effects on energy and services prices.

For 2024 as a whole, headline inflation is thus expected to drop sharply, from 3.0% year-on-year in the first quarter to 1.9% in the fourth quarter. This decrease should essentially be attributable to the downward trend in food and energy prices. Core inflation is expected to be more persistent, still standing at 2.3% in the last quarter of 2024 (compared with 2.5% in the first quarter of 2024). Services inflation is likely to decline more gradually. Prices of industrial goods could also strengthen towards the end of the year, due to geopolitical tensions in the Red Sea and higher sea freight rates. Compared with our September 2024 interim projections, headline inflation has been revised downwards due to lower oil prices than anticipated by the futures markets, and to downward surprises in services and manufactured goods inflation, especially a sharp drop in the price of communication services.

In 2025, inflation is expected to fall back again to an annual average of 1.6%, after averaging 2.4% in 2024. This decline is due in particular to negative inflation in energy prices (regulated electricity tariffs cut at the start of the year, price of a barrel of oil at EUR 68 according to technical assumptions derived from futures markets, compared with EUR 76 in 2024). This projection factors in the fiscal and social measures initially provided for in the draft budget acts, including the increase in domestic tax on final electricity consumption to above its level prior to the introduction of the energy price shield, and the increases in the contribution from private investors and the tax on airline tickets. If these measures were not applied (in particular, if the domestic tax on final electricity consumption did not increase above its level prior to the introduction of the energy price shield), inflation in 2025 would be around 0.2 point lower than in our projection. Inflation excluding energy and food is expected to continue to fall to 2.2%, after 2.4% in 2024, as a result of the gradual decline in services inflation throughout the year due to the normalisation of wage growth.

In 2026, headline inflation and inflation excluding energy and food are expected to reach 1.7% and 1.9% respectively, with no revision to our September 2024 interim projections. The slight rise in inflation in 2026 would be due to a smaller fall in energy prices and a slightly higher rise in food prices, in line with our technical assumptions for food commodities, while inflation excluding energy and food should continue to decline slowly. Finally, in 2027, headline inflation should come in at 1.9%, and inflation excluding energy and food at 1.8%. Services inflation should continue to slow throughout the year. Conversely, energy prices are likely to accelerate temporarily as a result of the extension of the CO2 emission permit market to other emitting sectors. Its impact on inflation – still uncertain – will depend on how it is implemented, and could be limited by compensatory measures.

