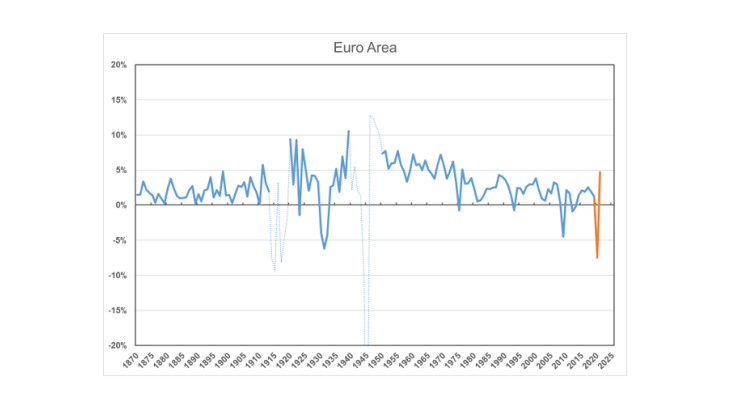

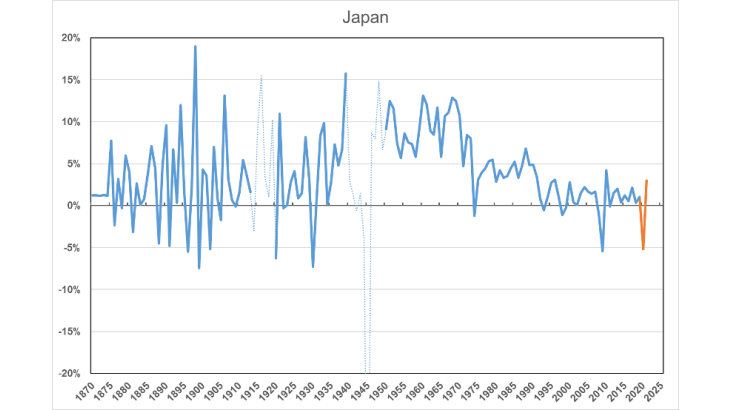

The financial crisis of 2008-2009 seemed so far to be the second significant episode of GDP contraction in modern history and was thus called the "Great Recession". However, the magnitude of the current contraction in GDP is expected to be much larger. As such, the Covid-19 recession is expected to become, in terms of its impact on growth, the deepest for a considerable length of time, after of course the Great Depression.

