Following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the concept of Finance-Neutral Output Gaps (FNOG) has gained widespread attention among policymakers. Borio et al. (2013) presented this concept as a substitute to the conventional concept of inflation-neutral output gap given the possibility that the economy overheats even if price inflation is low, if financial or external imbalances are building up. Introducing financial variables into the output gap estimations may yield to complementary tools for policymakers to avoid diagnosis errors associated with financial booms.

The concept of potential growth and output gap is most often based on the absence of inflationary or disinflationary pressures. However, several factors can lead to a disconnect between price inflation and financial asset prices. Frequently, financial booms coincide with positive supply-side shocks, leading to a drop in prices (lowering inflation). Concurrently, upswings in financial markets lead to an increase in valuations of real assets that in turn reduce financing and supply constraints (collateral effect). Furthermore, buoyant financial markets may sometimes lead to an appreciation of the domestic currency, resulting in lower consumer prices through the import price channel. Finally, accommodative financing conditions may not only spur demand in the short run, but also have persistent effects on the supply side through labour, productivity, or capital accumulation (reverse hysteresis effect), weakening further supply constraints and prices.

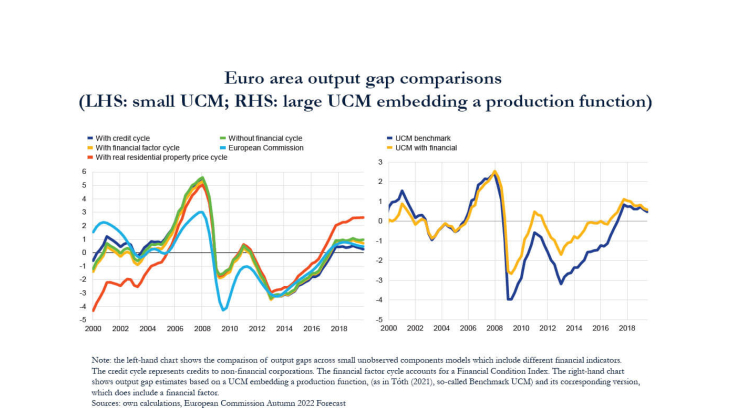

The idea behind this paper is to construct output gaps and potential output measures for the euro area underpinned by both macroeconomic relationships and financial variables. For this, we follow two approaches. On the one hand, we include financial information in small Unobserved Components Models (UCM) commonly used to assess FNOG (Figure A, left-hand panel). On the other hand, and this constitutes a novelty of this paper, we elaborate on a richer Unobserved Components Model embedding a production function, as in Tóth (2021) in which we include financial factors (Figure A, right-hand panel).

This exercise is challenging for at least four reasons. First, the resulting output gaps should track the current narrative on macroeconomic cycles and trends, especially the labour market trends as they are provided in the UCM. Second, we should improve (or at least not worsen) the real time performance of the model. Third, in a central banking context we would like to estimate output gaps with good forecasting ability. Finally, we have to select appropriate financial variables out of a large set of variables, stemming from different sources (national accounts, private providers, etc.).

Results from the literature usually show that Finance-Neutral Output Gaps differ substantially from traditional gaps, especially around financial crises. This is also what our work will highlight and in that respect, the choice of the financial variables matters somewhat (Figure A, left-hand panel). In a UCM embedding a production function, the FNOG points to stronger tightness in goods and services markets over the decade following the Global Financial Crisis (Figure A, right-hand panel). This, in turn, suggests that potential output in the euro area may have suffered more from the effects of the GFC when we account for financial factors in estimating potential output, compared to modelling that disregards these factors.