Nominal wage increases above inflation

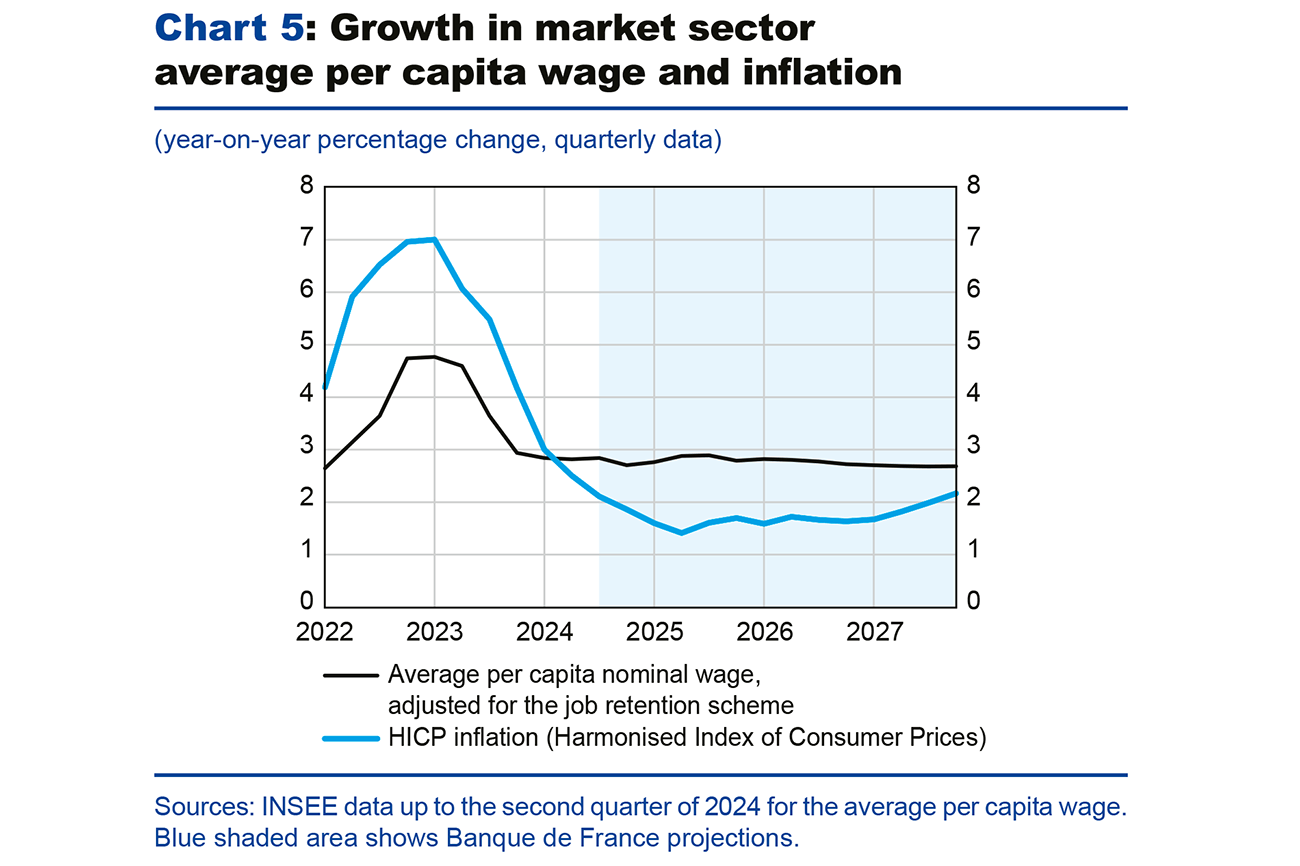

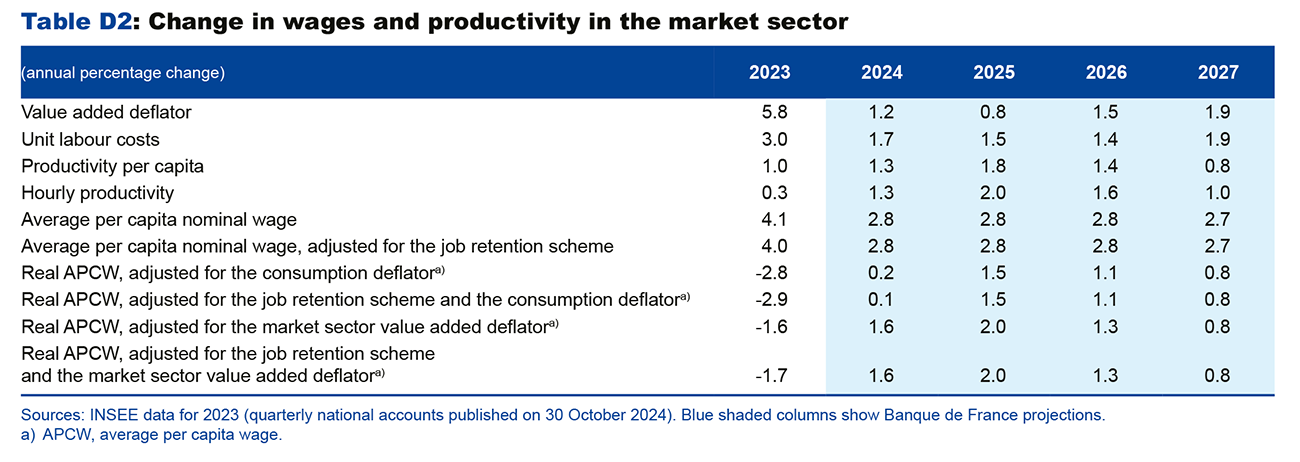

The growth rate of the monthly base wage, which excludes bonuses and overtime, declined as a result of less frequent upward revisions of the national minimum wage and lower negotiated wage increases under industry and firm-level agreements. Thus, according to the Banque de France indicator, based on pay scale increases in over 350 industries, negotiated wages are expected to rise by 2.7% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2024, compared with 4.8% a year earlier. Moreover, payments of the prime de partage de la valeur (PPV – value-sharing bonus) also fell, so that the rise in average per capita wages from the end of 2023 to mid-2024 was lower than that of the monthly base wage.

Average per capita wages thus began to slow in the market sectors from the second half of 2023 onwards. However, per capita wages have been rising faster than prices since the second quarter of 2024, a trend that is set to continue in the projection (see Chart 5). Compared with our September projections, the stronger-than-expected fall in inflation in the second half of 2024 has led to an upward revision of real wage growth for the current year. In 2025-2026, nominal wage growth is expected to remain sustained despite the decrease in inflation, thanks to productivity gains attributable to the partial absorption of temporary productivity losses observed in relation to the pre-Covid trend. However, real wages have been revised downwards over these two years compared with our September projection, in a context of a delayed recovery and a sharper rise in the unemployment rate. By 2027, nominal wage growth should converge towards a year-on-year increase of close to 2.7%, in line with inflation and productivity gains forecasts.

The unemployment rate is expected to rise temporarily in 2025 and in 2026, before dropping again

in 2027

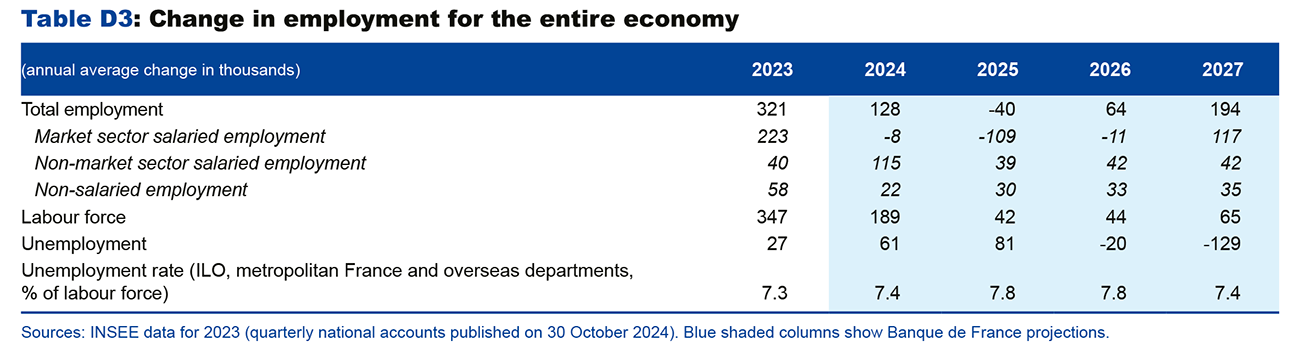

According to the latest economic indicators, the labour market is showing signs of softening, after having been surprisingly buoyant since the pandemic (1.1 million net salaried job creations since the end of 2019). INSEE’s latest estimate of salaried employment shows only a slight increase of 27,000 jobs in private sector salaried employment at end-September, following a decline of 32,900 jobs in the previous quarter. Business surveys also highlight a less dynamic employment situation. According to our projections, total employment should fall from the fourth quarter of 2024 through early 2026, reflecting a delayed impact from the slowdown in activity and the partial recovery of productivity losses observed since the Covid crisis. Market sector productivity has declined considerably compared with pre-Covid levels (see Devulder et al., 2024, Banque de France Bulletin). Over the projection horizon, the gradual end of labour hoarding phenomena witnessed in certain sectors, such as transport equipment, should drive a recovery in productivity gains. However, as most of the productivity losses can be explained by more lasting factors (past increases in apprenticeship contracts and other labour composition effects), this catch-up should only be partial. Our September projections for employment have been revised downwards, mainly due to a slowdown in market sectors.

Our employment projection factors in measures to reduce the apprenticeship bonus and the reduction in social security contribution exemptions provided for in the initial draft Budget Act. In the absence of these measures, employment could be more dynamic than in our baseline scenario over the entire projection horizon.

In view of the new employment trajectories we have factored in, the unemployment rate has been revised upwards on our September forecast (see Chart 6). It should reach an annual average of 7.8% in 2025 and 2026, before falling back to 7.4% in 2027, due to a steadier recovery in activity and a productivity cycle that will have closed by this time, thereby ceasing to weigh on employment.

From 2025 onwards, household consumption should once again become the main driver of growth,