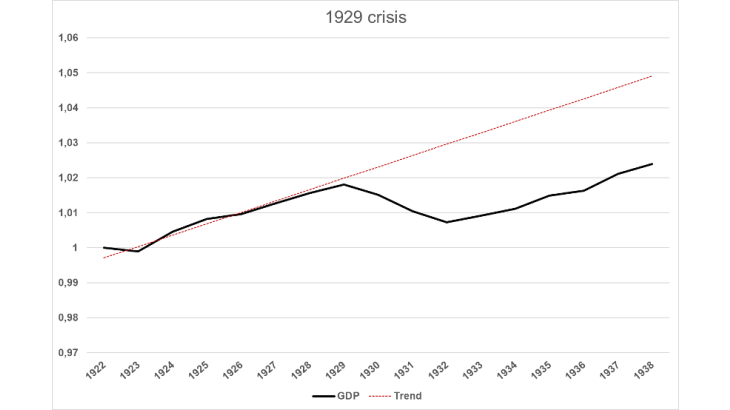

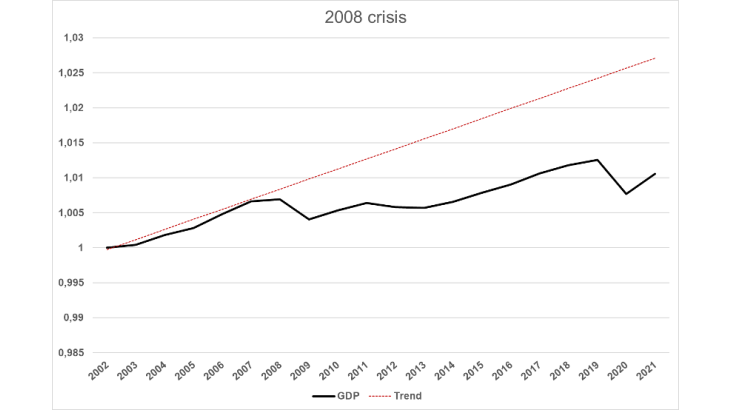

There could, nonetheless, be a significant difference. The Great Depression, which was also a financial crisis, was followed by a catch-up process that took several years, despite the highly favourable technological context (Gordon, 2000). In the United States, the 1929 level was reached again in 1936, for the euro area in 1937 (Chart 2); growth returned to the pre-crisis trend after a few years (before the break due to the Second World War for the euro area), but remained very far from its trend level. The financial crisis of the late 2000s was followed by a slower return to growth than in the previous period, with no immediate significant recovery of GDP losses. In this respect, many studies show that financial crises have very lasting effects on GDP (Reinhard and Rogoff, 2009). This is notably because the period leading up to the financial crises is characterised by an unsustainable growth trend, for example since it is based on a continuous growth in debt ratios that boost demand.

A faster rebound than after the 1929 and 2008 crises?

The path out of the Covid-19 crisis will largely depend on health policies aimed at protecting populations, which may influence the strength of both supply and demand. It will subsequently depend on the state of the production base at the end of the crisis and on effective workforce dynamics as well as productivity dynamics.

As regards the production base, all countries have implemented monetary and fiscal policies on a scale unprecedented in history in order to reduce the risks of capital destruction resulting from business failures (see, in particular, the IMF’s policy tracker). It is true that investment is expected to be temporarily depressed during the crisis, but economic recovery should be greatly facilitated by keeping the production base in operation.

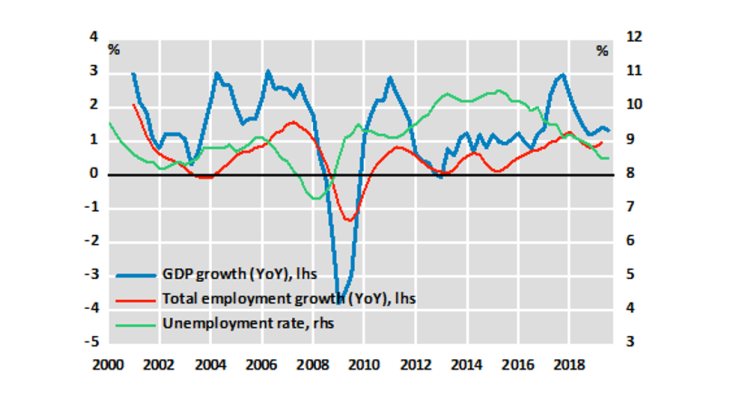

As regards the workforce, the responses differ greatly across countries, and are contingent on their different institutional contexts. Some, such as the United States, leave market forces to play a major role, with large numbers of dismissals and a surge in unemployment registrations, exposing these workers to economic risks as well as to loss of human capital for firms, but facilitating the reallocation of labour when the recovery takes hold. Others, such as France, have introduced powerful, albeit costly, protective measures such as short-time work, which make it easier to keep workers in companies and thus reduce the risk of losing human capital.

Lastly, the Covid-19 crisis started at a time when, outside periods of war, productivity growth rates were historically low in all countries. It is quite conceivable that these rates will remain low in the aftermath of the crisis and that they will be even more affected by an uncertain international environment for several years to come. From this point of view, the measures taken by multilateral institutions to stabilise developing countries (debt moratorium, IMF loans, etc.) or cooperation between countries to mitigate financial tensions (in particular swaps between central banks in dollars) could help to reduce the uncertainty shock caused by this crisis.

The scenario based on the deployment of the digital economy

For all that, another more favourable scenario is conceivable: that of an acceleration in productivity resulting from a positive shock from the use of digital technology that has supported health policies and, in particular, lockdown periods. This would imply a real, widespread transition into the digital work era. This is reflected, for example, in the massive increase in teleworking, i.e. almost 40% of jobs in France according to DARES, and an estimated 34% in the United States according to Dingel and Neiman (2020). These forms of work save time (transport in particular) and constitute a major shift in firms' demand for commercial real estate. The associated productivity gains would primarily concern the service sector, which now accounts for the lion's share of the economy.

According to Bart van Ark (2016), the digital economy is still in its "installation phase" and is yet to enter its "deployment phase". The Covid-19 crisis may facilitate this rapid transition to this "deployment phase" of the digital economy, associated with significant productivity gains conducive to a return to stronger growth. This would help to pay off the debt burden that has been skyrocketing due to the support and protection policies implemented during the crisis.