Give the central bank a clear mandate of price stability. Grant it full independence from the government. And appoint at its head a steadfast governor who will not let anything but its mandate influence its policy. Does the central bank then have all it needs to deliver price stability? Or must requirements on the government's fiscal policy also be imposed? The question is a cornerstone of monetary-fiscal interactions, determining whether monetary policy has the power to insulate inflation from imprudent fiscal decisions, or is ultimately dependent on a well-behaved fiscal authority.

The existence of fiscal requirements for price stability is at the root of the convergence criteria of the Stability and Growth Pact in the euro area, but they have no consensual basis in economic theory. Today, the main rationale for fiscal requirements is stipulated by Leeper (1991), Sims (1994), Woodford (2001), and the subsequent Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL): for the central bank to be able to deliver price stability, the real value of public debt at stable prices must be equal to the net present value (NPV) of future real fiscal surpluses.

Yet the NPV requirement has remained controversial to this day. In particular, recent skepticism points out that it is derived under the strong assumption of Ricardian households, when finite lives, financial frictions, or limited foresight are enough to make households non Ricardian. Whether fiscal policy can make monetary policy lose control over inflation when households are not Ricardian is heavily debated.

In this paper, we show that when households are not Ricardian, fiscal requirements for price stability do exist, but that they reduce to the very different form of a limit on the real-debt-to-GDP ratio. When the debt-to-GDP ratio is above the threshold or projected to grow above this threshold in the future, no stable price equilibrium exists. The debt-to-GDP limit arises because above it, no interest rate however high can counter-balance the effect of higher debt on aggregate demand and bring it back in line with aggregate supply. To restore an equilibrium, inflation must necessarily set in to erode the real value of public debt, lowering households’ real wealth and therefore aggregate demand.

We derive the debt-to-GDP requirement in two steps. First, following the derivation of the NPV requirement when households are Ricardian, we consider what requirements arise from households’ intertemporal budget constraints. We show that when households are not Ricardian, households' intertemporal budget constraints impose only very weak requirements. In particular, if, from any current level of public debt, the government plans on never raising any tax to repay it, this violates no household's intertemporal budget constraint.

Second, we show that a new requirement arises when households are not Ricardian. Higher public debt increases aggregate demand through a wealth effect, and puts upward pressure on inflation. This in itself poses no constraint on the ability of the central bank to maintain price stability. The central bank can counter the inflationary effect of higher debt with higher interest rates, just like it can counter any other inflationary shock with higher interest rates, retaining the ultimate control over inflation. Yet we show that there exists a threshold on the debt-to-GDP ratio above which even infinitely high interest rates are not enough to counter the wealth effect of public debt, resulting in the limit on the debt-to-GDP ratio.

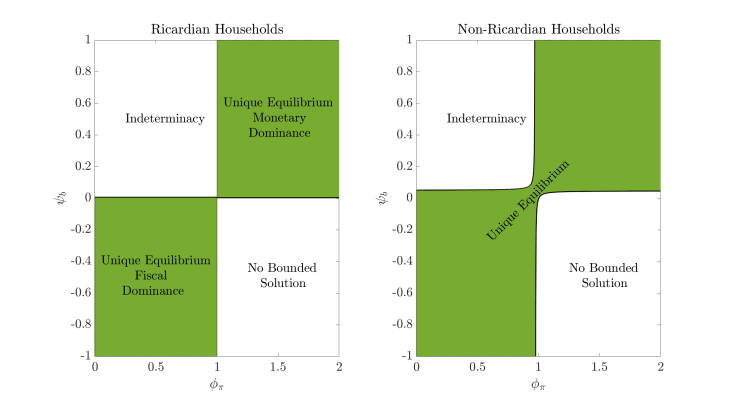

We conclude by analyzing how the central bank can implement price stability once these fiscal requirements are satisfied. In doing so we reconsider Leeper (1991)’s local version of the FTPL in the case of non-Ricardian households. We show that when the central bank follows a standard Taylor rule that responds to inflation, fiscal shocks always affect inflation, however strong the response of monetary policy to inflation. It it no longer possible to distinguish between a monetary regime and a fiscal regime (see Figure below). Yet, we show that monetary policy can implement price stability if, on top of reacting to inflation, it directly responds to the level of public debt—not just to the higher inflation that higher debt generates.

Keywords: Monetary-Fiscal Interactions, Non-Ricardian Households, Price Stability

JEL classification: E52, E62