on the back of purchasing power gains from wages

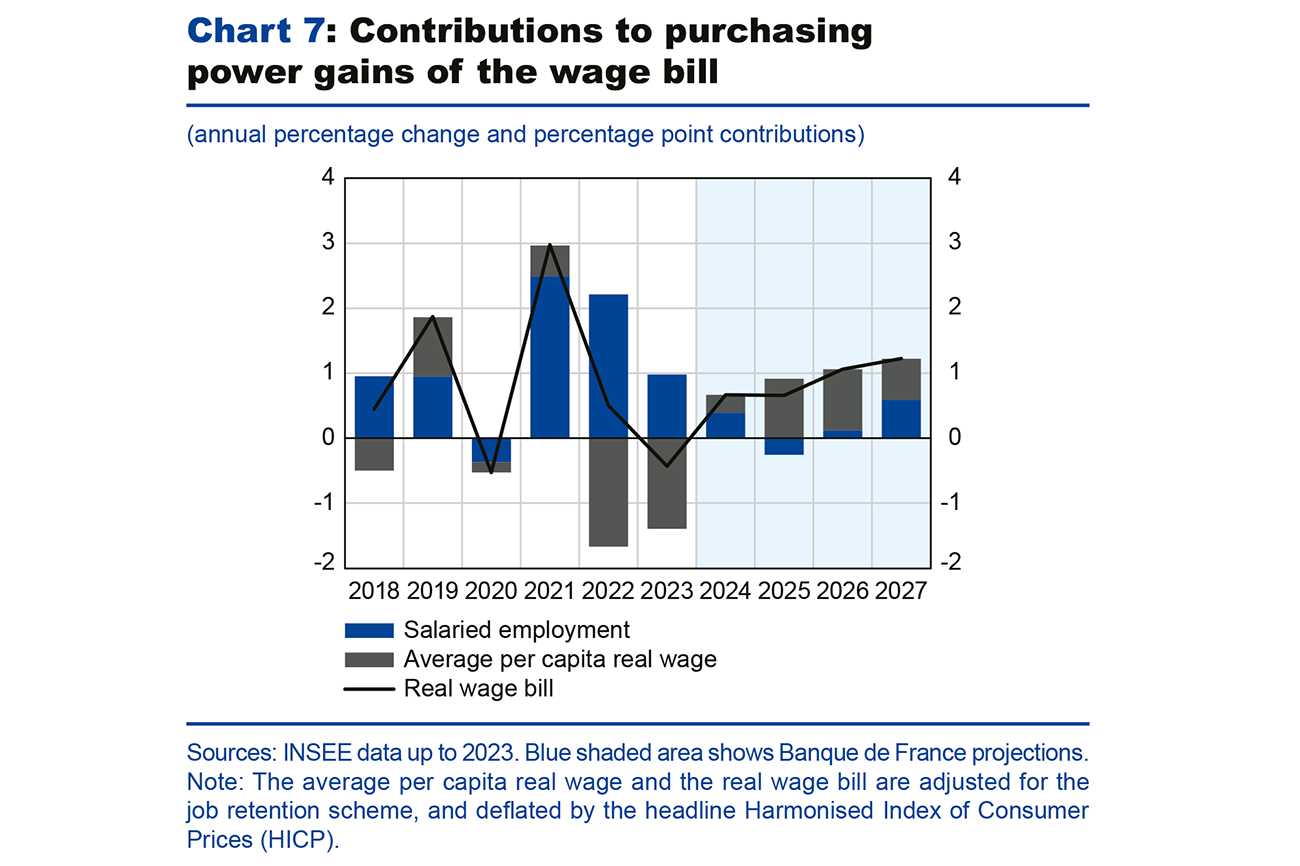

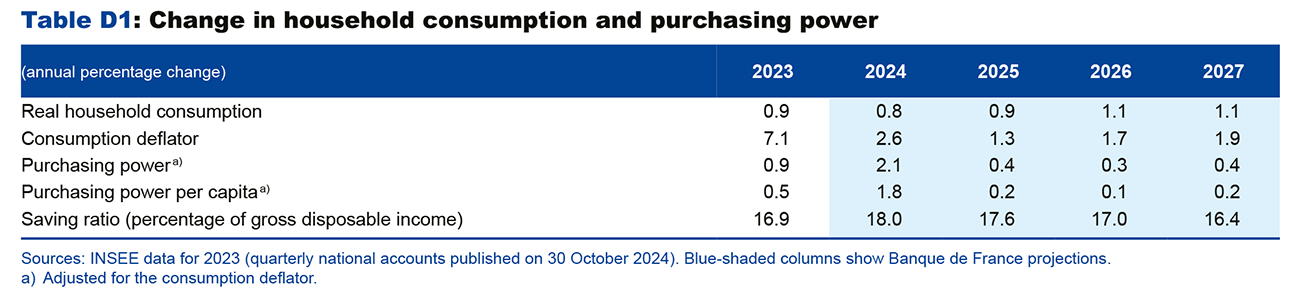

Based on our projections for inflation, per capita wages and employment, the purchasing power of wages should grow steadily over our projection horizon. However, its composition is likely to change (see Chart 7). In 2024, it is expected to rise by 0.7%, on the back of increases in both salaried employment and real per capita wages. In 2025, it should grow at a slightly higher rate of 0.9%, due to the acceleration in real wages and despite a slowdown in employment. It should then ramp up in 2026 and 2027 thanks to the recovery in employment driven by higher economic activity.

In the short term, the growth in household consumption should remain fairly limited, rising by 0.8% in 2024 and 0.9% in 2025. It should then regain some momentum in the medium term, with growth of 1.1% in both 2026 and 2027, thanks to the higher purchasing power of wages, provided that the current uncertainty is lifted and no longer encourages precautionary saving behaviour.

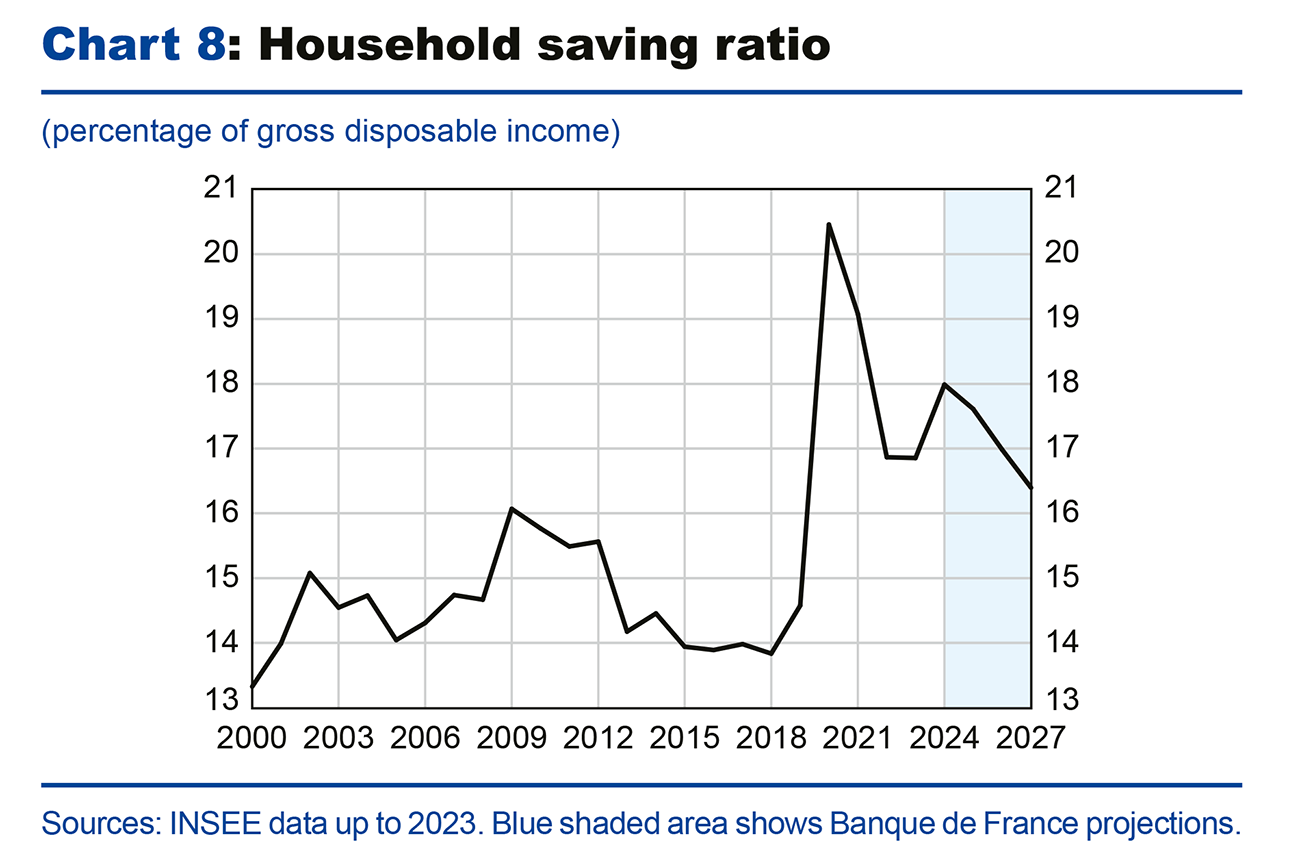

In response to this recovery in consumption, the saving ratio should begin to fall. However, in 2027 it is expected to remain above its pre-Covid historical average (see Chart 8). This decline in the saving ratio over the projection horizon is partly attributable to a reversal of the trend of recent quarters, when financial income contributed significantly to the growth of household income due to the increase in net interest income. Because financial income is more likely to be saved, this pushed up the household saving ratio in 2023-2024 (see Box 1). Conversely, the expected decline in interest income, combined with the increased purchasing power of wages, should lead to a fall in the saving ratio from 2025 on.

