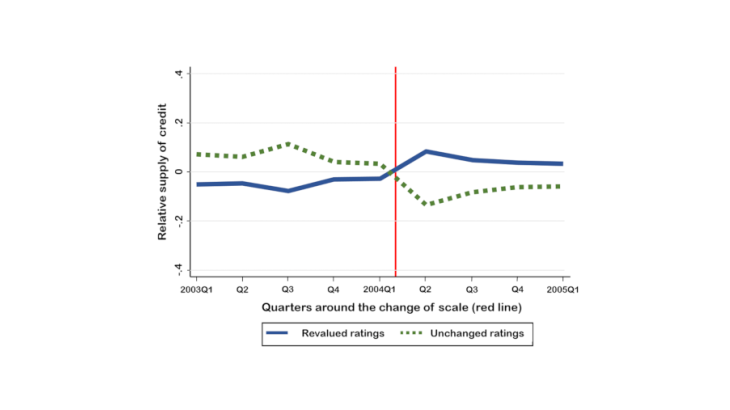

Source: Cahn, Girotti and Salvadè, 2018

Note: The relative supply of credit is measured by the quarterly change in outstanding loans as a % of the total assets, adjusted for differences related, amongst others, to the sector, the period and the companies’ unobservable characteristics.

In credit operations, the issue of information asymmetry is a major concern. The custodian of funds must ensure that the user will be able to guarantee repayment, while the former only partially controls the use of these funds. Benefiting from a de jure quasi-exclusive monopoly of credit operations, banks have developed risk monitoring and supervision techniques that characterise their activity.

Credit risk analysis is based on the use of a set of information, schematically broken down into two categories: (i) the verifiable information, most often drawn from financial statements, from which the bank may predict the probability that a company will go into bankruptcy (e.g., the Altman score); ii) the information acquired during the interactions between the bank and the company, which therefore constitutes private information for the bank. Depending on the importance given by a bank to one or the other type of information, one refers to transactional or relational banking operations.

The accumulation of private information which characterises relational operations confers an informational rent on the bank in possession of this information. In essence, there is no market for this information. It can thus be exploited by the bank in order to set lending conditions to its advantage vis-à-vis the related company that finds itself captive; in economic literature, this condition is known as a hold-up situation (see for example the theoretical developments of Sharpe 1990 and Rajan 1992). In the case of multi-bank companies, some banks will prefer to delegate their credit analysis function to those with privileged information (a free riding situation described by Carletti et al. 2007).

In this context, credit rating agencies play a leading role as providers of information and help to partially address information asymmetry problems. Cahn, Girotti and Salvadè (2018) illustrate this point by analysing the reform of the Banque de France company rating methodology, which took place in 2004.

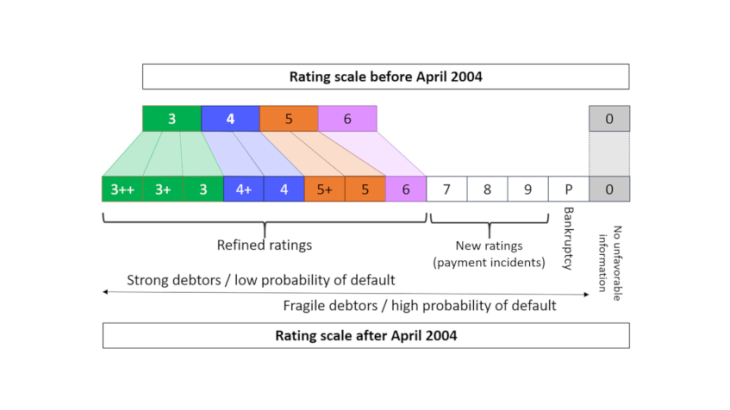

The Banque de France rating and the methodological reform of 2004

By assigning a rating to non-financial corporations, the Banque de France supports the implementation of monetary policy and the measures aimed at maintaining financial stability. Monetary and financial institutions can refinance themselves with the Eurosystem by pledging their claims held against companies, provided that the latter have a sufficiently high rating. In addition, this rating can be used by credit institutions to assess the robustness of their loan portfolio, in particular when calculating regulatory capital requirements (see Schirmer 2014 for more information on ratings and their use).

Credit risk analysis is characterised by a rating, which corresponds to a level on a rating scale. The Banque de France assigns this rating free of charge to companies whose turnover exceeds EUR 750,000. This rating, together with almost all of the underlying financial information, is then disclosed to the banking sector through the FIBEN company database.

Up until April 2004, the rating scale had four levels. The Banque de France then fine-tuned this scale by creating intermediate classes and supplementing it with additional levels (see diagram). This reform mainly resulted in the introduction of additional thresholds applicable to certain financial ratios. These thresholds enable companies to be broken down within a same class. Thus, while the underlying financial information remained unchanged, the ratings of some companies increased (for example from 3 to 3++ or 3+), while those of others remained stable (3 to 3). In economic jargon, this methodological change constitutes a "natural experiment" which can be exploited to identify the effect of the rating on the supply of credit to firms.