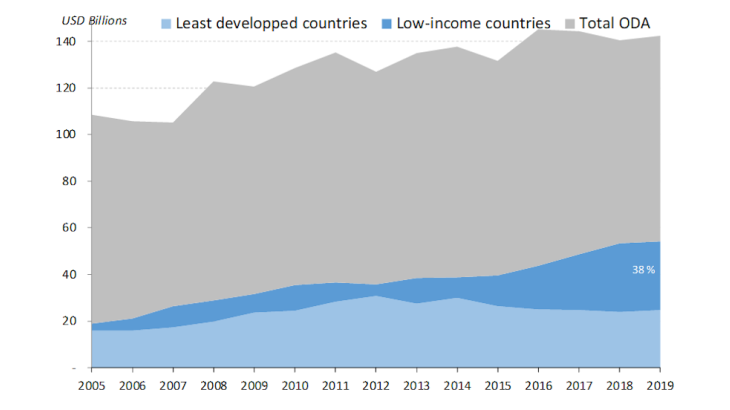

Although low-income countries (LICs) have so far been less directly affected than developed countries by Covid-19, the pandemic could still have major economic and human consequences for LICs due to their extreme vulnerability. According to the IMF, in 2020, these countries will have to face up to a 1% contraction in GDP, a rapid widening of their budget deficit (2 percentage points of GDP higher than in 2019 and even 7 percentage points higher for oil-producing countries) and significantly elevated public debt (up 5 percentage points to 49% of GDP). The financing needs of LICs are expected to be even more substantial given that they have limited tax resources (16% of GDP on average) and high levels of debt (more than 50% are at high risk of debt distress according to the IMF’s classification).

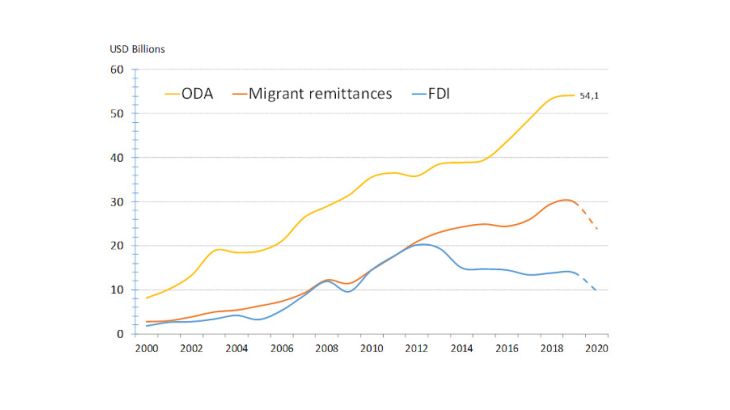

Changes in ODA (government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries) in 2020-21 represent a major financial concern for LICs. ODA is their most significant source of external financing (more than USD 54 billion in 2019): twice the value of migrant remittances and four times greater than the amount of foreign direct investment (see Chart 1). And at a time when these latter financing sources are expected to decline dramatically, ODA plays a crucial countercyclical role in reducing imbalances caused by the shutdown in activity.

Multilateral aid should increase in response to the crisis

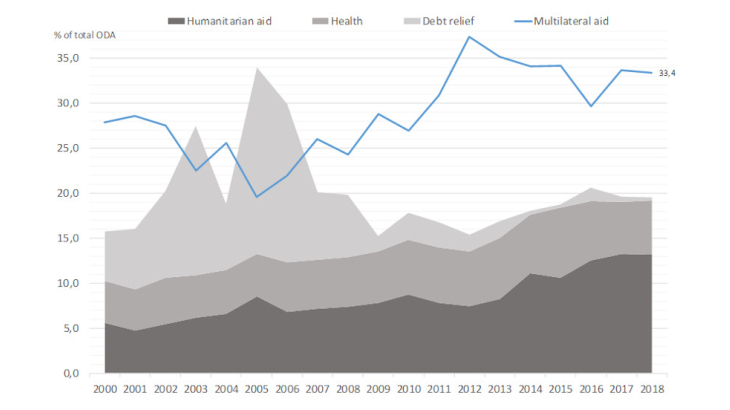

This crisis should result in a surge in ODA thanks to rapid and extensive support to LICs from multilateral institutions (multilateral aid accounted for one third of total ODA in 2019 – see Chart 2). The IMF has implemented an emergency zero-interest facility financed through its Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) and accompanied by commitments from multilateral banks. In conjunction with this financing, a debt service suspension offering relief to 73 eligible countries (39 of which had declared their interest as of 9 July 2020) during the period from 31 May 2020 to 31 December 2020 was adopted under the aegis of the G20. This initiative may be carried over into 2021, conditional on the pandemic’s evolution.

Depending on the scale of the crisis in LICs, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa, additional aid, notably to support health systems, as well as debt rescheduling or forgiveness, may be needed. The involvement of private lenders in these types of initiatives would be welcome in order to prevent individualistic behaviour or “holdouts” (particularly debt repurchases by vulture funds) and to better share costs between public and private creditors. The main donor countries of official development assistance recently agreed on a better method for reporting debt relief or forgiveness in order to encourage such efforts.