Household investment contracted sharply in 2023 and is likely to continue declining in 2024. Nevertheless, several indicators signal a recovery. First, household purchasing power has recovered slightly thanks to the easing of interest rates and property prices. Second, loans to households have picked up since April 2024, signaling a resumption of transactions in existing properties and a recovery in household investment in property-related services, although the recovery is still being hampered by a wait-and-see attitude in the market. Lastly, the number of building permits being issued appears to have stabilised after a long period of decline. Provided this momentum continues and feeds through to housing starts, the recovery in new housing should begin around mid-2025. Household investment should then pick up more sharply in 2026 and in 2027, once easier monetary and financial conditions have taken effect and household real estate purchasing power has recovered sufficiently.

Business investment is likely to continue to stagnate until 2025, before picking up in 2026-2027

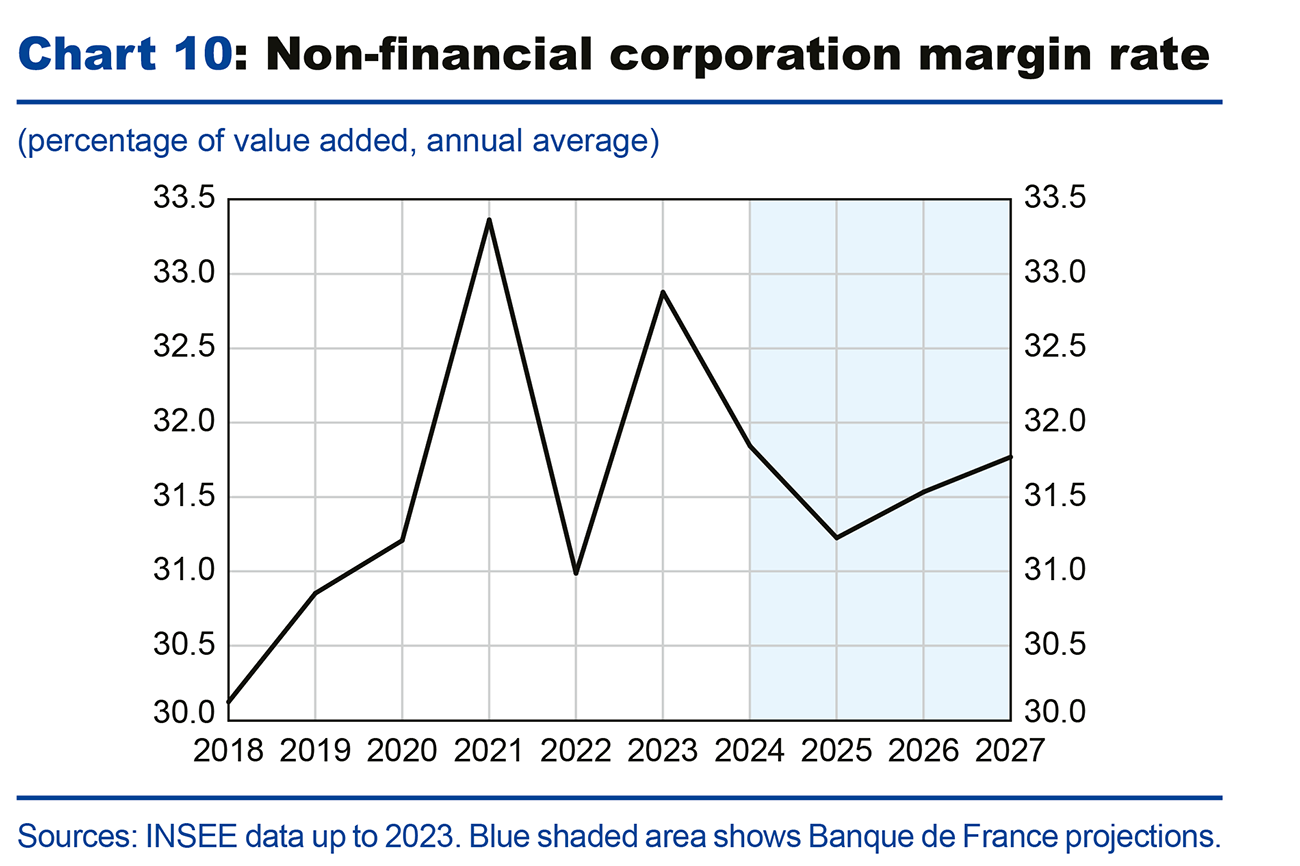

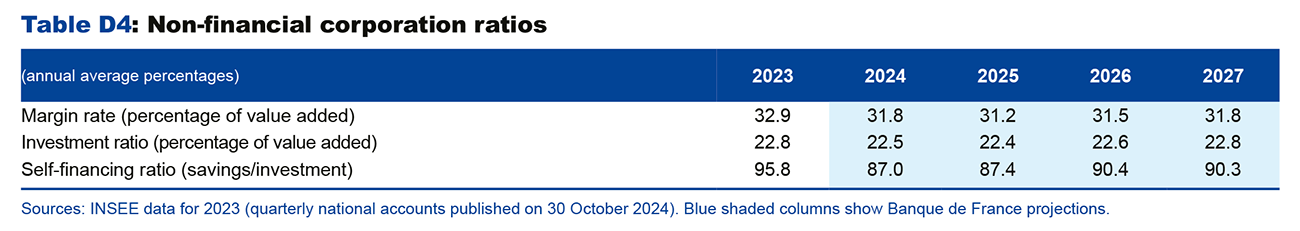

In 2024, business investment is expected to be penalised by financing costs and lending conditions (see Chart 9). However, interest rates charged to businesses have begun to come down, and the latest bank lending survey shows that the supply of credit is improving and demand is picking up. Growth in business investment is likely to remain sluggish overall until the end of 2025, due to fiscal and budgetary uncertainty. It should regain momentum over the next two years, driven by current investment requirements in the digital and energy transitions, as borne out by the recent confirmation of projects to build electric battery “gigafactories”. The recovery in investment is also likely to be underpinned by the recovery in business activity and by companies maintaining their margins at a relatively high level.

After peaking at 32.4% in the third quarter of 2024, thanks to the contributions of the energy and transport services sectors to market sector growth, the margin rate of non-financial corporations is expected to decline towards the end of the year. Thereafter, the recovery in productivity gains associated with the slowdown in wages should restore margins through to the end of our projection horizon (see Chart 10). Nevertheless, it should be noted that the margin rate indicator only partially describes the financial situation of companies.

By working assumption, the 2025 deficit could be between 5% and 5½% of GDP, after a deficit of 6.1% in 2024

In 2024, the government budget deficit is projected to decline to 6.1% of GDP, following the 5.5% deficit recorded for 2023. This fresh deterioration in the fiscal situation would result from taxes and social security contributions lagging behind GDP growth, due in particular to the composition of growth (driven by exports and public consumption) and levels of primary spending (excluding tax credits) in excess of GDP growth, and a rise in interest payments in GDP points.

