The role of labour market characteristics for inflation dynamics

Characteristics of wage negotiations in labour markets influence how economic shocks on the supply and demand side affect the economy. If collective bargaining institutions are set-up such that they internalize the economy-wide effects of wage adjustments, e.g. via unemployment, collective bargaining is likely to be more muted after a transitory rise in inflation. However, if feedback effects arising from wage negotiation outcomes on the rest of the economy are mostly ignored, unions may negotiate higher wages, leading to more persistent inflation dynamics (Bowdler & Nunziata 2007). A special case is wage indexation to prices as it introduces a structural backward looking component into nominal wage contracts (Fuhrer 2011).

These labour market characteristics have hence implications for the shape of the so-called wage Philips curve relationship, which describes the link between current wages on one side and past wages and unemployment on the other side. The main take-away is that under wage indexation inflation is more sensitive to unemployment, making the wage Phillips curve ‘steeper’ as the business cycle matters more for wage setting (Gali 2011).

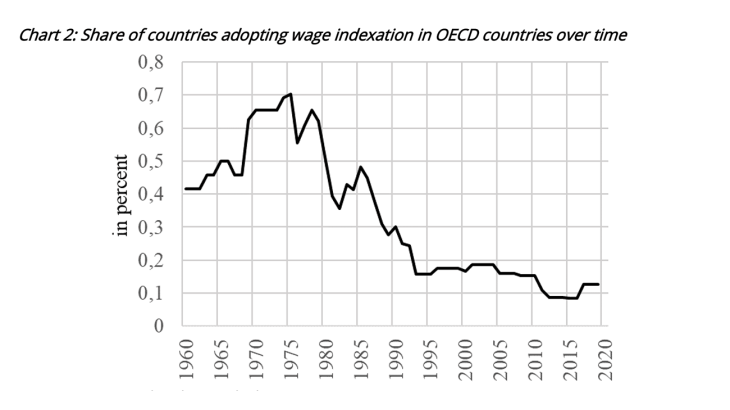

Wage indexation over time and across countries

Chart 2 depicts the prevalence of wage indexation in 56 countries of the European Union and the OECD since 1960, i.e. the share of countries in which collective agreements contain some clause linking wages to prices. This was for instance the case in France before 1983 (except in 1968 and 1976). While the share of countries with wage indexation increases at the beginning of the period, chart 2 reveals that this trend is reversed in the late 70’s. This is consistent with policymakers trying to weaken the price-wage loop in order to contain the inflationary consequences of the oil shock of 1973. In 2020, the share of countries with wage indexation is approximately 10%, which is four times smaller than in 1960. Five out of six countries with wage indexation in the sample in 2020, however, are located in the European Union (notably BE, BG, CY, LU and MT).

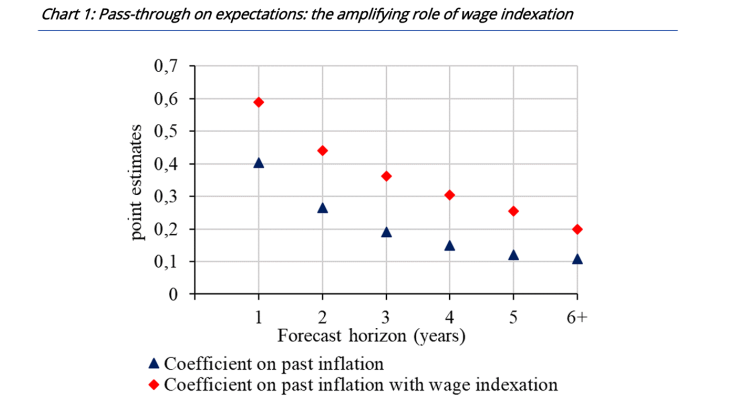

Wage indexation leads to less well anchored inflation expectations

Wage bargaining involve employers and households. Unfortunately, data on inflation expectations for firms and households across a large number of countries and going back in time is not readily available, although some progress is underway (Bouche et al. 2022). We therefore refer to inflation expectations by professional forecasters, which are known to affect household and firm inflation expectations since they are widely publicized (Carroll 2003). Professional forecasters base their assessment of the inflation outlook on models that are calibrated using historical data, which, inter alia, reflect the institutional features prevailing in the economy. Inflation forecasts for countries that exhibit a larger fraction of automatic indexation of nominal wages to inflation should therefore imply a higher pass-through of current inflation on short- to medium-term inflation expectations via this inflation-persistence channel. However, if inflation expectations are well anchored, this effect should dissipate with the forecast horizon. Long-run inflation expectations should be unaffected in this case by the amount of inflation persistence in the short-to-medium-term, as monetary policy is believed to bring inflation back on target over the medium term. On the contrary, if inflation expectations are not well anchored, a temporary shock in inflation will start the price-wage loop, leading to a shift in long-term inflation expectations, extending the short-to-medium-term effect.