State aid is prohibited by EU law (Article 107 TFEU), with some exceptions, as it is deemed contrary to the free competition principles of the internal market. For example, in 2018, the European Court of Justice ruled that state aid granted by the Belgian government to Ryanair was illegal.

However, according to Article 107 TFEU, this framework may be eased in the event of “exceptional occurrences” or "serious disturbances" to the economy. As early as 19 March in the context of the Covid-19 crisis, the Commission defined a Temporary Framework for State aid measures to enable EU countries to support their companies in difficulty as a result of this crisis, by granting, by end-2020 and for a limited period of time, subsidies, State-guaranteed loans (SGL) and soft loans. It then extended this framework on 3 April, 8 May and 29 June to cover aid for disease control, recapitalisation (possible until mid-2021) and start-ups.

This aid has helped to support sectors that would not have been supported in the absence of a crisis, such as aviation. This framework has been widely used: according to the Commission the amount of authorised State aid, mostly in the form of SGLs and soft loans, amounted to over EUR 2,190 billion at the beginning of June 2020.

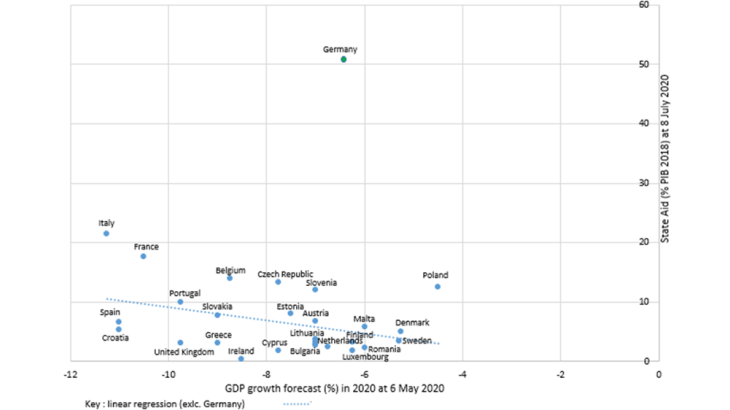

The scale of the crisis called for a rapid response. However, the idea that the most affected economies were also those that had received the most State aid was not entirely borne out in reality.

Heterogeneous distribution of State aid

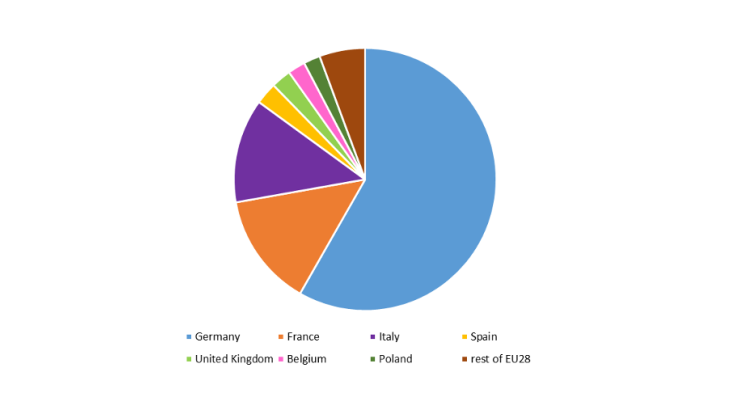

In terms of amount, authorised State aid until July 2020 concerns first and foremost the major economies: Germany (58% of the total), France (14%) and Italy (13%) (Chart 1).

It should be noted that for Germany, and to a lesser extent Italy, these are Commission estimates because several State aid measures granted by these countries do not specify an amount, particularly those in the form of SGLs. The budgeted measures correspond to ceilings, and are not de facto necessarily used to their full amount.

In addition, only roughly EUR 338 billion are allocated to specific sectors, in particular disease control (medical equipment, R&D) and sectors where most of the activities cannot be carried out by teleworking (e.g. transport). The other measures are less targeted, sometimes concerning companies in difficulty of a specific size (e.g. SMEs) or companies in difficulty of various sizes and sectors.

Why are there such differences between Member States? According to what rules is State aid granted?

A European framework for nationally funded aid

State aid is authorised by the Commission. It checks that the aid complies with the conditions laid down in the Temporary Framework and the TFEU, both in terms of the time horizon and the financial viability of the beneficiary companies, which should not have been in difficulty on 31 December 2019.

State aid is financed at national level, which tends to favour countries with greater budgetary room for manoeuvre. This could explain the significance of German State aid (as a percentage of GDP), even though Germany is not the EU country most affected from a health and economic standpoint (Chart 2).

However, the introduction of State aid does not mean that it is consumed quickly or entirely. This makes comparisons more difficult and calls for qualifying the amount of German State aid, which is mainly composed of SGLs and soft loans. Anderson et Al. (Bruegel, 2020) have put forward an analysis of the actual use of SGLs: the amount of State guaranteed loans committed in Germany at end-June 2020 is estimated at around 1% of GDP in Germany, i.e. below the Italian (2.2%), French (4.4%) and Spanish (6.2%) levels. While the difference between the amounts announced and committed so far seems to strongly limit the distorting effect on the internal market, it is advisable to remain cautious at this stage, as this risk remains.