Our projections were finalised as at 27 November, using assumptions relating to public finances close to those of the draft Budget Act and the draft Social Security Financing Act for 2025 presented on 10 October, leading to a significant reduction in the government deficit to 5.0% of GDP in 2025 in our baseline scenario. As a result of the vote of no-confidence in the government held on 4 December 2024, this legislation will not be enacted. Under the alternative transition scenario, a special act would be voted by parliament authorising the State to continue collecting existing taxes until the new Budget Act for 2025 is enacted. This special act would also make it possible to disburse the budgets allocated to the different government departments, i.e. those that are essential to the execution of public services. The amounts allocated may not exceed the amount allocated under the initial Budget Act for the current fiscal year.

On the revenue side, the adoption of this special act would result in the cancellation of the social security measures provided for in the draft Budget Act (1 GDP point). However, freezing income tax brackets at 2024 levels would increase income tax revenue for 2025, adding around EUR 4 billion to government tax revenue. Overall, enactment of the special law would lead to a loss of revenue equivalent to slightly less than 1% of GDP when compared with our baseline scenario.

On the expenditure side, freezing the spending of central government departments at 2024 levels could lead to consolidation close to that forecast in our baseline scenario, despite the abandonment of the spending measures provided for in the draft Budget Act.

As a result, the enactment of the special act would lead to a significant upward revision of the government deficit in 2025. However, a new Budget Act for 2025 would have to be passed at some later date, incorporating updates to the assumptions relating to public finances and reducing this deficit ratio as much as possible. This is why we have assumed a deficit of between 5% and 5½%. This would not alter our growth scenario for 2025, insofar as the effect on demand of less fiscal tightening than provided for under the initial Budget Act would be offset by a smaller reduction in uncertainty concerning the outlook for the public finances.

Beyond 2025, the government budget balance will depend on the actual deficit recorded in 2025. The initial fiscal assumptions used a primary structural adjustment of 0.4 potential GDP points in 2026 and 2027, lower than that used in the medium-term structural programme (0.6 point in 2026 and 0.7 point in 2027), based on expenditure cuts for which few details have been provided, and they have therefore not been included in this projection. This adjustment could be revised upwards as a result of a smaller consolidation in 2025.

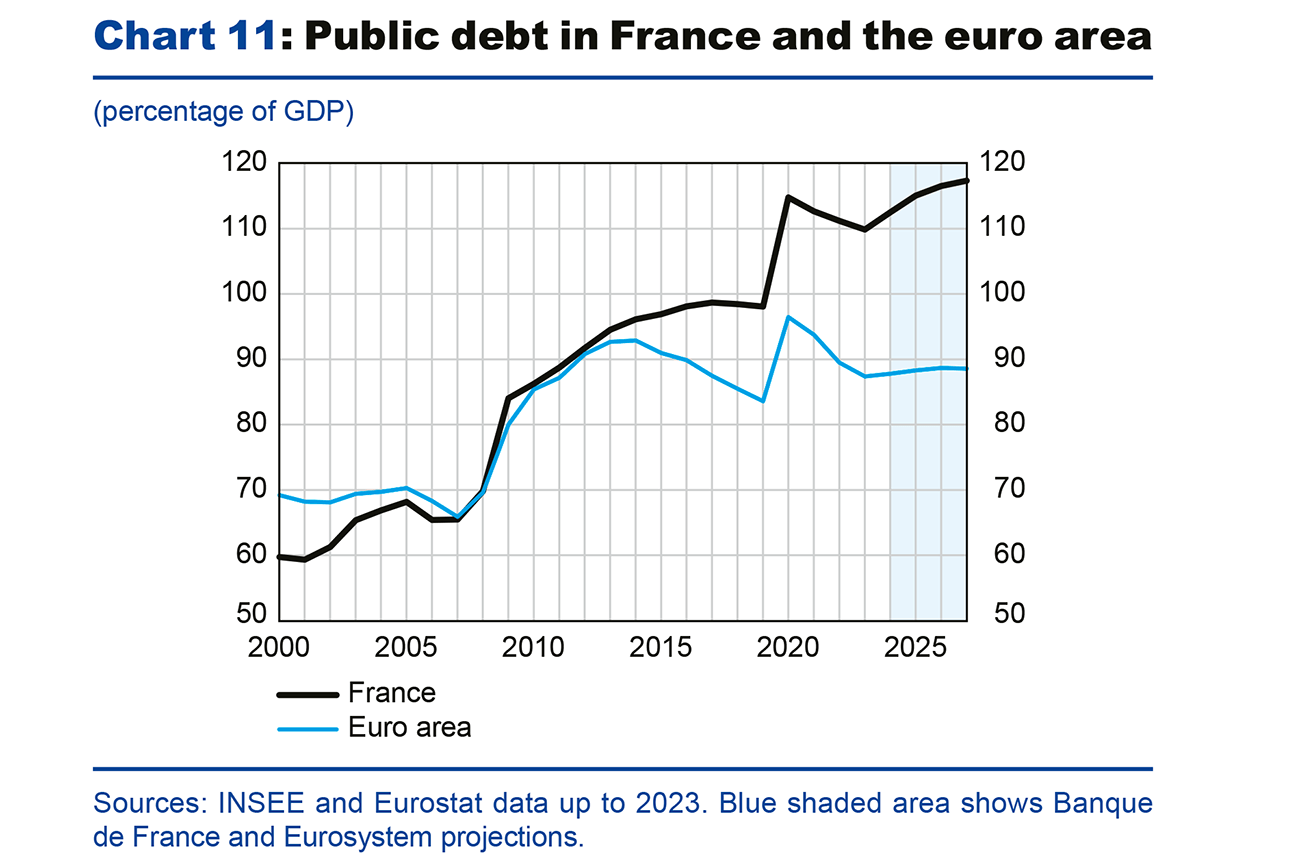

Under our baseline scenario, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to increase over the entire projection horizon to stand at 117 points in 2027 (see Chart 11). In comparison, the debt-to-GDP ratio for the Eurosystem would be 89 points in 2027. Fiscal consolidation is necessary to bring public debt under control. It should be remembered that, all other things being equal, it is the primary balance – excluding debt interest payments – that makes it possible to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio. For France, this primary balance would correspond to a total deficit reduced to 3% of GDP in 2029

Risks are generally on the downside compared with our growth projections and – to a lesser extent – with inflation

Even more so than in our previous projections, the national political – and therefore budgetary – context remains highly uncertain. As such, risks are to the downside in respect of French growth, with a risk that consumer and investor behaviour will be more wait-and-see. Inflation could be slightly lower than our forecast for 2025 if the increases in indirect taxes (domestic tax on final electricity consumption, tax on airline tickets) initially planned in the draft Budget Act are not reintroduced in a future Budget Act. In the longer term, a greater-than-expected softening in the labour market would weigh more heavily on wage increases and, ultimately, on inflation.

Domestic uncertainties are compounded by geopolitical risks. The war in Ukraine and the situations in the Middle East and the Red Sea are still hotbeds of instability that could exacerbate pressure on oil and gas prices and shipping costs, leading to an increased risk of both higher inflation and lower levels of activity. However, an increase in US oil and gas production could weigh on energy prices, resulting in a downside risk to inflation and an upside risk to economic activity. Lastly, still at international level, a sharp rise in customs duties in the United States, which could also lead to generalised trade tensions, would most likely have a negative impact on activity in Europe, and in France in particular. However, the effects on European and French inflation would be more mixed (see Box 2).

Boxes

The factors that have recently pushed up the household saving ratio should partially dissipate over our projection horizon

After reaching historically high levels in 2020 during the health crisis, the household saving ratio has come down but is still at a high level. At 18.2% in the third quarter of 2024, it remains around 3 percentage points above its pre-Covid level.

According to our analyses, two factors play a major role in explaining this higher saving ratio: changes in the composition of income and uncertainty.

The first factor is the change in the composition of household gross disposable income (GDI). Between 2019 and 2024, property income – including financial income – increased faster than household GDI (59%, compared with 26%), unlike income from employment and social benefits (both rose by 21%). However, financial income has a higher marginal propensity to be saved than average income, due in particular to its concentration at the top of the income scale (wealthier households have a higher marginal propensity to save). In addition, a given household may have a higher propensity to save its financial income than its earned income, in particular for life-cycle purposes (saving for retirement). Finally, over the recent period, households have undoubtedly saved a large proportion of their additional interest income, since this has merely offset the erosion effect of inflation on their net financial wealth. In addition, over the period under consideration, the fall in the weight of taxes and social security contributions relative to household GDI has also contributed to the rise in the saving ratio: cuts in tax and social security contributions tend to be saved more, as they concern a greater proportion of wealthier households.

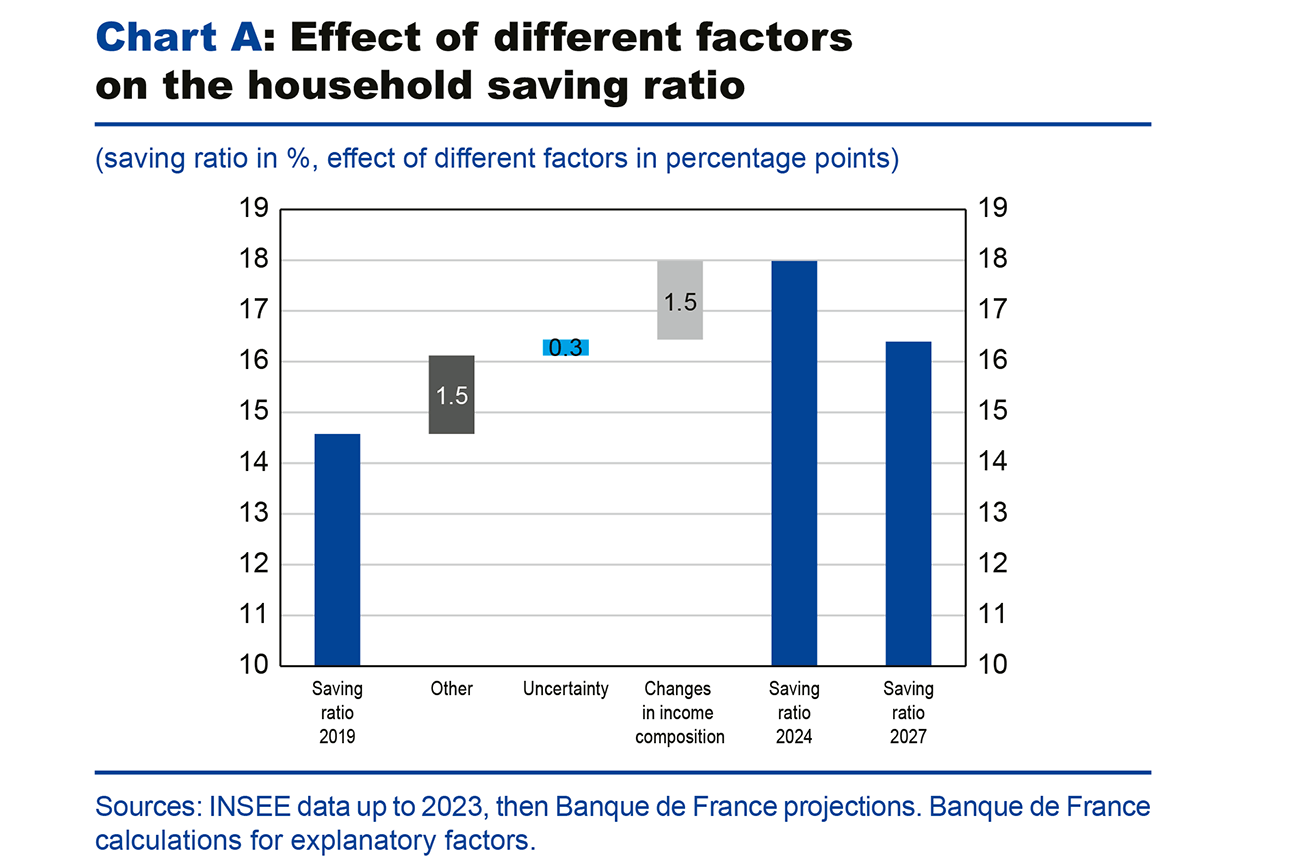

According to our estimates, changes in the composition of GDI accounted for half (1.5 percentage points) of the rise in the household saving ratio (see Chart A).

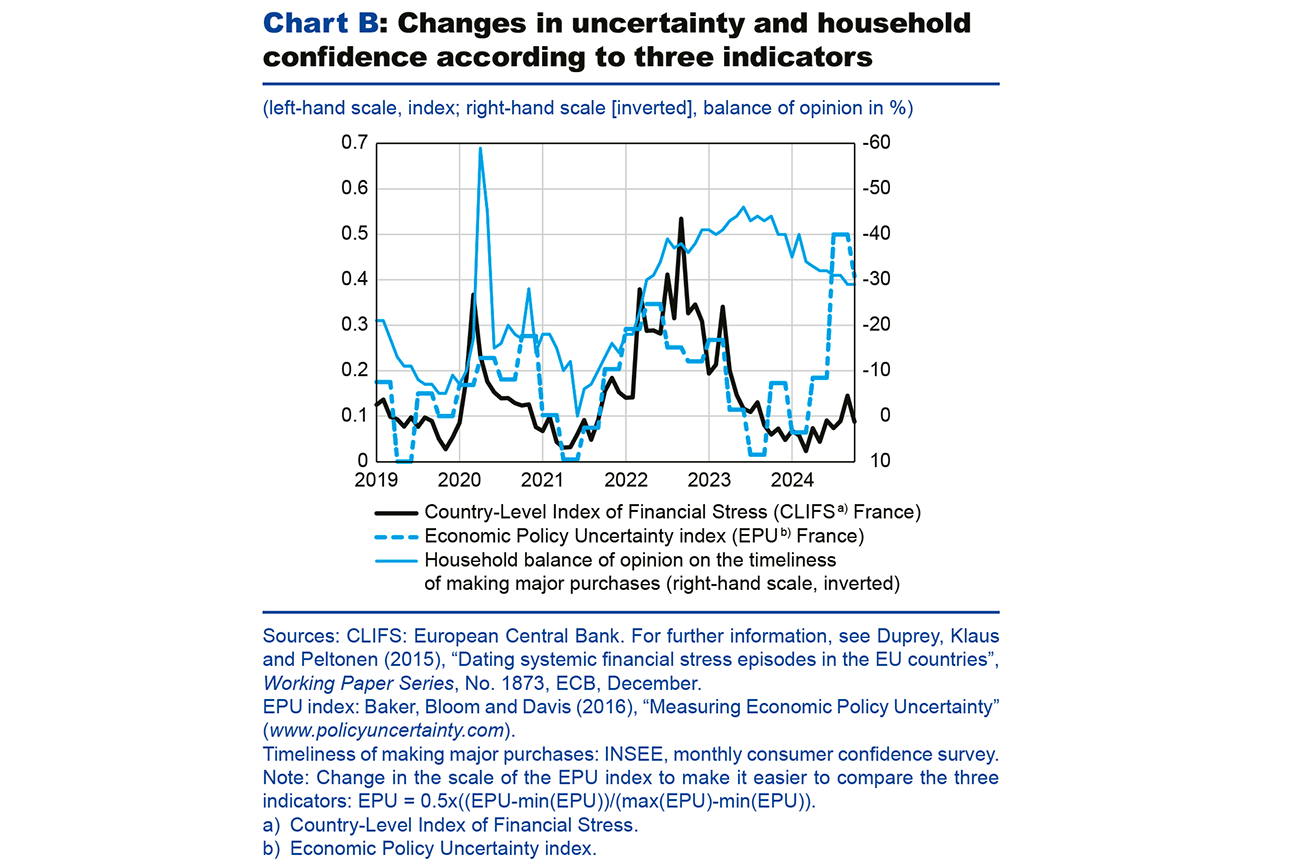

The second factor is the effect of uncertainty. This rose during the Covid crisis and has remained persistently high ever since, firstly because of the geopolitical context (war in Ukraine, tensions in the Middle East), and more recently because of the political situation in France (see Chart B). Households have thus been able to increase their precautionary savings to protect against future risks. According to our estimates, the impact of uncertainty on the saving ratio was greatest on two occasions (resulting in a temporary increase in the saving ratio of more than 1 percentage point), during the first lockdown in 2020 and then following the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian war. Between 2019 and 2024, it is estimated to have contributed around ½ percentage point to the rise in the saving ratio.

Overall, of the 3.3-percentage point rise in the saving ratio between 2019 and 2024, around 1.5 percentage points would be attributable to the composition effect and ½ percentage point to uncertainty (see Chart A). This would therefore leave the remaining 1.5 percentage point to be explained. Another possible explanation may be the past sharp rise in the household debt ratio. Indeed, rising mortgage repayments require higher levels of savings to stabilise the debt ratio, thus constituting a form of forced savings.

For the 2025-2027 period, we expect the share of financial income in household GDI to decline, due to lower short-term interest rates (in particular on interest-bearing deposits). Conversely, the share of income from wages should rise. As a result, the change in the composition of household income should push down the saving ratio over our projection horizon (by 1.6 percentage points to 16.4 % in 2027). By contrast, if it were to persist, the high level of uncertainty linked to the current political situation and longer-term budgetary prospects could delay or hamper this expected decline in the saving ratio.

The risk of trade tensions in the wake of the US elections is creating a downside risk

for activity in Europe and France, whose magnitude is difficult to quantify

The US election result in early November 2024 raises the risk of a fragmentation of international trade, which constitutes a significant factor of uncertainty for our projections. The risk of trade tensions introduces a threefold uncertainty into our scenario: i) uncertainty as to the outbreak of such tensions and to retaliatory measures; ii) the scale and scope of tariff hikes in the United States and the rest of the world if they were to occur; and iii) the potential effects of tariffs. This box takes a qualitative look at the channels and expected effects of a generalised increase in tariffs on economic activity and inflation in the euro area and in France.r

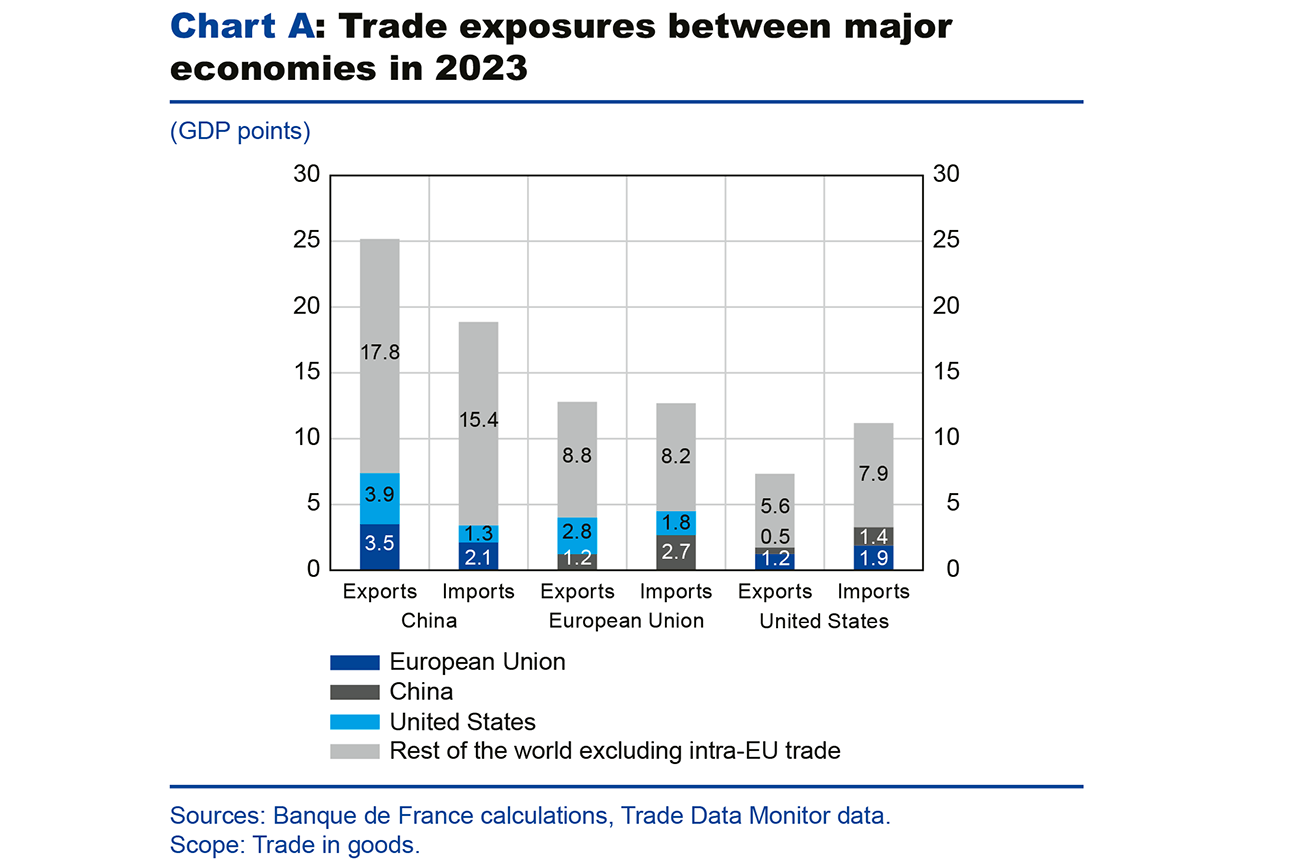

The European Union is very open vis-à-vis the rest of the world. In 2023, EU-27 exports of goods and services to third countries represented 22% of GDP, and imports from these same countries 20% of GDP. This compares with 12% and 15%, respectively, of GDP for the United States, and 20% and 18% of GDP for China.

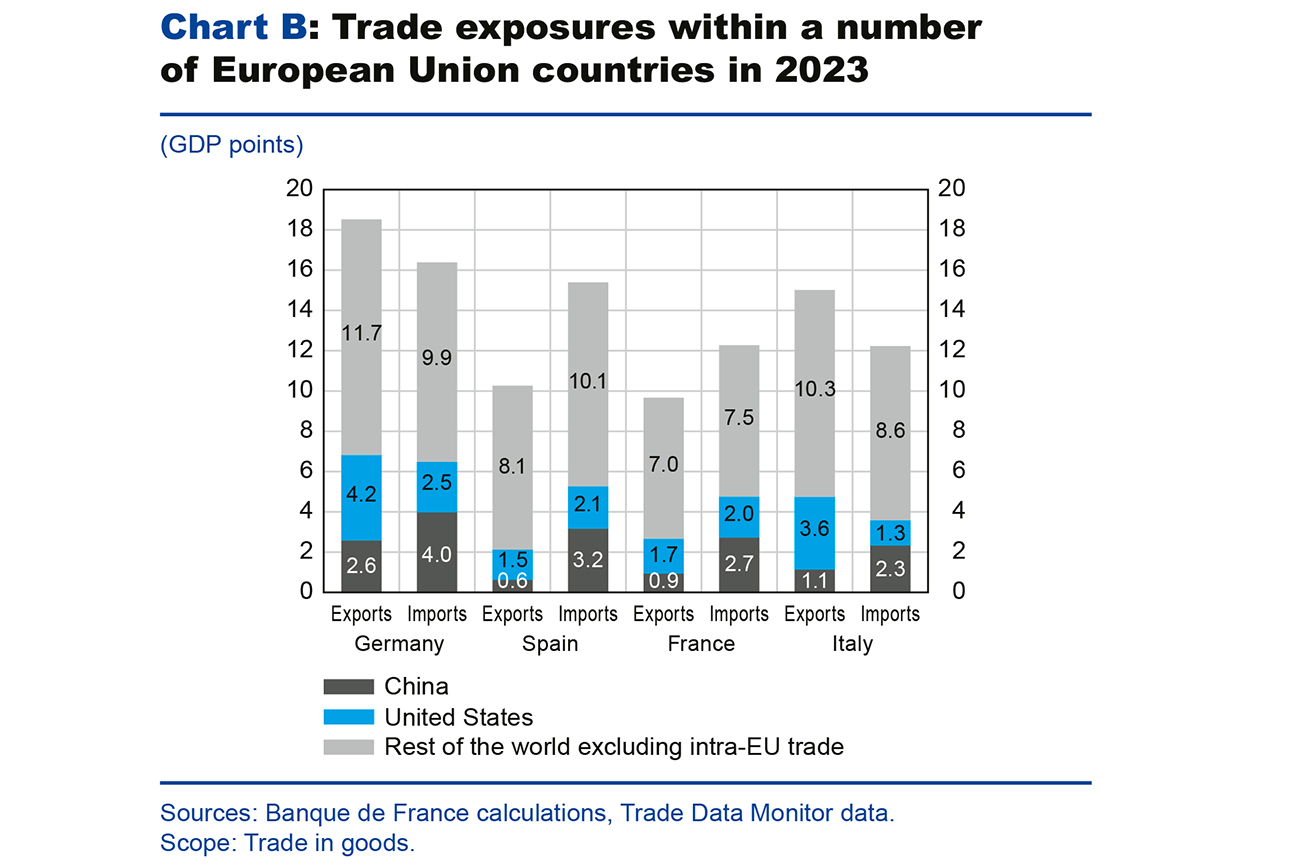

However, an exposure to the consequences of trade tensions needs to be assessed in terms of the geographic and sectoral scopes covered by the new customs measures. Although the nature and extent of the new trade restrictions, which could be announced in the course of 2025, remain uncertain, the risk for euro area activity mainly concerns trade in goods with the United States. In 2023, EU exports to the US market represented 2.8% of GDP for the EU-27, and imports from the United States 1.8% of GDP (see Chart A). Within the euro area, exporters’ exposure to the US market is above average for Germany (4.2% of GDP) and Italy (3.6% of GDP), and below average for France (1.7% of GDP) and Spain (1.5% of GDP) (see Chart B). At industry level, the euro area’s exposure is the highest for automobiles, machinery, aeronautics, pharmaceuticals, chemicals and food products.

In 2023, US exports of goods to the European Union represented 1.2% of GDP, and US imports from the European Union 1.9% of GDP. In comparison, US goods exports to and imports from China represented 0.5% and 1.4% of GDP respectively. Thanks to the sectoral composition of its exports, focused on services, intellectual products and energy, the United States is less exposed to the consequences of trade tensions targeting manufactured goods, compared with its partners, including EU countries

The expected effects of a rise in tariffs (increase in US customs duties and possible retaliatory measures by China and Europe) on activity in the euro area and France would occur through various channels, with various opposing effects.

On European exports:

- Higher US tariffs on imports from the euro area would directly reduce US demand for European goods. Lessons learned from trade tensions between the United States and China between 2017 and 2019 show that the reaction of import volumes to new tariffs is rather limited in the short term, with a so-called “unitary” elasticity after one year: a 10% increase in tariffs would lower the volume of US imports by an equivalent percentage. The size of this mechanism and its impact on activity depend on the share of the US market in European exports (see Chart B).

- If the United States were to raise its tariffs on Chinses goods more than on European goods, the negative impact on European producers could be slightly mitigated by the loss of competitiveness of Chinese goods on the US market (vis-à-vis their European competitors). Should China retaliate against the United States, US goods would also become less competitive on the Chinese market, which could indirectly benefit European exporters. However, such trade tensions could lead to China redirecting its exports towards the euro area market, thus competing with European producers, which could weigh on activity (and inflation) in the euro area.

Other mechanisms can also alter the consequences of trade tensions on activity and inflation, in particular:

- A depreciation of the euro against the US dollar would improve the price competitiveness of European exporters and boost activity in the euro area, but would also increase the price of imports (including on intermediate goods), particularly given the large share of imports that are invoiced in US dollars. In France, for example, around 60% of extra-EU imports are invoiced in US dollars.

- A rise in uncertainty surrounding these various tariff measures (target countries, scale, implementation timeline, possible retaliation) would have a negative impact on activity in the euro area, due in particular to the effect on investment of a more wait-and-see attitude on the part of European exporters. However, this uncertainty could rapidly be lifted as the new US administration clarifies its trade policy.

Overall, the risks posed by these various effects on French growth appear to be rather negative, although they are smaller than in the euro area due to the lower exposure of French exporters to the US market. However, they are very difficult to quantify precisely owing to the threefold uncertainty that characterises them. It is harder to anticipate the sign of the total impact on inflation of these different shocks (extra- and intra-euro area competitiveness, reallocation of Chinese products to the European market, exchange rate), which also depend on the reactions of the European Union and China to an increase in US tariffs. As a result, the risks to inflation in France appear relatively mixed, on both the upside and the downside.

Appendix

Download the full publication

Updated on the 3rd of January 2025